Permafrost is an important aspect of the cryosphere, a fundamental and integral part of the climate system in periglacial landscapes. Here, we present the general concept, especially the climatic conditions leading to the formation and preservation of permafrost in different environments on Earth.

DEFINITION

Permafrost, by definition, refers to the ground that remains below 0°C for at least two consecutive years. More briefly, we can define it as perennially cryotic ground. The term cryotic, better than frozen, which implies the presence of ice, suggests a ground temperature below 0°C.

Water in its solid phase is not necessary to characterize the Permafrost, which is exclusively defined by the thermal state of the ground. For this reason alone, it is essential to remember that permafrost thaws while ice melts.

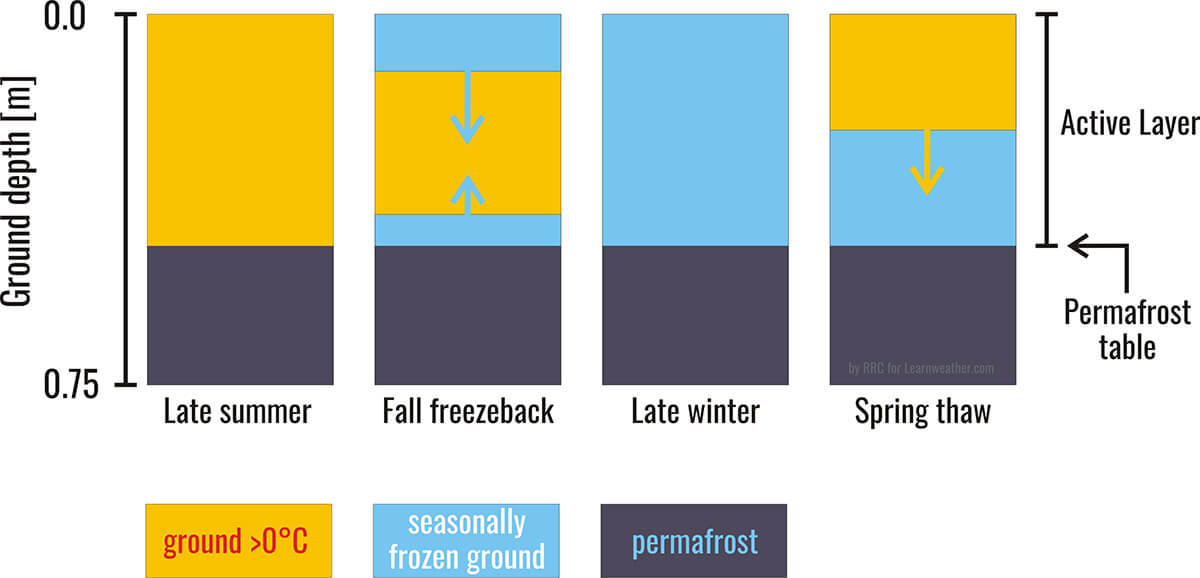

Except under very special circumstances, permafrost does not extend to the ground surface due to solar radiation, and above-freezing temperatures thaw the uppermost layer of ground during summer. Exceptions exist under perennial snow beds or cold-based glaciers. The uppermost layer, which freezes and thaws on a seasonal basis, is called the Active Layer.

