The cryosphere is a fundamental and integral part of the climate system, and it has important linkage and feedback with the major components of the Earth’s system. Here, we present the general concept.

DEFINITION AND GENERAL CONCEPTS

The term cryosphere derives from the Greek word kryo, i.e., cold, and collectively describes the portion of the Earth system at and below the land and ocean surface where water is frozen. The cryosphere includes snow cover, glaciers, ice sheets and shelves, freshwater ice (lakes and rivers), sea ice, icebergs, permafrost, and seasonally frozen ground.

On the broader definition, which is increasingly relevant today, the cryosphere includes planetary and other ice forms of the solar system and beyond.

The origin of the term cryosphere has been traced to the Polish scientist A.B. Dobrowolski, who used it in his 1923 book “The Natural History of Ice – Historia Naturalna Lodu,” written in Polish. After him, Shumskii in 1964 and Reinwarth and Stäblein in 1972 elaborated on the usage of this term.

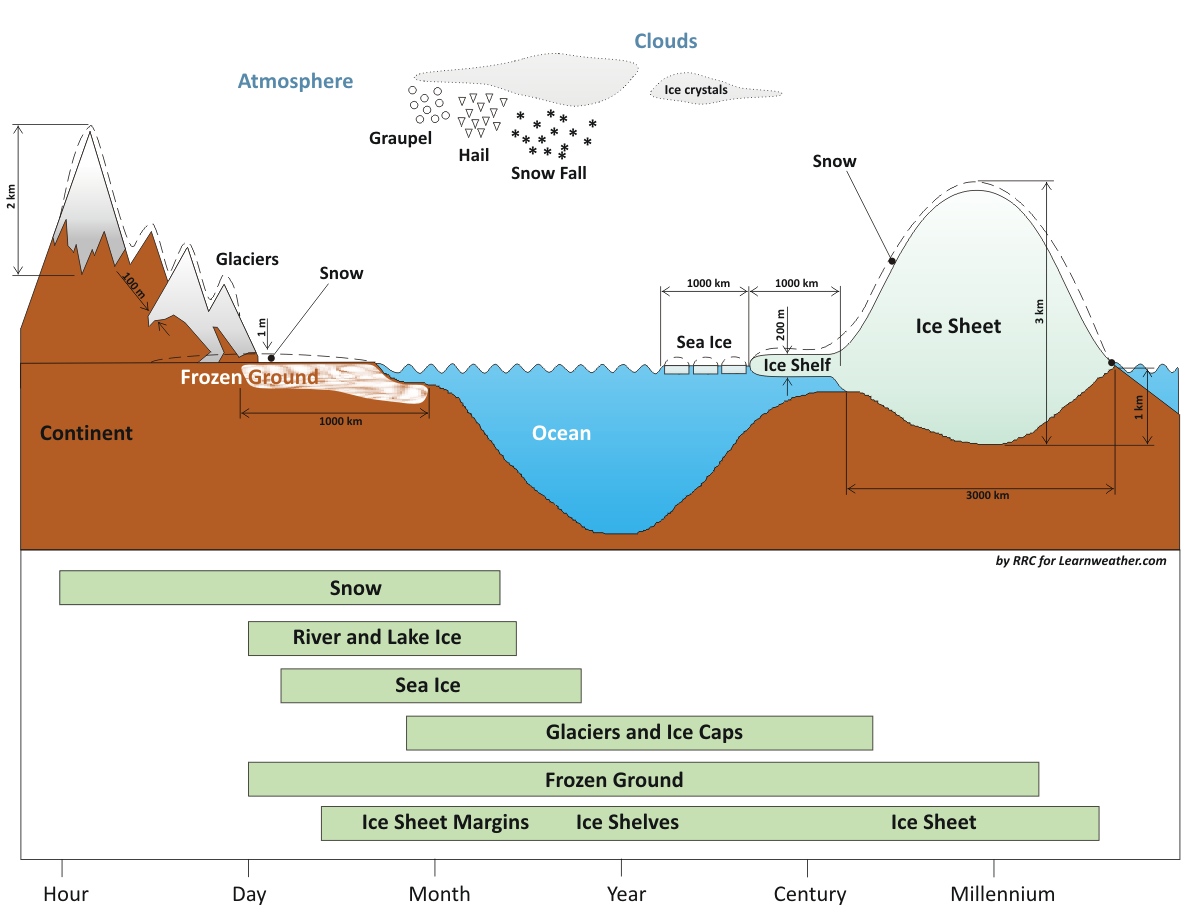

Components of the Cryosphere and their time scales. Redrawn after IPCC – AR4 WGI Chapter 4: Observations: Changes in Snow, Ice, and Frozen Ground

The cryosphere is a highly sensitive and integral component of the global climate system. It continuously expands and contracts, primarily in response to changes in summer temperature, snowfall, and the snow-ice albedo. Furthermore, it has crucial linkages and feedback mechanisms with the atmosphere and hydrosphere through its influence on surface energy and moisture fluxes. Mass and energy are constantly exchanged with other major Earth system components, such as the biosphere and lithosphere.

