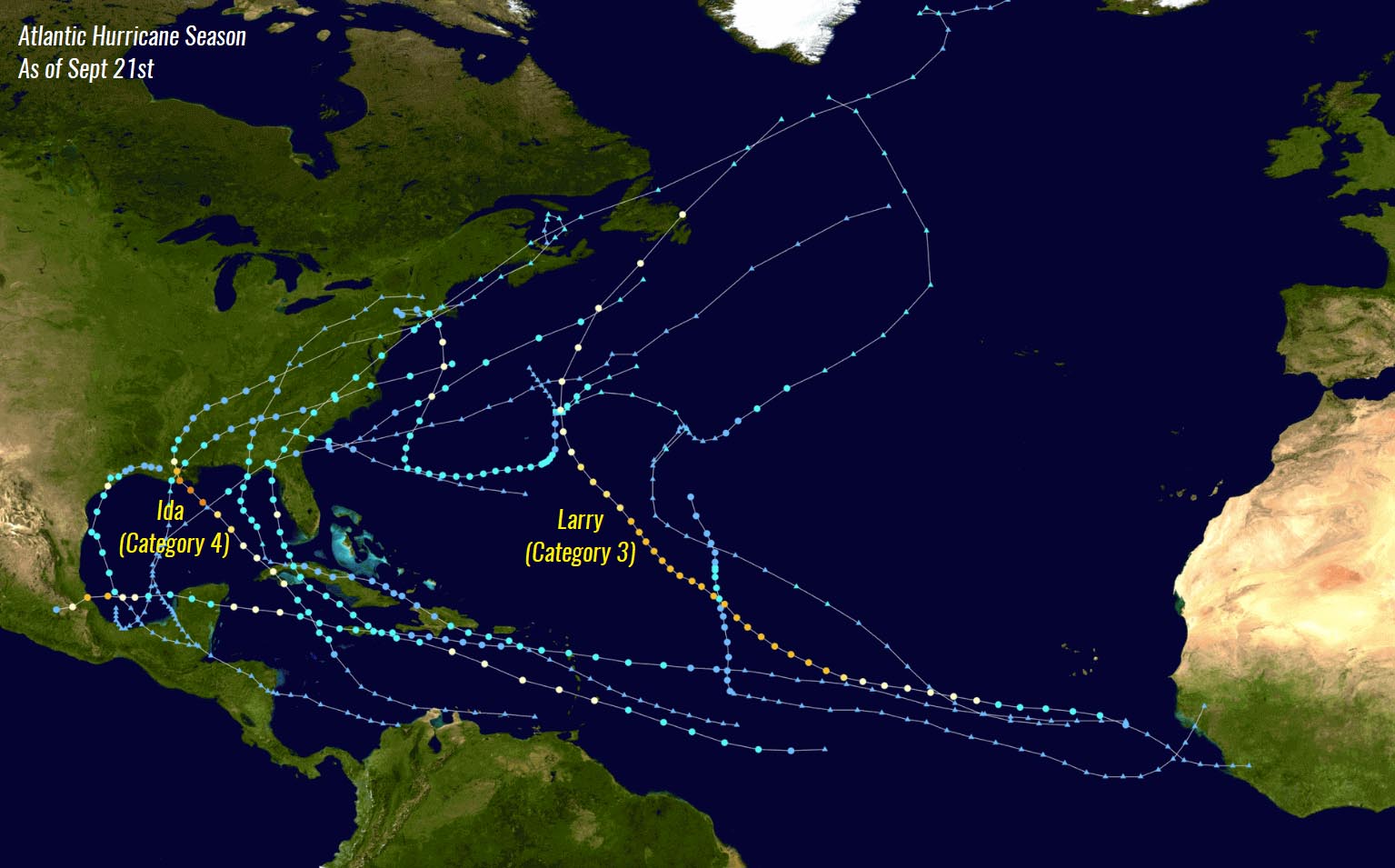

The Atlantic Hurricane Season 2021 has literally escalated in the activity recently, as 12 named tropical storms, including 5 hurricanes formed in the last 40 days. That is more than the average number of named storms in one full season. Going into late September and October, the activity is gradually shifting to the Caribbean region and will soon be boosted by the incoming major MJO wave. We might even need a supplementary list of storms again.

IMPORTANT UPDATE: Sam Forms, Forecast to Become the Next Major Storm of the Atlantic Hurricane Season 2021 as it Heads Towards the Caribbean by Sunday and Next Week

