Australia – a land of fires and floods. This has been documented over the past several years with record-breaking fires during 2019/2020 spring and summer. By the 2020/2021 season, Australia was in the grip of the first of three La Niña events. A triple dip in La Niña is rare; it has only occurred twice since reliable records began in the 1950s, the first from 1973 – 1975 and again in 1998 – 2001.

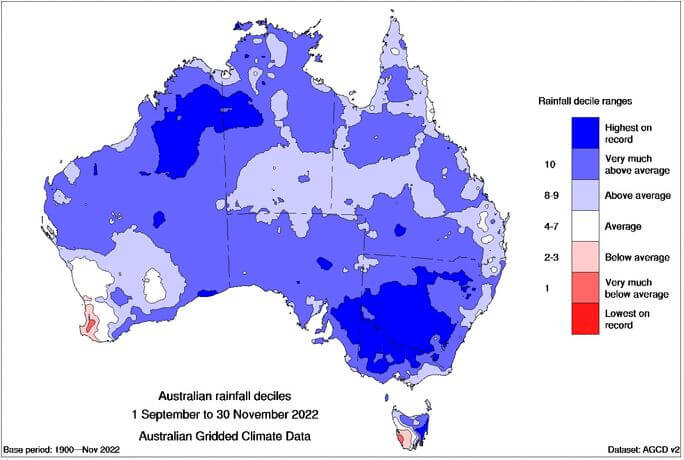

A third straight La Niña, in combination with a strong negative Indian Ocean Dipole and continued positive Southern Annual Mode, contributed to record-breaking rainfall across eastern Australia. Continued heavy rainfall led to Australia’s second-wettest Spring in history.

So, what are these phenomena that influence the weather so much?

WHAT IS ENSO, AND HOW DOES IT AFFECT AUSTRALIA?

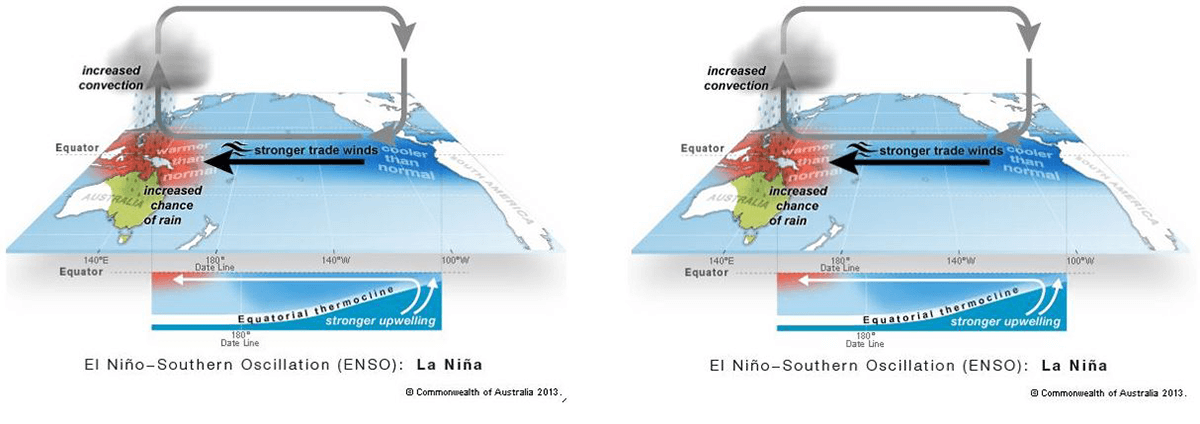

ENSO is a single climate phenomenon with three different phases. These phases are El Niño, La Niña, and a neutral phase. During and El Niño phase, sea surface temperatures (SST) in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean become warmer than average.

Usually, trade winds blow from east to west across the Pacific; however, during El Niño events, these winds weaken or even reverse. This results in drier conditions across Australia. Conversely, during a La Niña event, sea surface temperatures (SST) cool across the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean as equatorial trade winds become more vigorous.