As such, the cryosphere affects atmospheric processes such as clouds, precipitation, and surface hydrology through changes in the amount of fresh water on lands and oceans. It locks up freshwater on continental ice masses when it freezes and releases much of it when snow or ice melts.

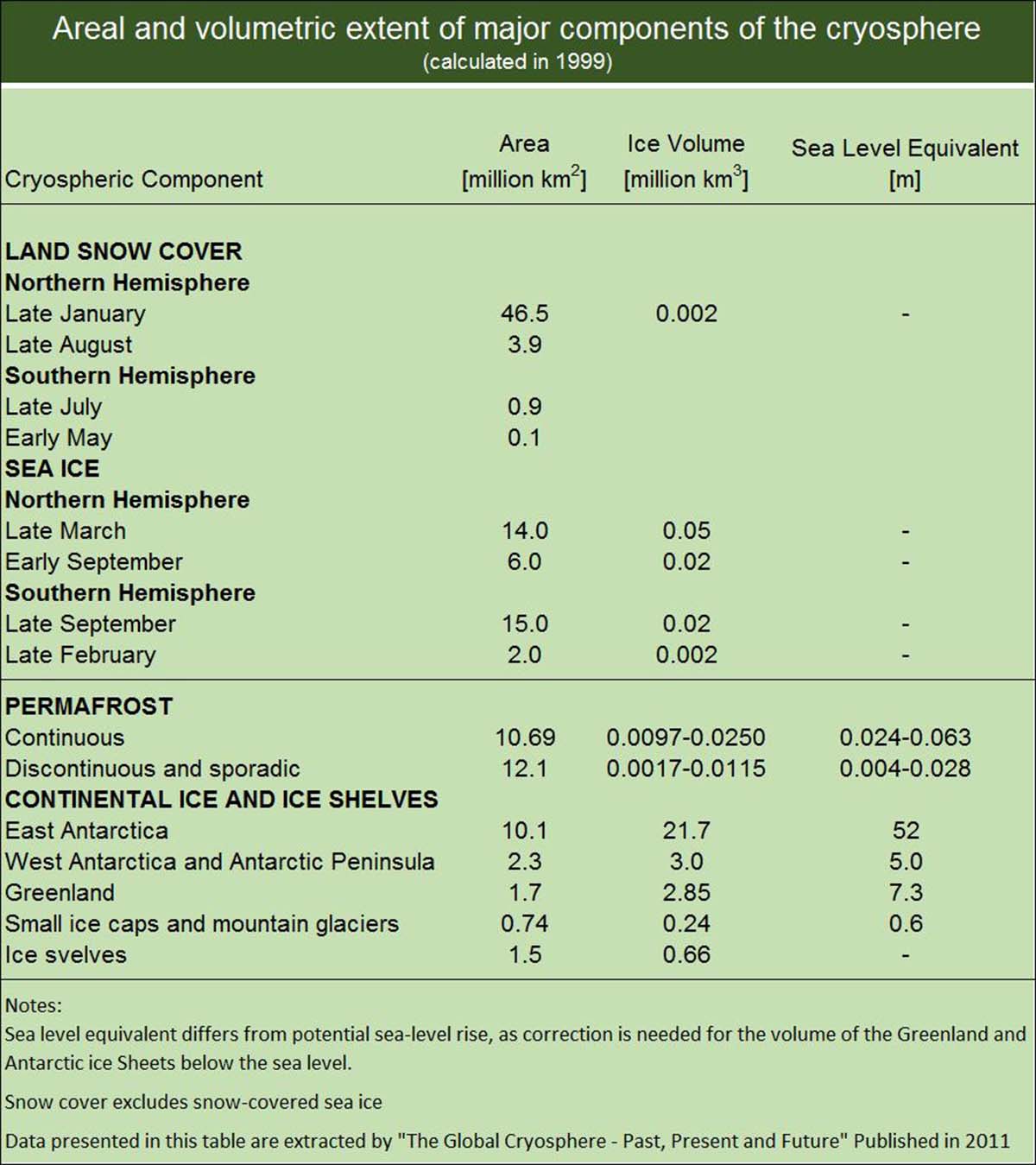

The latter affects thermohaline oceanic circulation. In the table below, we reported all the cryospheric components and sea-level equivalents from different sources from the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere (2019).