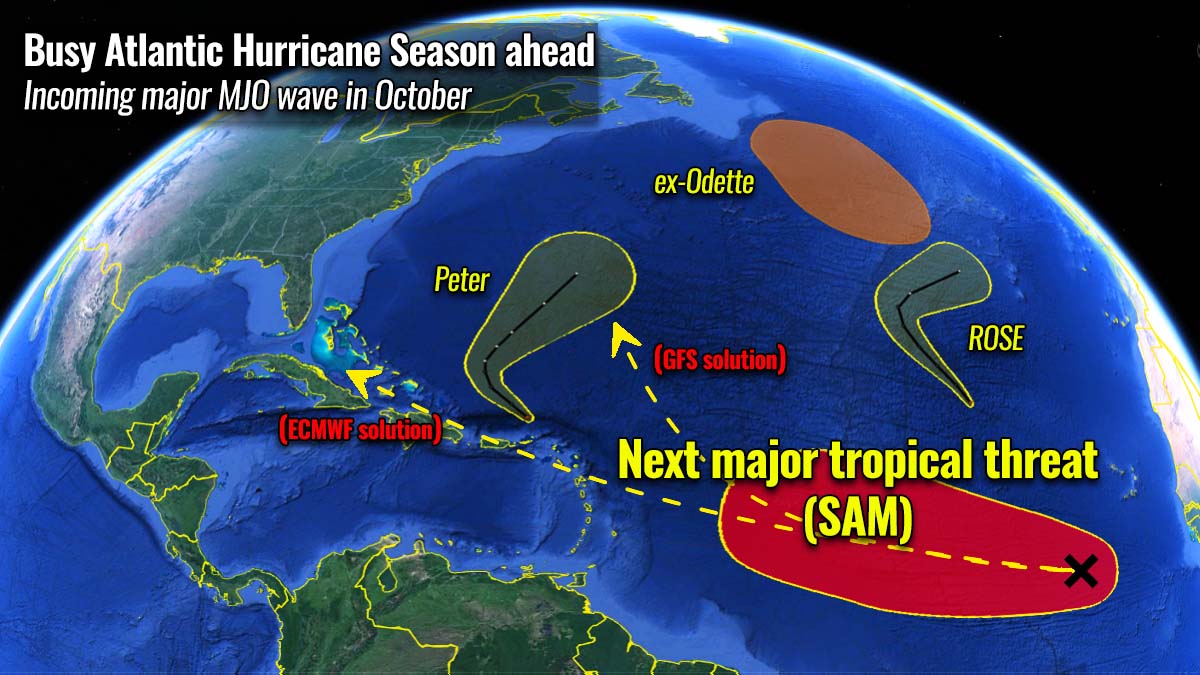

As of today, Sept 21st, a start of the meteorological fall, the Atlantic Hurricane Season runs at 17 named tropical systems, about 75 % above the normal activity. Tropical Storms Peter and Rose have been ongoing in the central Atlantic and another, potentially major, 18th named storm will soon follow. The next name on the 2021 tropical cyclone list is Sam.

Only one Atlantic hurricane season has had more than 18 named storms by September 26th, that was 2020. Does it hint at anything?

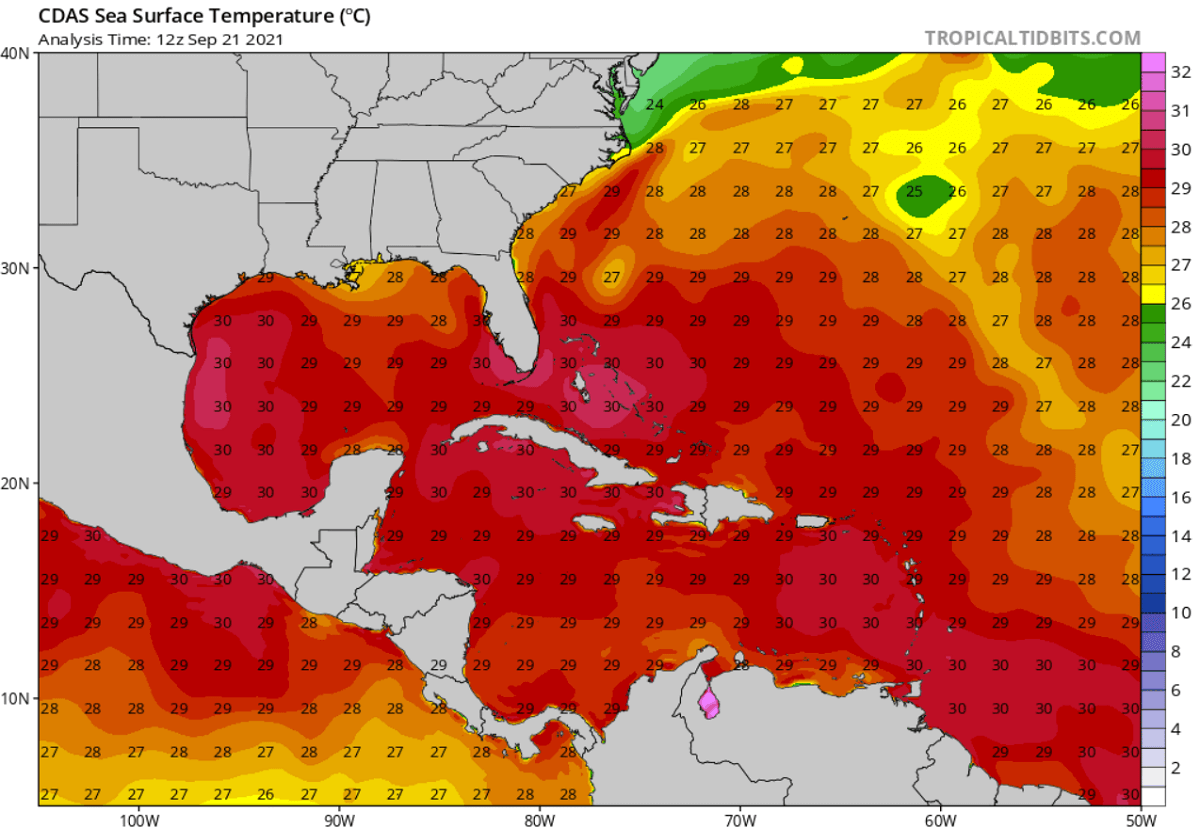

The recent significant tropical activity in the Atlantic basin has pushed the statistics into the territory the 2005 and 2020 were charting. And this is concerning, a lot. Especially as we are seeing a tremendous amount of hot oceanic water remaining in place and will soon be coinciding with a major MJO wave emerging from the west.

The ongoing storms will soon get company, as forecast parameters will likely trigger more tropical storms and boosting the already hyperactive Atlantic Hurricane Season.