Strengthening trade winds draw warmer waters across the Pacific towards northern Australia. This enhances the threat of heavy rainfall, flooding, and Tropical Cyclones for eastern Australia.

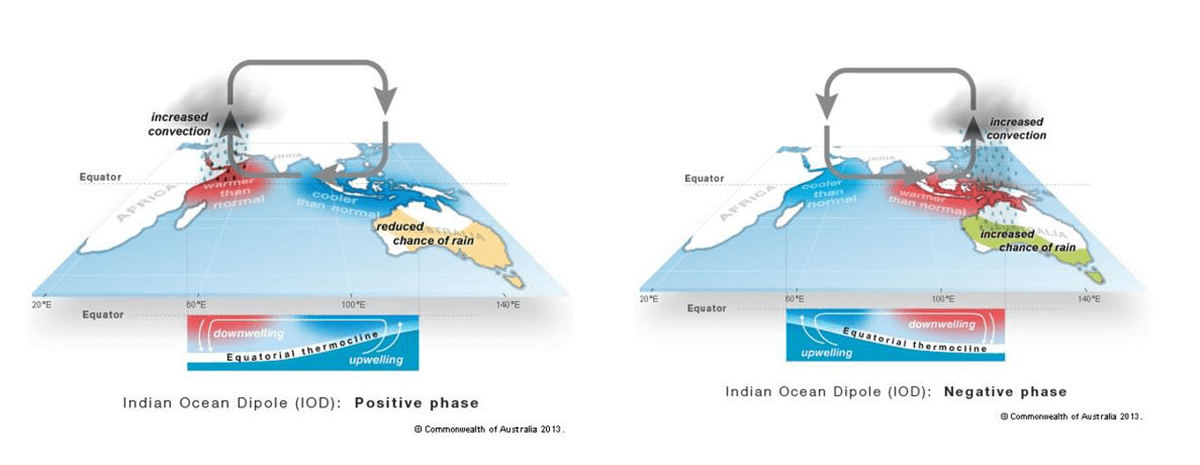

WHAT IS THE IOD?

Just like ENSO, an IOD event has three phases. A positive, negative and neutral phase. During a positive phase of the IOD, cooler-than-average waters reside off northwestern Australia. This results in less moisture with higher temperatures and below-average rainfall across central and southern Australia.

During a negative phase, westerly winds intensify across the equator, allowing warmer waters to push across northwestern Australia. These warmer waters increase moisture, resulting in large northwest cloud bands through the interior and southern parts of the continent. This, in turn, increases the threat of rain and flooding.