Table of cryospheric components and sea level equivalent from different sources (The Global Cryosphere 2011; IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, 2019)

Glaciers or ice sheets cover around 10% of Earth’s land area. Ice sheets are the greatest potential source of fresh water, holding approximately 77% of the global total. Only a tiny fraction (0.5%) lies in ice caps and glaciers outside Antarctica and Greenland, accounting for about 64 m of sea-level equivalent. Antarctica accounts for 90% of this (57 m), and Greenland accounts for almost 10% (7.3 m).

The cryosphere has both seasonally varying features and more permanent components. The mean snow cover extent in the Northern Hemisphere ranges from ~ 46 million km² in January to 3.8 million km² in September, with the second largest extent of any cryosphere component with a mean annual of approximately 26 million km².

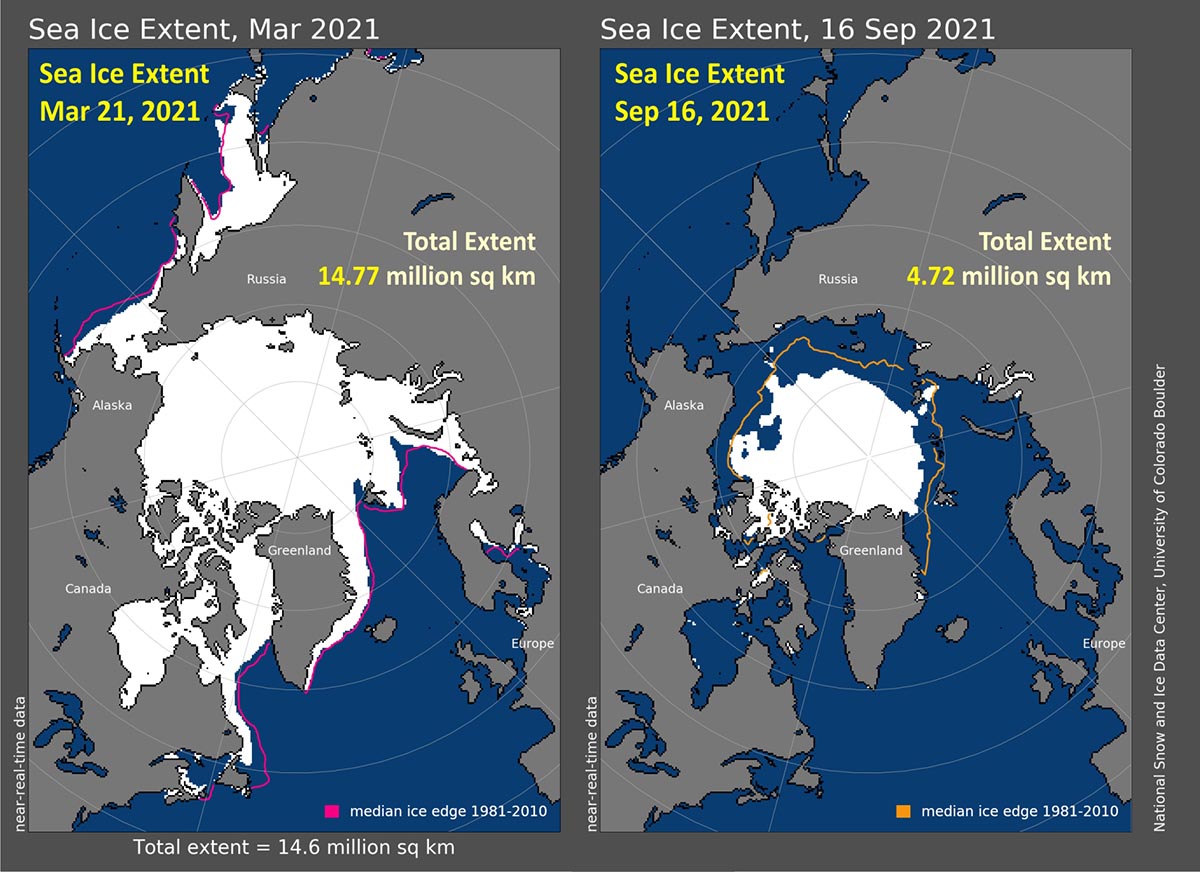

The Northern Hemisphere sea ice extent varies by a factor of two (from 7-9 million km² in September to a maximum of 14-16 km² in March during 1979-2004; lately, late summer ice extent has been much smaller). On the other hand, sea ice extent in the Southern Hemisphere changes seasonally by a factor of five, from 3-4 million km² in February to 17-20 million km² in September.