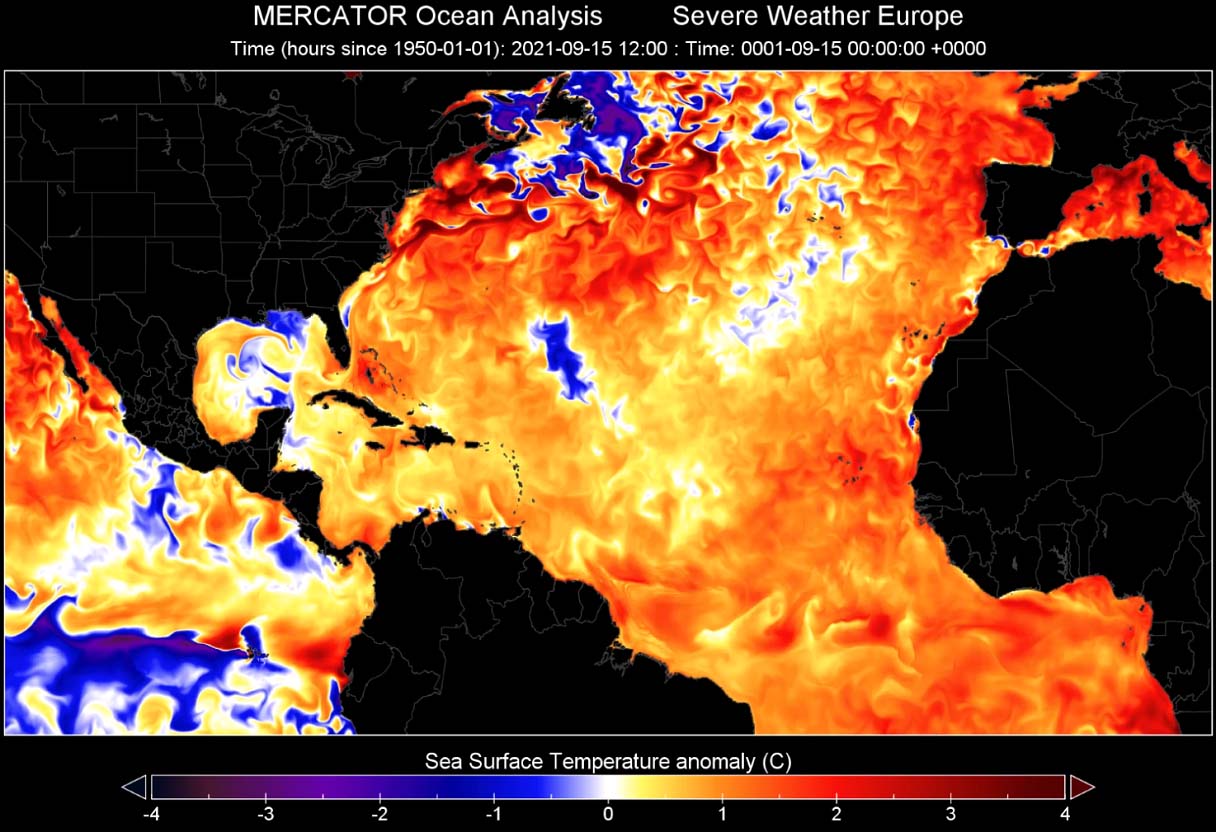

We have prepared a high-resolution animation below, revealing how the Atlantic Basin oceanic waters are anomalously warm. These anomalies do hint at the prolific environment for a very busy period coming up as we head into the final two months of the Atlantic Hurricane Season 2021.

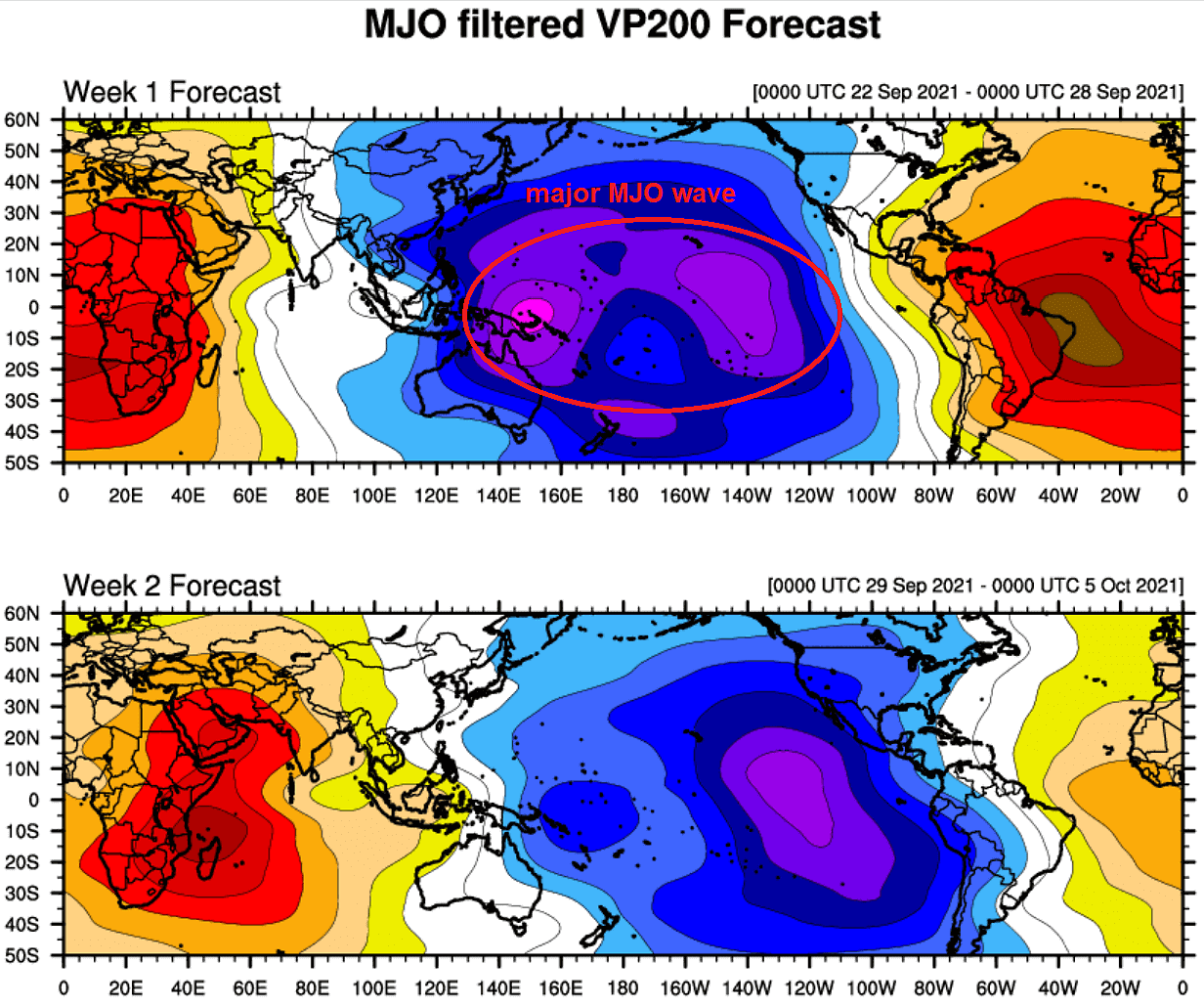

With the emerging MJO wave aloft, we are seeing strong support for potentially even higher tropical cyclone development in the coming weeks. A deep atmospheric wave that is currently over the Pacific Basin, will soon emerge into the Caribbean region and the tropical Atlantic.