SOUTHERN ANNUAL MODE

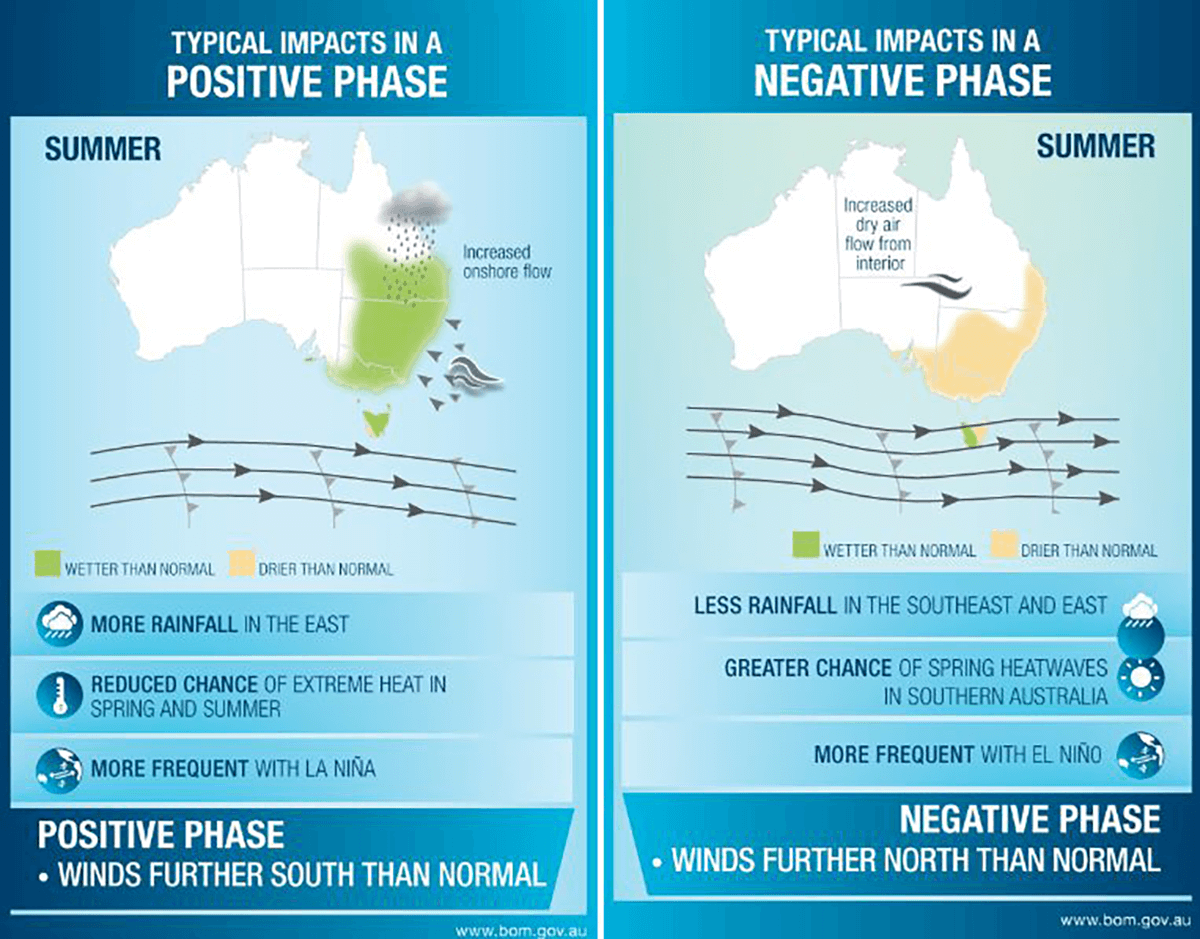

The Southern Annual Mode, or SAM as it’s otherwise known, is a climate driver that can influence the amount of rainfall and temperatures across southern Australia. The SAM has three phases, like ENSO and the IOD, with a negative, positive and neutral phase.

A positive phase of the SAM during the spring and summer contracts the belt of westerly winds towards Antarctica. This allows increasingly moisture-laden air from the Tasman and Coral Seas to be drawn inland, helping to increase rainfall. During a negative phase, this belt of westerly winds shifts further north towards the mainland. This decreases the threat of onshore easterly winds with decreasing rainfall for eastern Australia.

These three climate drives, in combination, contributed to Australia’s second-wettest Spring in history. Numerous locations across southern-inland NSW and northern Victoria recorded their highest rainfall on record.