Arctic Sea Ice extent in March and September 2021, when the minimum and maximum sea-ice extent are respectively reached

ICE UNDER THE LENS

We have so far discussed some general aspects of the global cryosphere, but we have not explicitly addressed its primary element: ice.

Ice plays a vital role in our planet’s energy system. The reason lies in the unique properties of ice crystals, which derive from the specific properties of water molecules, making them the key to life.

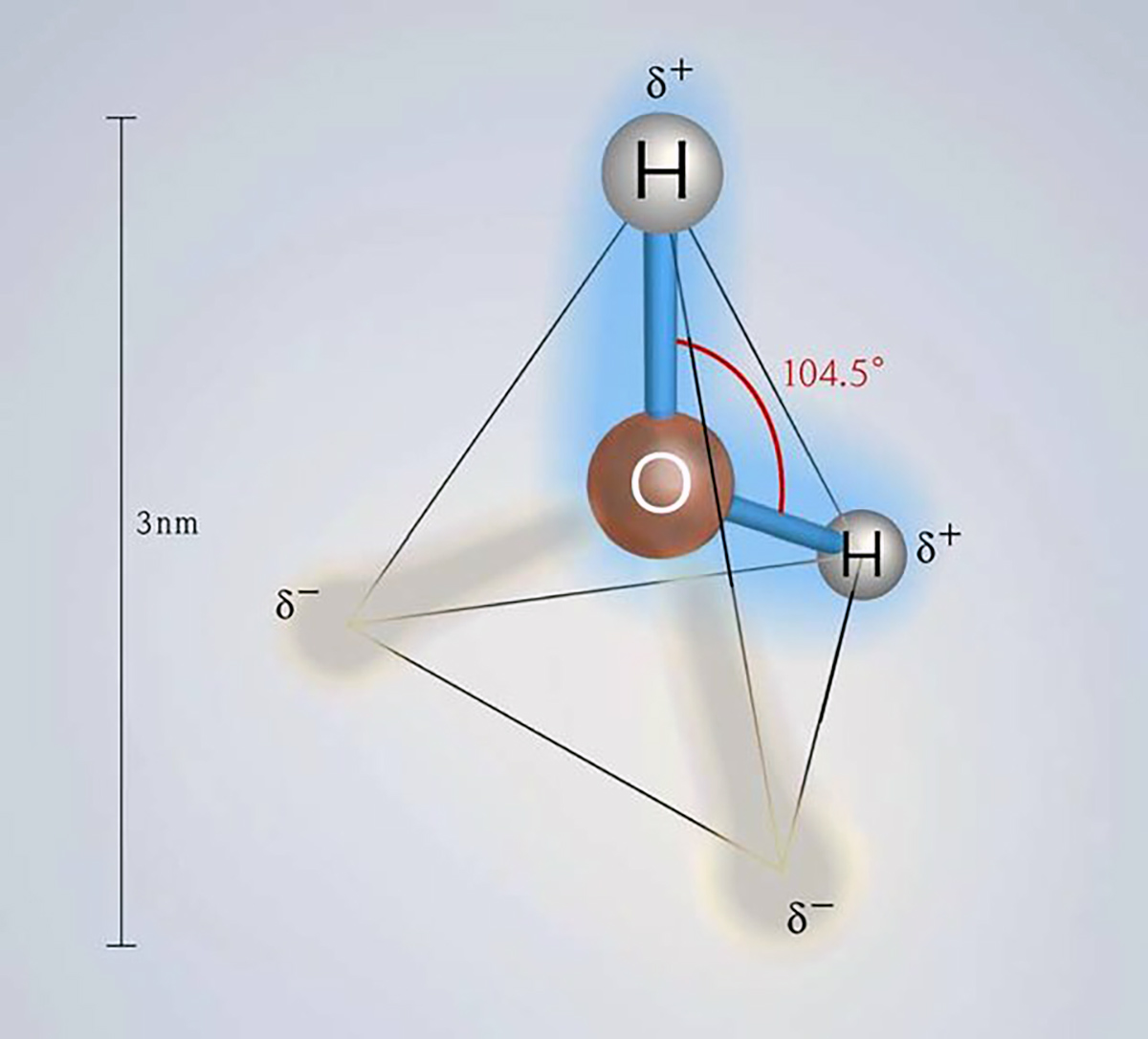

The fundamental structure of ice is tetrahedral, and ice crystals preferentially grow along the axes of the basal plane rather than vertically. To understand the characteristics and behavior of sea ice, it is crucial to highlight that crystal growth predominantly occurs in the horizontal planar direction as the ice surface thickens through freezing.