POTENTIALLY DANGEROUS PERIOD AHEAD AS A DEEP MJO WAVE INCOMING

Let us first provide some basics about the MJO, what is it and why is it an important large-scale feature for the activity during the Atlantic Hurricane Season?

The general weather activity across the tropical region is quite different from the mid-latitudes or the polar region. The latter have cold and warm fronts, while the tropics do not have such activity. But the weather mostly combines a convective weather activity (thunderstorms) within the large-scale pressure and wind patterns variability. And a lot of the tropical dynamics are driven by ‘invisible’ wave-like features in the atmosphere.

The Madden-Julian Oscillation, or short MJO wave, is the largest and the most dominant source of short-term activity in the tropical region. The MJO wave is an eastward moving disturbance of thunderstorms, and it circles the Earth in the equatorial region in about 30 to 60 days. MJO has two parts: an enhanced rainfall (wet phase) on one side and the suppressed rainfall (dry phase) on the other side.

Note that the horizontal movement of air is referred to as the Velocity Potential (VP) n the tropical region. This is an indicator of the large-scale divergent flow in the upper levels of the atmosphere over the tropical region. The blue colors strongly support tropical development, while the red colors are the opposite, usually suppressing the activity.

The chart above, provided by Michael J. Ventrice, reveals the current MJO wave stage with filtered VP anomalies. A major MJO wave is moving east across the Pacific Ocean, entering the Caribbean region and western Tropical Atlantic by early October.

The ongoing activity and especially the next potential tropical cyclones forming in the final two months of the Atlantic Hurricane Season (we believe Sam could be the next major storm) will gain strong support by these improving upper-level conditions coming up.

As we learned, the Madden-Julian Oscillation is a very important factor for cyclone formation in the tropical region. When a region is being overspread by a major MJO wave, it normally leads to a low wind shear environment and results in more favorable conditions for tropical cyclone development and hurricane activity.

MAJOR TROPICAL ATLANTIC WATER TEMPERATURE ANOMALY

The Atlantic Basin water surface temperatures (SST) have warmed up a lot throughout the first four months of the hurricane season this year, with areas of surface seawater temperatures rising into the low 30s °C. The recent temperature anomaly analysis indicates that the whole Atlantic Basin actually has anomalously warm waters, even extreme in places. That includes the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and most of the tropical and even the North Atlantic waters.

The warmest sea waters are spread around the Lesser Antilles, the Bahamas, around Cuba and Florida, and most of the Gulf of Mexico. Temperatures in these areas are ranging from around 29 to 31 °C, being just a tad lower elsewhere in the Atlantic Basin. These are extremely warm for mid/late September and are forecast to remain in a similar range also into October.

Seawater temperatures this high often lead to very rapid the explosive development of dangerous tropical cyclones during the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season and also in the fall months. Anomalously high water warmth is a very significant signal for any of the upcoming tropical cyclones that would graze into this part of the tropical region. The convective storms associated with this system will fuel by these conditions and intensify the cyclones.

The SSTs have been anomalously warm this hurricane season, especially across the MDR region (Main Development Region). A part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean extending between Africa and the Caribbean Sea where the majority of the tropical cyclone formations normally occur, and track towards the Caribbean and the United States.

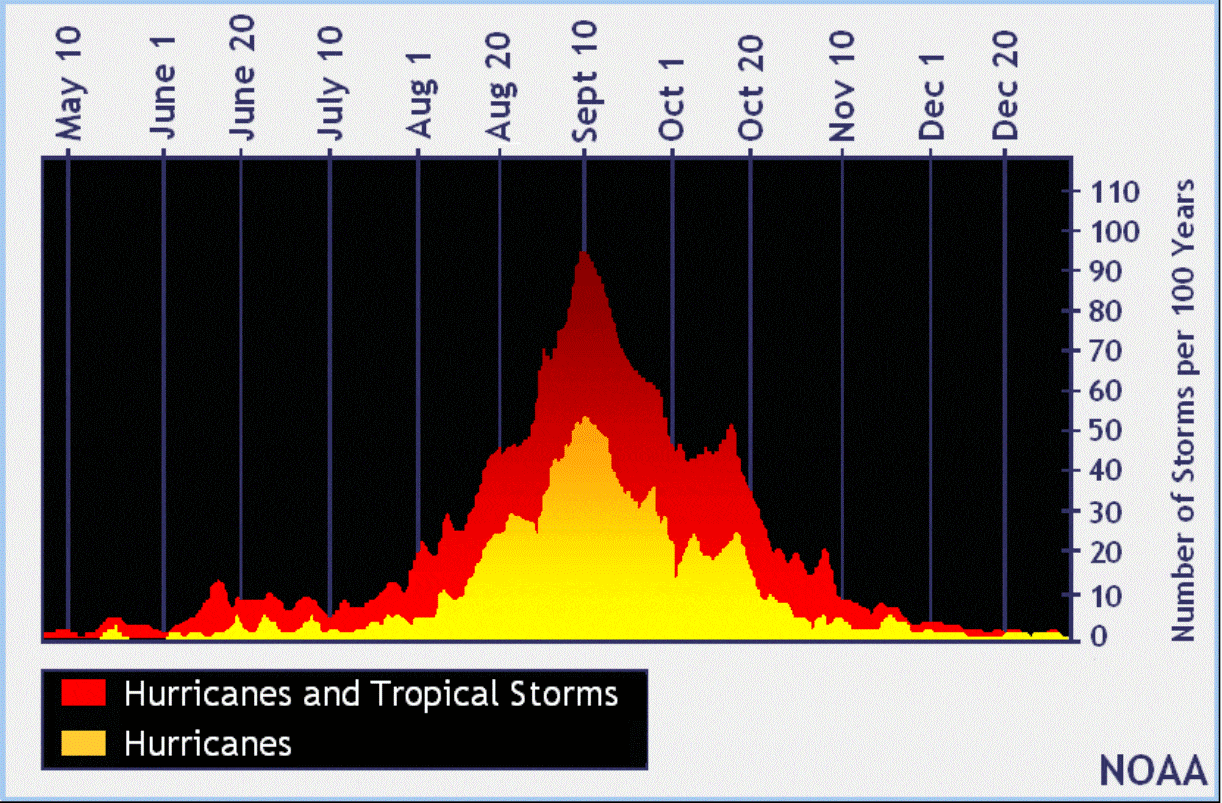

ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON PAST ITS STATISTICAL PEAK, RUNNING AT 75% ABOVE AVERAGE

September 10th was the official long-term statistical peak of the Atlantic Hurricane Season. As of Sept 21st, there have been 17 named storms, which is about 75 % of the average amount of named tropical cyclones in a typical year. The currently active storms are Peter, Rose and both will soon get the company as Sam, the 18th named storm of the Atlantic Hurricane Season 2021, is in sight late this week.