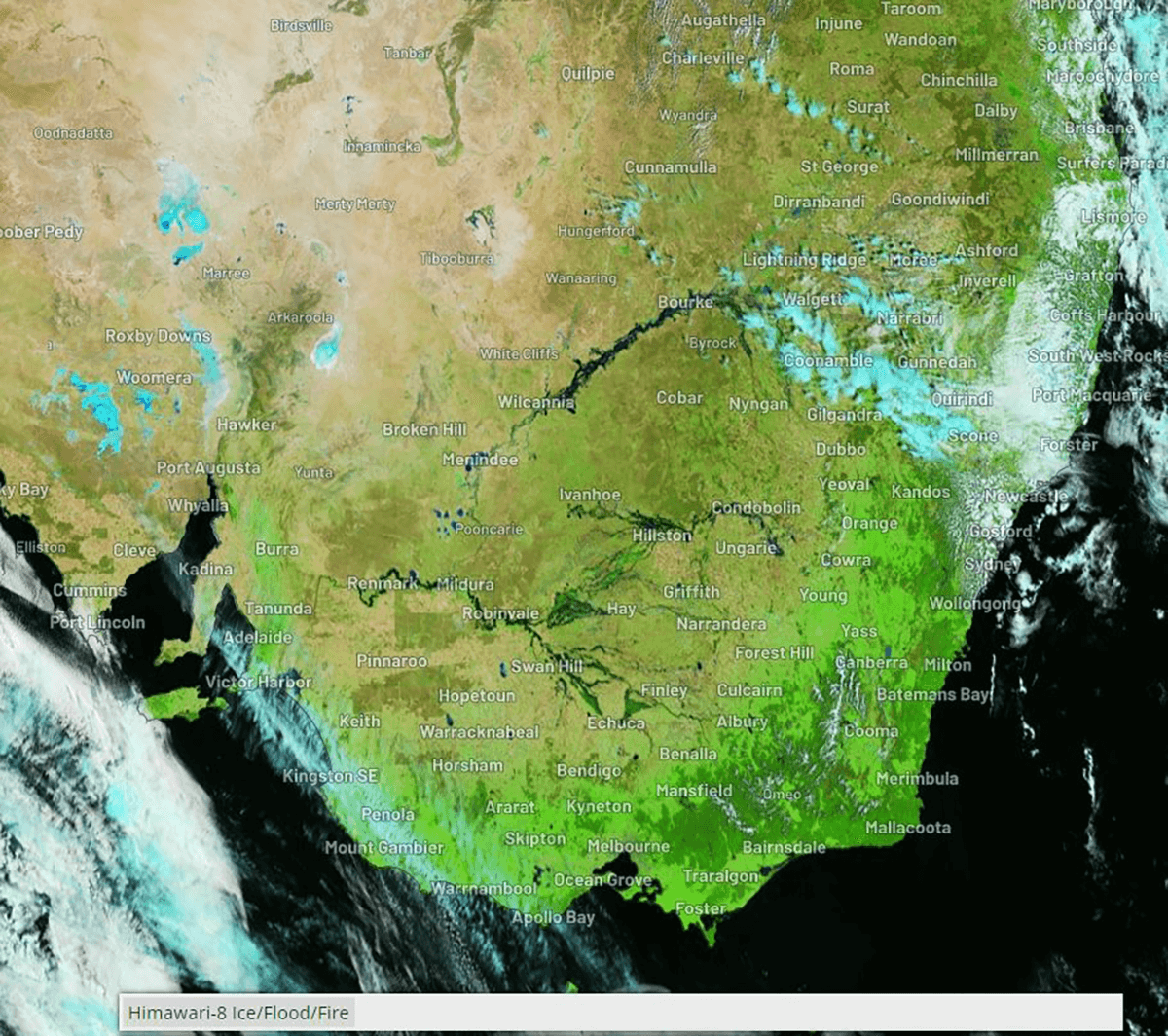

Prolonged major flooding has impacted many rivers and creeks across this region, with the Murray Darling basin (Australia’s largest river system) in full flood.

The Murray-Darling basin encompasses six of Australia’s seven longest rivers, stretching across five states and territories. It includes the Murray River, Australia’s longest river, which extends a staggering 2,508km from the border of eastern New South Wales and Victoria to South Australia.

The flooding across the basin has been so prolonged and extensive that these rarely-seen rivers are now visible on satellite imagery. The highest on-record spring rainfall also occurred across northern-inland parts of Western Australia. This was due to a strong negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole during the early Spring.