Water is an unusual molecule because, unlike most substances, its solid form is less dense than its liquid form. The density of water is 1000 kilograms per cubic meter (historically defined as the kilogram). In contrast, the density of ice is 917.4 kilograms per cubic meter.

Seawater has a higher density than pure water and usually equals 1025 kilograms per cubic meter. The density difference between water and ice is about 10%. This is why 10% of the mass of an ice sheet or iceberg emerges above the sea surface while the rest remains underwater.

Now, let’s consider what would happen if the density difference of water were reversed, as it is for most substances. In this case, ice would sink in water, causing lakes, rivers, and even the ocean to freeze almost entirely. When ice forms on the surface of a body of water—such as the sea surface due to low temperatures—it would sink to the bottom, creating a frozen layer there.

All benthic life forms would be eliminated. In the case of a lake, the ice layer at the bottom would continue to grow, leaving only a thin layer of unfrozen water on the surface by the end of winter—if even that. The entire lake ecosystem would be wiped out.

In the real world, sea ice forms a thin layer on the surface that protects the ocean from further freezing. Thus, ice acts as an insulating layer between the atmosphere and the sea. In the hypothetical scenario where ice is denser than water, the ocean surface would constantly be exposed to the atmosphere. It could cool freely during winter, continuously absorbing the cold.

Ice skating would also be impossible if ice were denser than water. In reality, the intense pressure of the skate blade on the ice surface lowers the melting point, and the ice just below it melts, lubricating it. If water were less dense, the pressure on the ice would raise the melting point, making ice skating impossible.

Image from travelalberta.com

Image from travelalberta.com

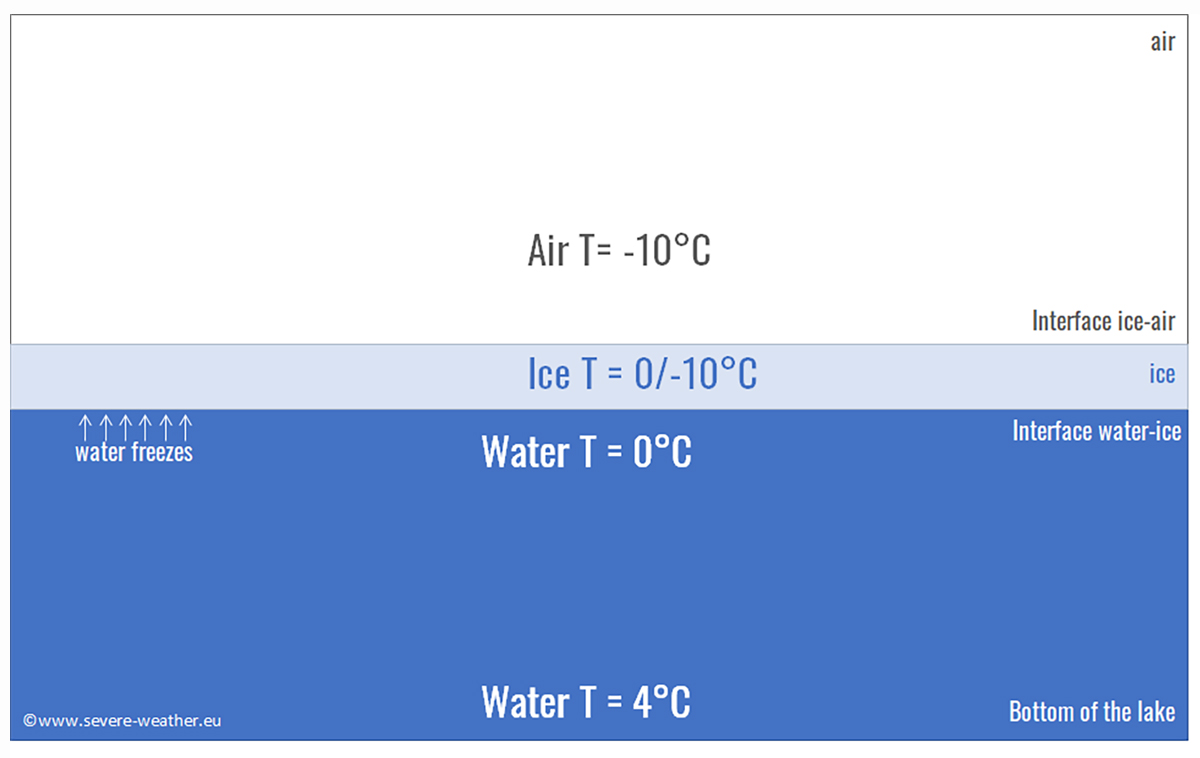

But let’s go back to the real world. The maximum density of water is reached at around 4 degrees Celsius. This means that in autumn, a river or a lake located at high latitudes in contact with cold air temperatures will cool the surface water, causing it to sink initially and be replaced by warmer water from below. This happens because warm water is usually less dense than cold water, and this process is called convective overturning.