As we can see, the 2021 hurricane season is actually well ahead of the schedule. Through Sept 21st, there are normally about 10 named storms, 4.5 hurricanes, and two major hurricanes. While we have already seen 6 hurricanes and also 3 major hurricanes (Grace, Larry, and Ida). Hurricane statistics are running at 33-50 % above normal as of this date.

The below graphics, provided by dr. Philip Klotzbach, reveals that all the parameters that we are usually looking at during the Atlantic hurricane season are significantly above average. We are seeing well-above-average named storm days and indeed cyclones, hurricanes, and major hurricane days.

According to the analysis by Sam Lillo, the trajectory of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season statistics look really similar to the 2005 and 2020 surges in named storms. And we can remember both of those years had the highest number of named tropical cyclones in history, 2020 had 30 storms, while 2005 had 28 storms. We can also see the nearly one month break in the activity during July this year.

But just take a look at how steep an increase is the 2021 graph (stars mark each of the named systems), particularly in the recent weeks. The Atlantic hurricane season activity has really ramped up since early August.

ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON COULD RAN OUT OF ITS NAMES – WHAT’S NEXT?

We could soon be entering uncharted territory with this year’s Atlantic hurricane season names. For the second year in a row. La Nina might be to blame, but the statistics and the forecasts for the upcoming weeks are nothing less than obvious.

The recent hyperactive period in the tropical Atlantic, and considering we have extremely warm sea waters and the incoming major atmospheric MJO wave coming up, undoubtedly makes it very likely that we will be beyond the full list of 21 tropical cyclone names next month.

Those four names that remain on the list are Sam, Teresa, Victor, and Wanda. Note that none of them has even been used in Atlantic tropical history. Then, we are off to the supplementary list of storms. A list that is predetermined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). These new supplementary names will be given additional more friendly named storms, rather than using Greek alphabet letters as we had in the most active years so far, the 2020 and 2005 hurricane seasons.

With 17 named storms under the season’s belt by Sept 21st already, there is still more than 40 % of the official hurricane season to go, that’s more than two months. We already have seen 6 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes this year.

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season keeps setting statistical records and is following the early seasonal prediction that were hinting at a very active year in the tropics. The recent forecast updates call for possibly 7-10 more storms by the end of the season, officially ending by November 30th.

There could be about 5 more hurricanes, including two of a major, Category 3 or greater intensity. Also, two or three more storms could impact the United States mainland until the season is finally over.

Above: Geocolor satellite scan of major hurricane Ida prior to its landfall in Louisiana. Image by NOAA

ACCUMULATED CYCLONE ENERGY COULD CHALLENGE ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON 2020

We are collecting the tropical systems so fast this year, that we are really not far behind the record-breaking hurricane season 2020. But the number of storms is not all, we also use a so-called ACE index, a metric that is used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. With these metrics, we can then compare every tropical storm or hurricane with the other.

ACE in an abbreviation for the Accumulated Cyclone Energy.

As of Sept 21st, more than 82 ACE has been accumulated by all the 17 named tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Hurricane Season 2021. The highest ACE was collected by the recent major and long-lived hurricane Larry, 32.8 ACE after 11 days of the system being alive in the Atlantic.

This is three times more than Major hurricane Ida (10.8 ACE), hurricane Elsa (9.5 ACE), and hurricane Grace (9.1 ACE). And indeed more than all those three hurricanes together.

The Atlantic hurricane season last year, for example, ended up at 185.8 ACE, quite well above the threshold for the ‘extremely active’ category which is 113. This placed 2020 into the Top-10 Atlantic hurricane seasons based on the Accumulated Cyclone Energy index.

Note, that the 2005 hurricane season, the one with the 2nd most named storms after 2020, ended up extremely high – its final ACE was 250.

The chart above indicates the recent 15 Atlantic hurricane seasons by ACE records with the related number of hurricanes in that particular year.

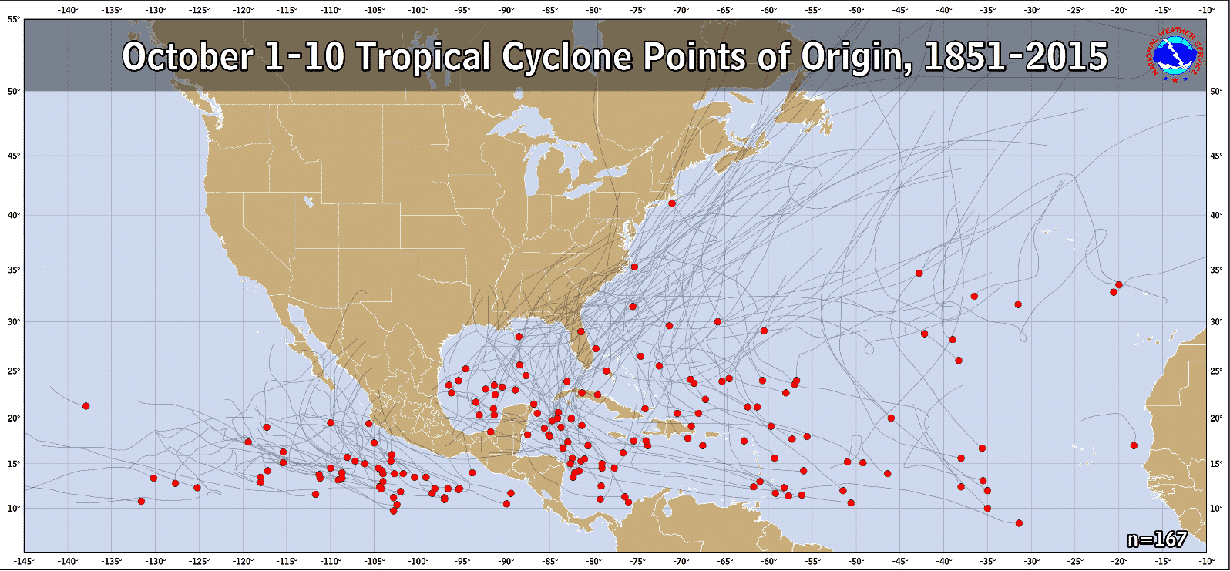

OCTOBER COULD BE A EXTREMELY BUSY MONTH IN THIS YEARS’S ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON

With the statistical peak of the Atlantic Hurricane Season occurring around September 10th, the month of October is normally a bit less active. But this year could potentially be quite different, especially if we are aware of the major and deep MJO wave incoming into the Caribbean region and the tropical Atlantic soon as September is over.