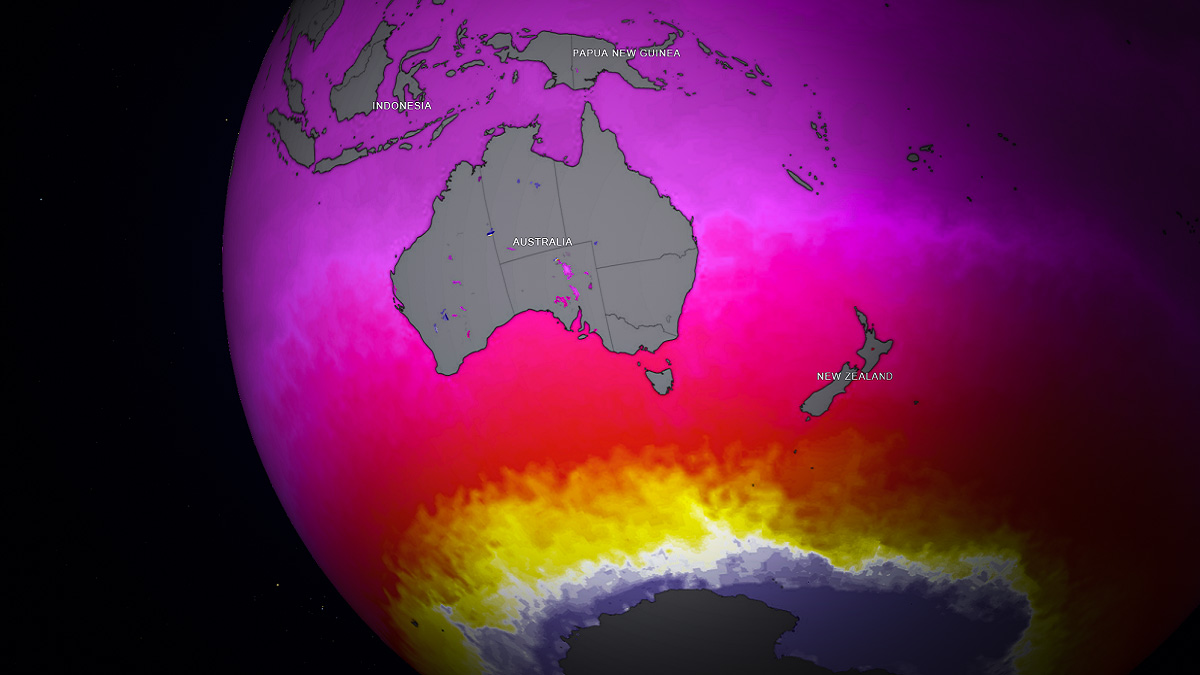

Satellite imagery from WeatherZone

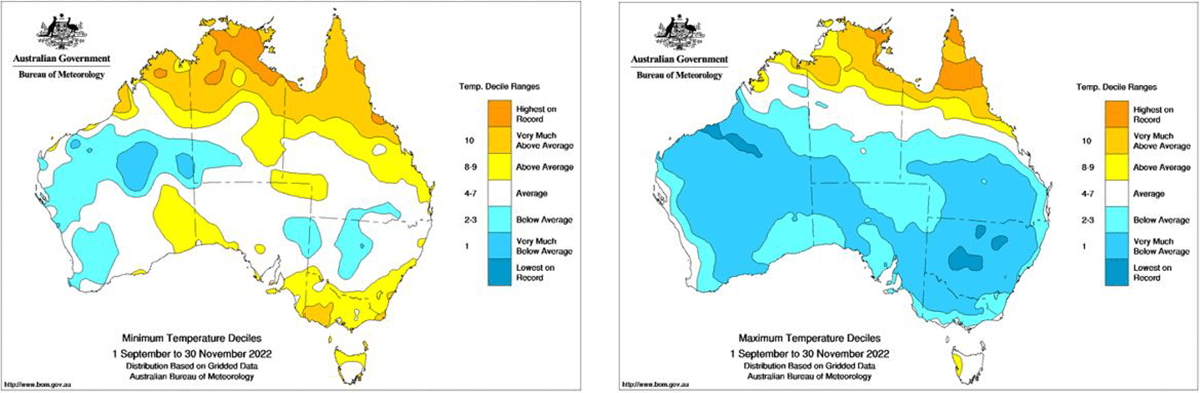

With an increase in cloudy conditions and above-average rainfall, below-average maximum temperatures occurred during the spring months for large portions of southern and eastern Australia. The exception was for the Top End in the Northern Territory and North Queensland, where some regions recorded their highest on record.