The phenomenon we just described continues until all the lake water has cooled to 4 degrees Celsius. At this point, the surface water can cool rapidly and reach 0 degrees Celsius, the freezing point of fresh water. However, the deeper parts of the lake remain at 4 degrees Celsius. This is why the surface of a lake freezes quickly in autumn, while it takes much longer for the entire lake to freeze down to the bottom. In most cases, winter ends before this happens. However, seawater does not have this maximum density temperature. So, what happens in the sea?

SEA ICE

Seawater becomes denser as it cools until it reaches the freezing point. This transition in behavior from freshwater to saltwater occurs when the salinity exceeds 24.7 parts per thousand (ppt) of dissolved salt in water. Most seawater has a 32-35 ppt salinity, while only a few isolated seas have a salinity lower than 24.7 ppt. This occurs, for example, near the mouths of large Arctic rivers or the Baltic Sea. The generic term brackish defines this transition at 24.7 ppt.

sea ice forming around Svalbard

When seawater is cooled in autumn, convective overturning continues until all the water reaches freezing. The significant difference is that this freezing point is below 0 degrees Celsius because the presence of salt lowers it to -1.8 degrees Celsius for seawater. This effect is called cryoscopic lowering and is why salt is used on icy roads in temperate regions.

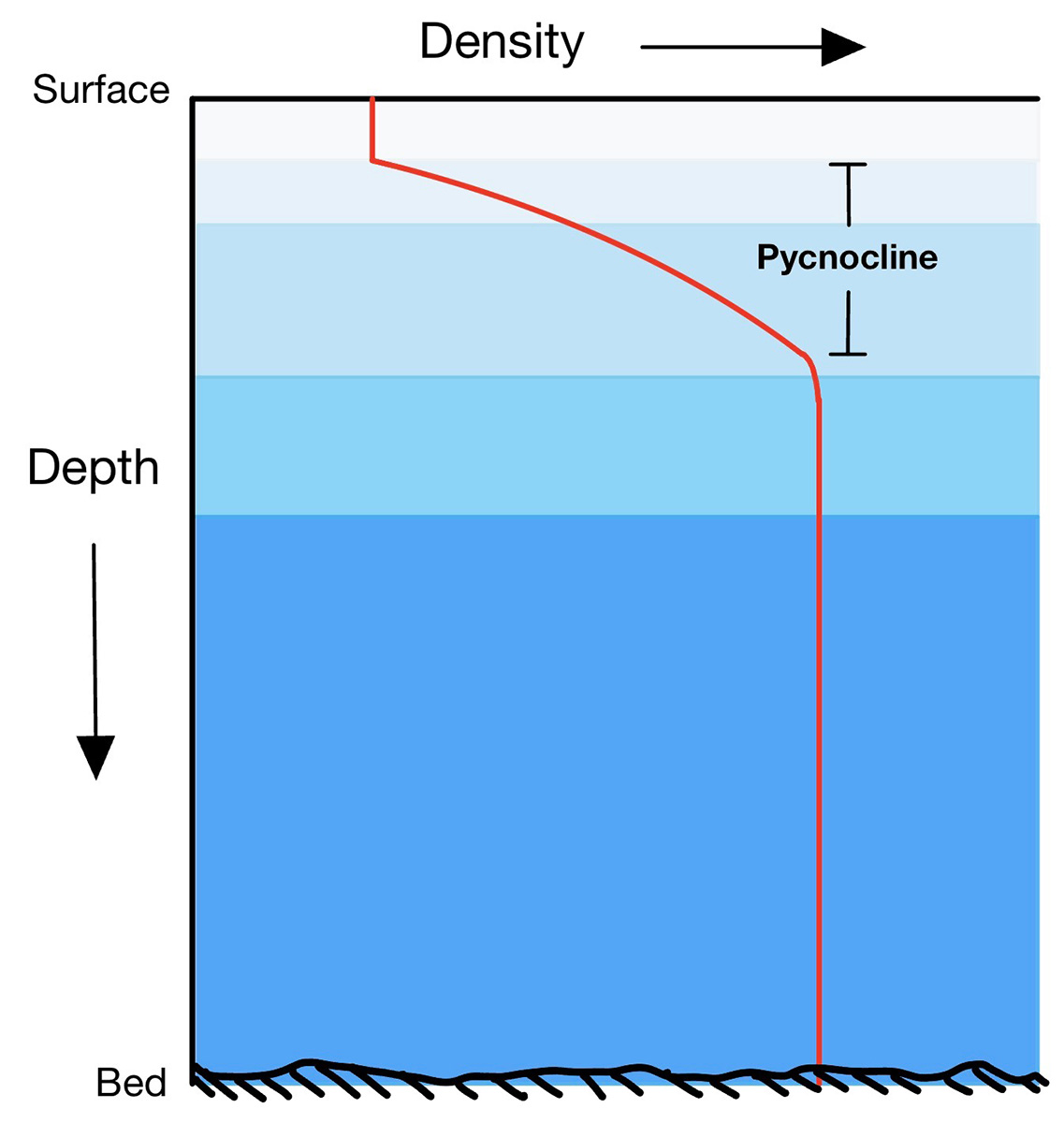

What prevents the entire depth of the ocean from cooling before freezing can occur on the surface is that the sea consists of layers characterized by different types of water with different origins, moving in different directions and speeds. There is a rapid change in density between one layer and another, called the pycnocline. For this reason, convection must extend only to the bottom of the surface layer.

Image from wikipedia.com

In the Arctic, this layer is called Polar Surface Water, while the underlying layer is called Atlantic Water, as it reaches the Arctic from the Atlantic Ocean. The fact that ice floats on the water means that sea ice forms a thin cover on the sea surface, allowing ocean circulation to continue below and life to exist both in the depths of the ocean and, especially, near sea ice.

Another fundamental property of ice is its extraordinarily high latent heat of fusion. Latent heat is the heat required to melt ice when it is already at the melting point. This value is 80 kilocalories per kilogram.

Phase change transition diagram. States matter schema. Evaporation, condensation, sublimation, deposition, freezing, melting, vaporization. Water, ice. Image from stock.adobe.com