The attached NOAA graphics below indicate the storm frequency throughout the typical Atlantic Hurricane Season, with obvious peak activity in early September but also October’s secondary ‘peak’. This is indeed an average graph for the number of storms in 100 years, but both peaks are pretty eye-catching.

What is particularly important to pinpoint are different areas that are typically affected during the late hurricane season. The main change in regard to the geographic activity from September to October is the shift of the activity closer to the United States mainland. The typical tropical storm development areas in October hint that the majority of the tropical cyclones develop in the western tropical Atlantic.

Once we enter October, the African easterly wave gradually weakens and diminishes, so the Caribbean region takes over as the main source region of storms. And the secondary peak often develops destructive hurricanes in the Caribbean region that turn towards the Gulf of Mexico. Let’s just remember how powerful and destructive were hurricanes Delta, Epsilon and hurricane Zeta occurring in October during the 2020’s Atlantic hurricane season.

As the general, late hurricane season weather patterns in October shift the storm trajectories from the western tropical Atlantic towards the north and then northeast, the potential for the landfall of tropical cyclones and hurricanes also increases for Florida and the U.S. East Coast.

Attached below is the historic occurrence of tropical storms and hurricanes throughout the month of October. The Caribbean region, the eastern Gulf of Mexico, the Florida Peninsula, and the East Coast have the highest frequency of storms. The prevailing tracks are marked with white arrows.

Indeed there is still some tropical activity in the eastern and central Atlantic, but the main activity is generally shifting towards the western part of the Atlantic basin, as the eastern activity slowly vanishes throughout October.

One thing that is also in need to be considered is the re-developing La Nina recently.

The upper-ocean heat content (OHC) anomalies in the eastern and central tropical Pacific have dropped considerably in the past two weeks, hinting that the transition to La Nina begins shortly. It is combined with continued strong trade winds across the eastern and central tropical Pacific.

Typically, when La Nina conditions develop, the weather patterns extend the Atlantic hurricane season activity also later into fall due to reductions in vertical wind shear. And additional tropical cyclones are likely, even extending past the official end of the season which is set at November 30th.