The area-averaged national mean temperatures were 0.75°C below average, while the national mean minimum temperature was 0.53°C above average. These temperature anomalies further showcase the influence of the three primary climate drives impacting Australia.

WITH A WEAK LA NIÑA EVENT – WHAT LIES AHEAD?

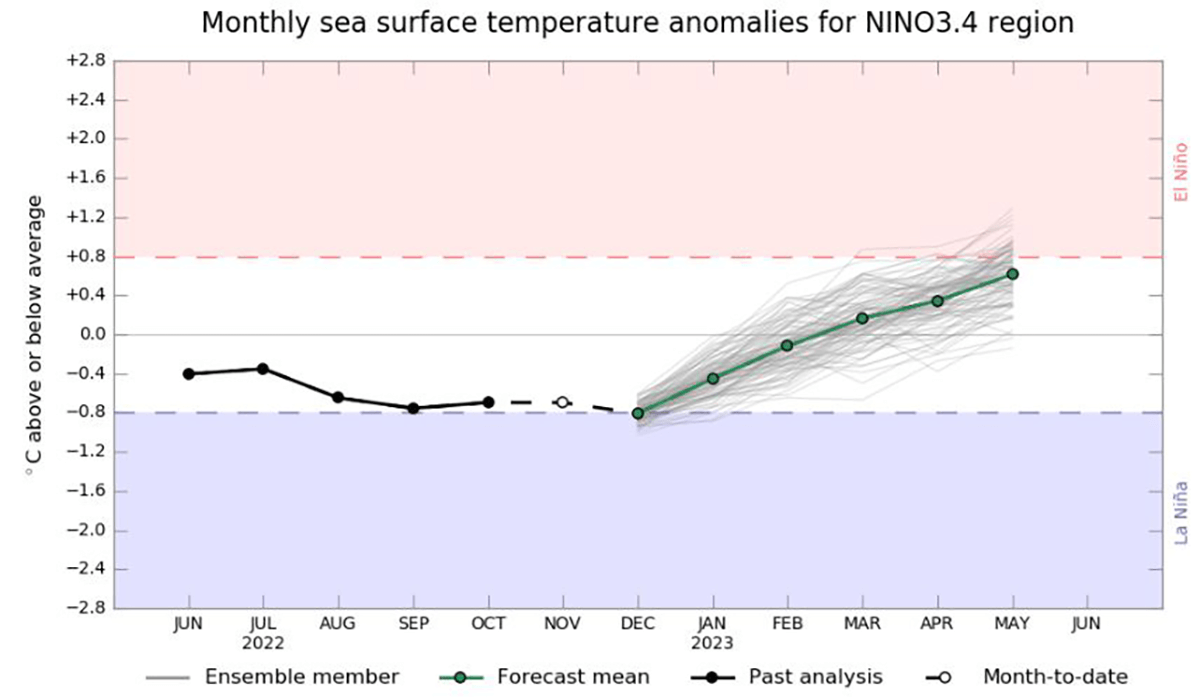

With such flooding prevalent across eastern and southern Australia, what lies ahead during the summer months with a continuing La Niña? The strong Indian Ocean Dipole event over the last several months is officially over, returning to a neutral phase.

Meanwhile, a weak La Niña event is ongoing; however, this, too, is expected to return to a neutral phase from January through April slowly. However, the effects of this La Niña will continue to linger during the summer, with the potential for El Niño to return in mid-to-late 2023.

Record-breaking rainfall from late winter through Spring has led to increased growth and potential fuel load across flood-affected areas of Queensland and NSW.

Despite below-average temperatures during Spring, warmer conditions will return over the summer as the current La Niña event continues to wane, with this increase in vegetation likely to dry out, increasing the threat of significant grass fires should any prolonged hot and windy conditions develop.

Here is also the video animation of the Australian rainfall deciles from 2019 to 2022. We can clearly see how anomalous the rainfall was this year.

WILL BUSHFIRES IN AUSTRALIA RETURN THIS SUMMER?