Latent heat should not be confused with specific heat, defined as the heat required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by 1 degree Celsius. The specific heat of water is only 1 kilocalorie per kilogram, equal to 4186 joules.

This means that while only 1 kilocalorie of heat is needed to raise the temperature of 1 kilogram of ice by 1 degree Celsius, it is necessary to provide 80 kilocalories to melt it. In practice, the same amount needed to melt it could heat the same cold water mass to +80 degrees Celsius. The image below comes from Zachary Labe.

This aspect is of vital importance to Earth. On a planetary scale, the latent heat of fusion of water acts as a huge heat reservoir, a buffer for climate change. A fundamental example is the behavior of sea ice during the summer.

The ice melts, but as long as it does not melt completely, it maintains the air temperature near the surface and the temperature of the water under the ice at around 0 degrees Celsius. This happens because warmer air would be used to melt more ice, and it would cool itself during this process. As long as it is present in summer, sea ice provides a natural air and water conditioning system for the ocean.

Grease ice or frazil forming over the sea surface. Details in the following paragraph

Grease ice or frazil forming over the sea surface. Details in the following paragraph

HOW DOES SEAWATER FREEZES?

But how does seawater freeze? Let’s begin by considering calm water freezing under quiet conditions, without waves. As the cold atmosphere draws heat from the water’s surface, the surface molecules start to freeze. This process forms a thin layer of independent ice crystals, initially small disks and stars floating horizontally on the sea surface, with diameters of 2-3 millimeters.

Each disk or star grows dendritically, branching out in 6 directions outward along the surface like a snowflake. These randomly shaped crystal pieces form a suspension that increases the surface density of the water. A kind of semi-liquid mixture is formed called frazil or grease ice, literally oily ice.

Nilas (young ice) are in their initial phase when it is almost transparent and dark. Svalbard, Norway

Nilas (young ice) are in their initial phase when it is almost transparent and dark. Svalbard, Norway

Under calm sea conditions, frazil crystals freeze by aggregating to form a layer of young ice called nilas in its initial phases. When this nilas layer is only a few centimeters thick, it is transparent and is referred to as dark nilas. As it thickens, it first takes on a gray color and then becomes whitish, eventually turning opaque.

Once the nilas have formed, the sea can be considered physically separated from the atmosphere. At this point, a different type of growth begins. Water molecules start freezing by adhering to the bottom of the existing ice layer. This process is called freezing growth.