BUSY TROPICAL ACTIVITY AS ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON HEADS FOR ITS SECONDARY PEAK

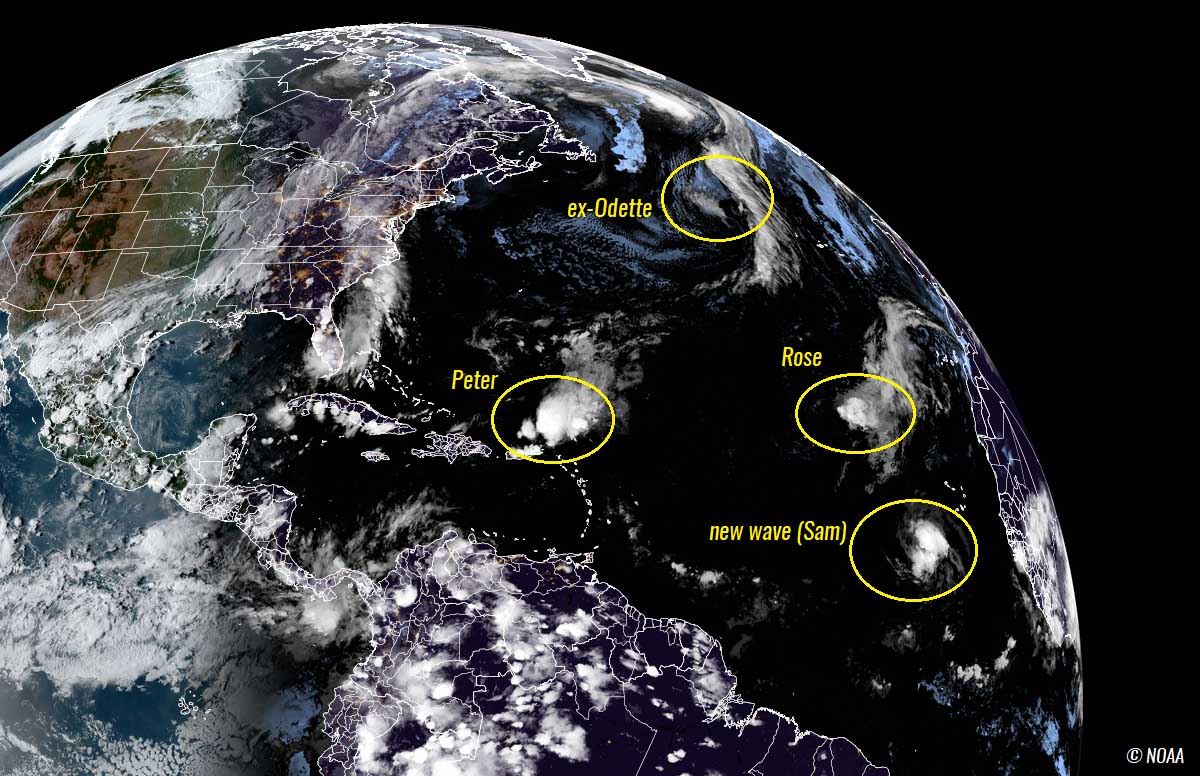

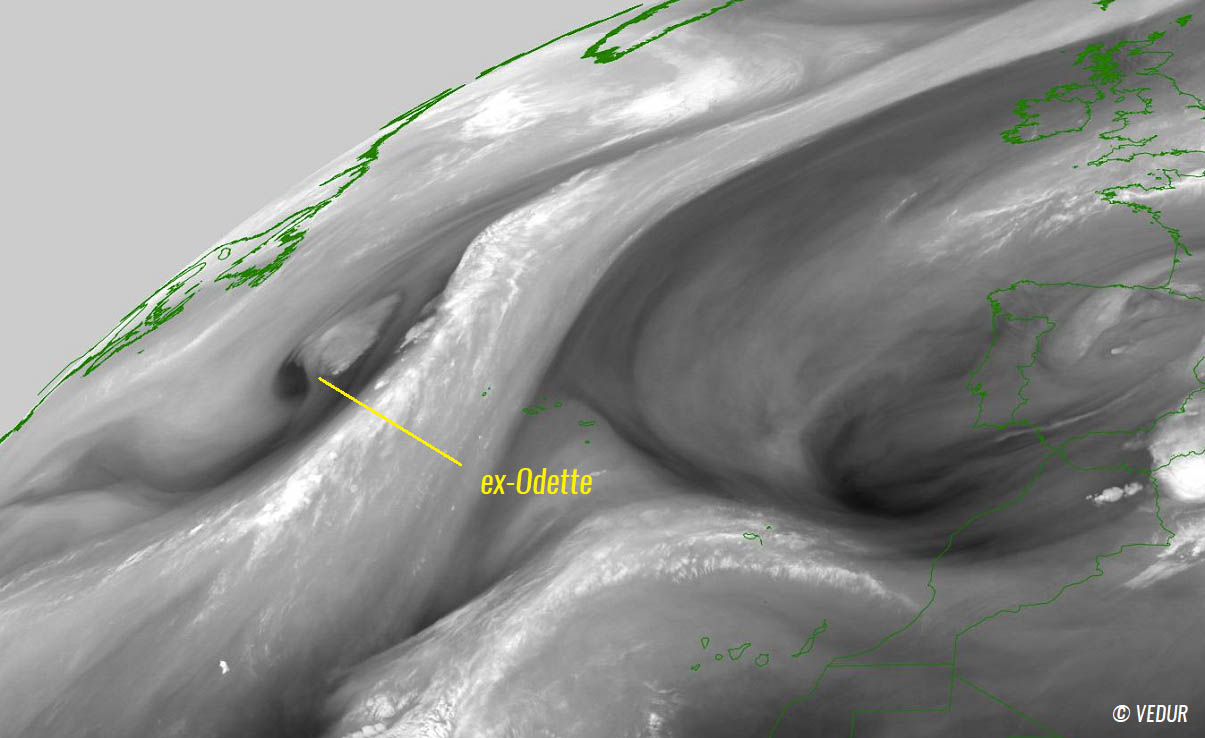

Soon after the major hurricane Larry grazing across the Atlantic in early September, tropical storm Mindy and hurricane Nicholas moves across the Gulf of Mexico, both having landfall in the United States landfall recently. They brought massive rain and floods along the Gulf Coast. Over the weekend, tropical storm Odette has formed near the Atlantic Coast and dissipated near Nova Scotia.

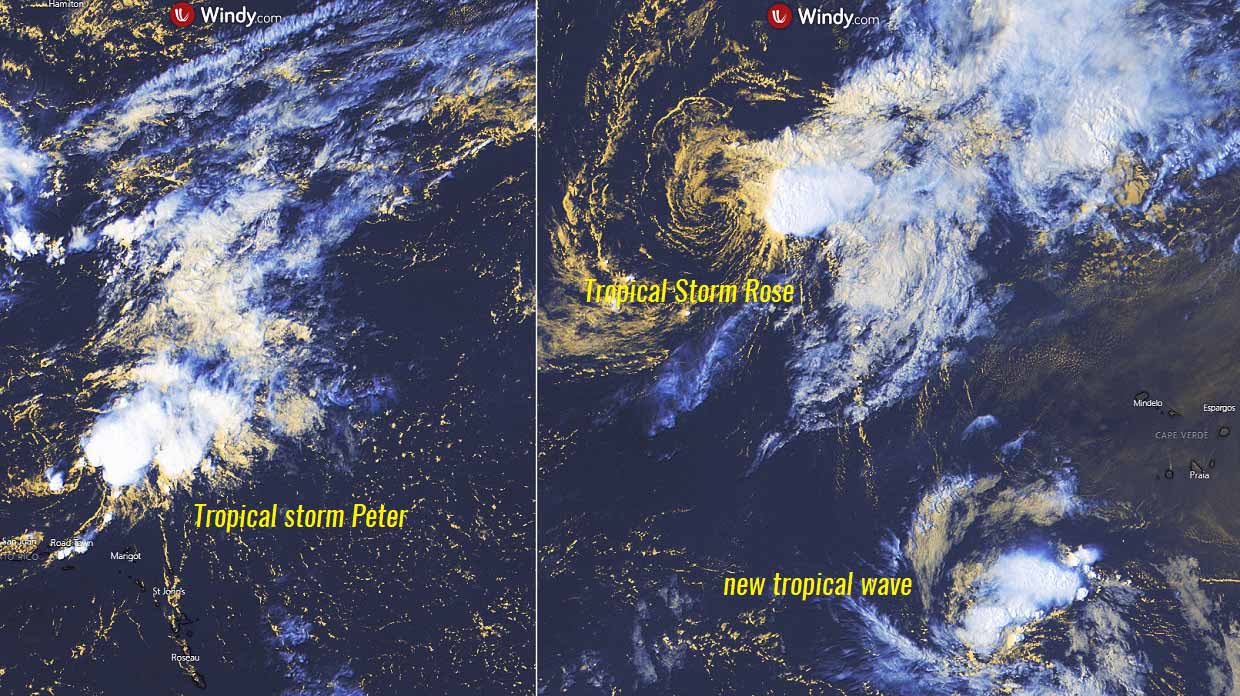

September took its statistical very active period pretty seriously, as Tropical Storm Peter and Rose formed in the central Atlantic. They both gained enough wind intensity to earn their names over the weekend. Peter formed about 600 miles east of the Leeward Islands while Rose was named soon after Peter while its initial tropical wave moving west about 400 miles west of the Cabo Verde Islands.