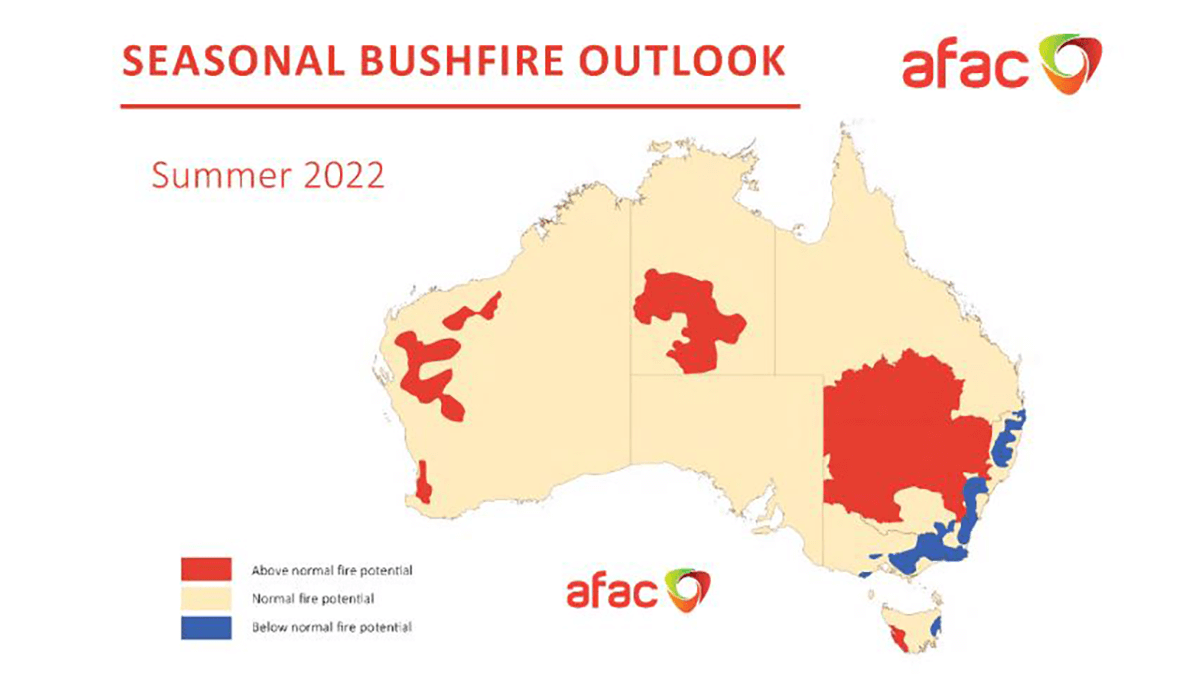

AFAC (The National Council for Fire and Emergency Services), in collaboration with the Bureau of Meteorology and fire agencies across Australia, released their seasonal bushfire outlook for summer 2022. This outlook showcases increased grass fire potential across southern-inland Queensland, New South Wales, parts of the Northern Territory, and inland Western Australia.

Fire-affected regions of eastern NSW and Victoria from the 2019/2020 season can expect below-normal fire potential due to a continued wet outlook across the summer months, despite an increase in fuel loads across this region which will remain damp.

Above the normal fire, the potential will also exist for western parts of Tasmania and the South West Land Division of Western Australia, which experienced drier than average rainfall conditions during Spring, mainly due to a continued positive phase of the Southern Annual Mode.

Image from AFAC

Bushfires are a natural part of Australia’s continued evolution. Despite wetter-than-average conditions for most of eastern Australia, fires still pose a significant threat to lives and properties. If you live within a fire-prone region or are surrounded by bushland, be fire-prepared! This can help mitigate the danger and may save your life. Firstly, have a plan; make an emergency and evacuation plan.

Cleaning out gutters and trimming overhead trees can help stop spot fires that may develop from embers being blown well downstream of the main bushfire. Remove any flammable items from around your house. Make sure you have quality access to water tanks, swimming pools, or town water, as well as quality access to fire emergency services.

Keep up to date with the current weather forecasts and prepare to leave early in a worst-case scenario.

Images used in this article provided by Windy, BoM, Weatherzone, AFAC