Both dark and opaque nilas coexist in the freezing process. Svalbard, Norway

Both dark and opaque nilas coexist in the freezing process. Svalbard, Norway

With further growth, this process leads to the formation of ‘first-year ice,’ which reaches a thickness of about 1.5 meters in the Arctic in a single season and approximately 0.5-1 meter in Antarctica. What happens to the dissolved salt in seawater? Salt molecules cannot enter the crystalline structure, although some salt remains trapped in liquid pockets known as brine cells.

For this reason, first-year ice is still slightly salty, with a salt concentration of about 10 ppm. The expulsion of brine from these cells occurs as the entire cell attempts to freeze when the temperature drops. In the Arctic, only about half of the ice volume forms this way.

The map shows sea ice thickness in the Northern Hemisphere, excluding the Baltic Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The data is based on model calculations from the Denmark Meteorological Institute. The rest consists of deformations of pre-existing ice piled up into linear pressure ridges and openings created by this process, known as leads.

The ice layers formed through the processes described earlier are constantly in motion, guided by the frictional force of the wind on their surface and by marine currents on their underside. Compressive, divergent, and shear stresses continuously modify the Arctic sea ice.

The sea ice that forms in shallower waters or near the shore, where the atmosphere only needs to cool a thin layer of water to allow the surface to freeze, is called landfast or fast ice because it freezes the ocean to the seafloor. A bit farther out, the ice floats but remains stationary because it is attached to formations anchored on the seafloor.

Sea ice that is not fast refers to drift ice, and if the concentration exceeds 70%, it is called pack ice. When sea ice concentration is lower than 15%, this is considered open water, and the boundary between open water and ice is called the ice edge. Zachary Labe provides a tremendous graphical example below illustrating the differences between the terms sea ice extent, concentration, and thickness.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN CRYOSPHERE AND THE CLIMATE SYSTEM

Interactions between the cryosphere and the climate system operate mainly through five mechanisms:

- ice albedo feedbacks

- insulation of land surface and ocean, respectively, by snow cover and floating ice

- hydrological cycle due to the storage of water in snow, glaciers, ice caps, and ice sheets

- latent heat involved in phase changes of ice/water

- modulation of water and energy fluxes between the land and atmosphere by seasonally frozen ground and permafrost

The main issues linked to the shrinking cryosphere due to Global Warming are sea-level rise, mountain hazards, and permafrost thawing, particularly in polar regions. Moreover, on a regional scale, many glaciers and ice caps play a crucial role in freshwater availability.

Changes in the ice mass on land have already contributed to recent changes in sea level of approximately 20 cm in the last century. During the last glacial maximum, about 21,000 years ago, the sea level was about 125 meters (about 410 feet) lower than it is today. This happened because of colder conditions globally, 5-7 °C lower than present days, stored snow and ice on land, and the oceans were deprived of it.

Changes in ice-albedo due to dust, fine debris, and black carbon strongly affect alpine glaciers, varying the ratio between reflected and absorbed solar radiation. Glacier of Vedretta Piana – Eberferner. Photo by Renato R. Colucci

The projected responses of the cryosphere to current and past human-induced greenhouse gas emissions and ongoing global warming include climate feedback, changes over decades to millennia that cannot be avoided, thresholds of abrupt change, and irreversibility. Moreover, human communities close to coastal environments, small islands, polar areas, and high mountains are particularly exposed to cryosphere change.

Below are three examples of the Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine cryosphere. We will explore these aspects separately and in greater detail in future discussions on glaciers, ice sheets, and ice shelves.

Moreover, all the aspects of water in its frozen state will be discussed, starting from ice crystals in the highest tropospheric clouds to the ‘hidden’ ice in the ground in permafrost terrains. We have extensively discussed permafrost and some of its characteristics in this dedicated section. Last, we’ll discuss also the solar system’s different forms of the cryosphere.

The Esmarkbreen glacier terminus in the Oscar II Land is seen over the disintegrating sea ice surface of Isfjorden: April 2011, Svalbard (northern Norway). Photo by Renato R. Colucci

A small Antarctic ice shelf around Coronation Island. Photo by Renato R. Colucci ©PNRA-ENEA

The terminus of the Marmolada glacier (western tongue) in the Italian Dolomites was at the end of Summer 2018. Photo by Renato R. Colucci

A permanent Ice deposit in a cave of the South East Alps in Italy. Photo by Renato R. Colucci

In false colors, the polar cap of Sputnik Planum (planet Pluto) is surrounded by mountains that have been eroded and shaped by old glacial activity. Image credit: © NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

See also:

Methane explosions strike the frozen ground in Siberia, sparking wild theories about their origins