On Tuesday, Tropical Storm Peter was located about 150 miles north of Puerto Rico, moving to the west-northwest at about 10 mph, according to the NHC. Having its maximum sustained winds of around 40 mph.

Peter is unlikely to strengthen a lot since it is placed in a strongly sheared environment that is liming significant storm organization. Rose is also in a rather unfavorable environment, soon to become a tropical depression and gradually weaken further while drifting towards the northeast and dissipate before reaching the Azores.

But the tropical region farther south of the area where storms Peter and Rose are is hinting that a much more favorable environment is taking shape. And the region could soon produce another major tropical system, turning towards the Caribbean and the United States.

Another system to watch – Sam could be the next major Atlantic storm

A couple of hundred miles south of Tropical Storm Rose, another tropical wave has emerged off the African coast late Sunday and is expected to develop further later this week. This wave, which was designated as 98L by the NHC showed more organized, with a pronounced spin and an expanding area of heavy thunderstorms. It will be moving west at a lower latitude than Rose, giving it a potentially higher chance of entering the Caribbean region later.

Satellite imagery showed that 98L has a small but concentrated area of showers and thunderstorms that are re-developing along a tropical wave located a few hundred miles southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The environmental conditions are expected to become more conducive for development as the major MJO wave will gradually emerge from the west this week.

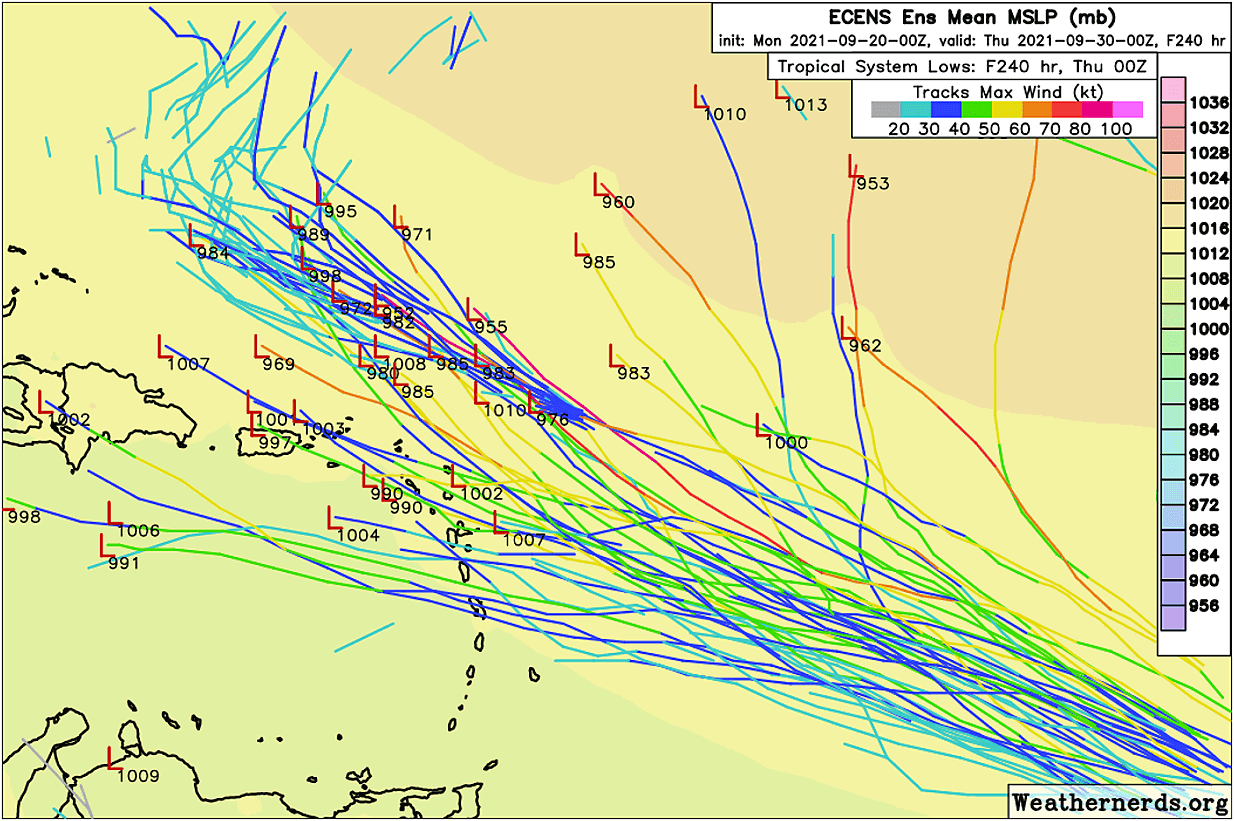

A tropical depression is likely to form by Thursday while the system will be moving westward at about 10 to 15 mph across the eastern and central tropical Atlantic Ocean. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) is giving this system a medium, 60 % chance to become a tropical depression through the next 48 hours. And a 90 % chance it becomes a tropical storm by the weekend. The next on the list is Sam.

Both the environmental and oceanic conditions are expected to remain favorable or further improve across the tropical Atlantic through the remainder of September. The extremely warm sea waters soon coincide with the major MJO wave aloft. So the close watching in the Antilles is advised, although the system is not going to be moving fast.

Attached below is the potential wind swath forecast by the ECMWF weather model solution, bringing (hurricane) Sam towards the Lesser Antilles early next week. However, it needs to be considered that the wave is still in the early developing stages, so significant differences in the track could occur. The potential three solutions have been marked with white arrows.

Option 3 takes a trajectory hinted at by the GFS weather model, while options 1 and 2 are leaning more towards the ECMWF model solution. Also, as we learned earlier, the statistical trajectories during the late Atlantic Hurricane Season activity give higher chances for the Caribbean. Indeed, the statistics are averaging data, so it just means higher probabilities are in place for the region.

We will continue closely monitoring the developing tropical storms and will be posing more updates in the coming days and weeks, stay tuned. Do make sure to bookmark our page and if you have seen this article in the Google App (Discover) feed, click the like button (♥) there to see more of our forecasts and our latest discussions on various weather topics.

** Images used in this article were provided by Windy, , and NOAA.