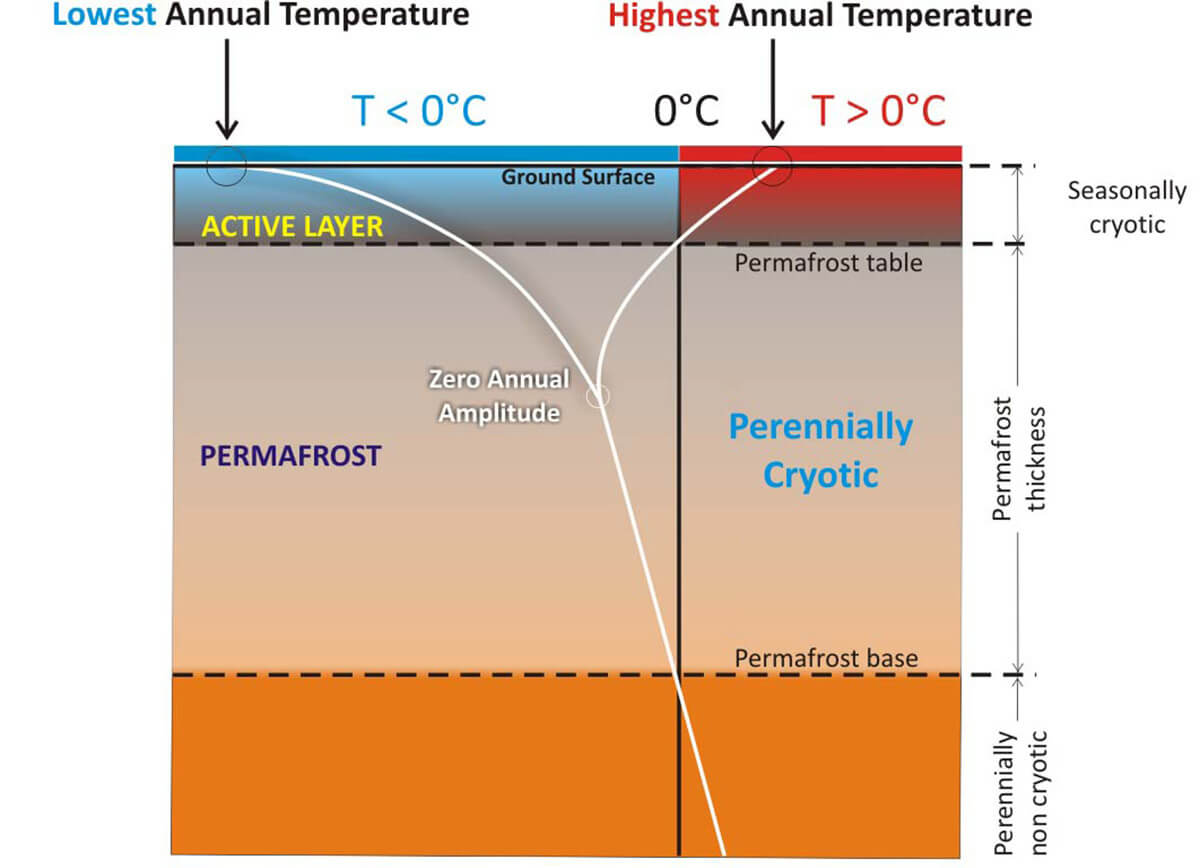

To understand how the temperature in the ground behaves in areas interested in permafrost, we drew the sketch above. The “Y” diagram explains how the ground temperature behaves from the surface to depth. Annual extremes are the most significant close to the surface, becoming gradually smaller and moving down.

At a certain depth, the temperature is constant all year round, and this is the ‘Zero Annual Temperature’ depth. From this depth, the temperature constantly rises following the geothermal gradient at 25-30°C per kilometer (72-87 °F per mile).

When the ‘Y’ intersects the 0°C isotherms in the ground, the Permafrost table is located just below the Active Layer. Below this depth, we find the Perennially Cryotic layer or the Permafrost layer. When the ‘Y’ intersects the 0°C isotherms in the ground for the second time, we reach the Permafrost base. From this depth, the ground is perennially NON-cryotic and always thawed.

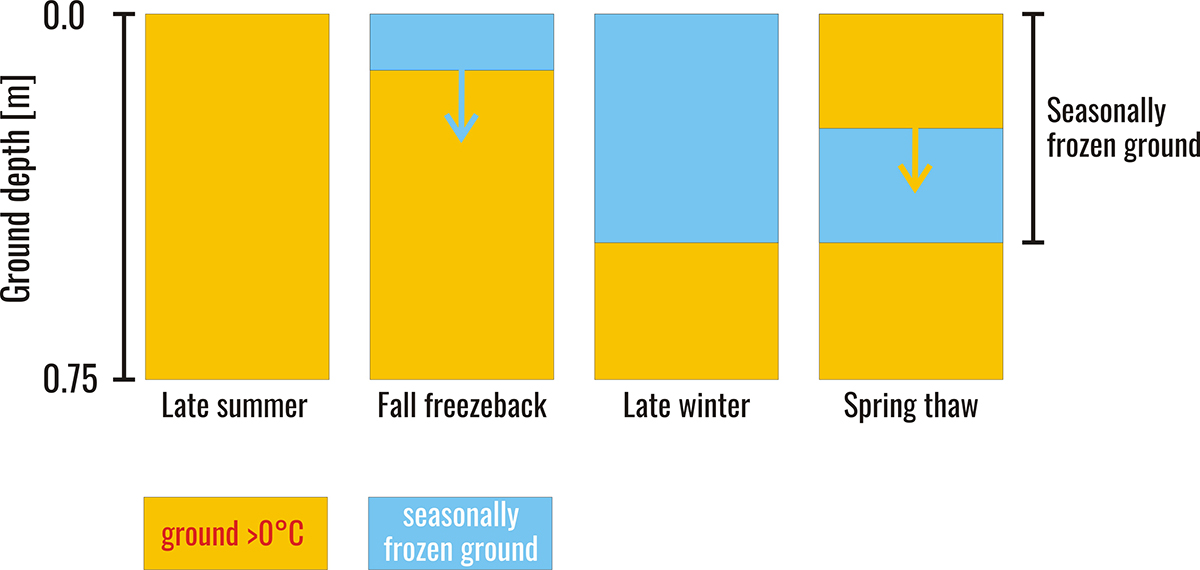

There is a well-defined difference in the behavior of the ground in permafrost or non-permafrost terrains. Seasonally frozen ground, or more strictly seasonally cryotic ground, describes ground undergoing a seasonal cycle of freezing and thawing.

Usually, it refers to the uppermost layer of the ground in cold environments where permafrost is not present. The images above (seasonally frozen ground in a permafrost-free environment) and below (above the permafrost) are oversimplified but highlight what happens in the ground during the seasonal cycles.

HOW PERMAFROST IS REACTING TO GLOBAL WARMING

Permafrost is a key component of the cryosphere and occupies around a quarter of the Earth’s land in the Northern Hemisphere. The change in surface energy balance triggering permafrost degradation may be caused by regional changes in climate, such as longer or warmer summers or increased winter snowfalls, which insulate the ground from the atmosphere. Another cause could be human-induced or natural deforestation, like a forest fire.

How does the permafrost react if the ground warms for one of these reasons? We created the GIF animation below to understand what happens when such a circumstance occurs. If the ground warms up, the surface temperature extremes will rise. The same will happen when proceeding in depth. Consequently, the ‘Y’- diagram will move to the right while the permafrost is warming.

As you can easily see in the animated GIF, the Active layer will deepen, and the permafrost will become thinner.

PERMAFROST AND PERIGLACIAL ENVIRONMENTS

The term periglacial was initially used to describe the climatic and geomorphic conditions of areas peripheral to Pleistocene ice sheets and glaciers. Modern usage refers, however, to a broader range of cold climatic conditions regardless of their proximity to a glacier, either in space or time. In addition, many, but not all, periglacial environments possess permafrost, but they appear all to be dominated by frost action processes.

In line with this view, the English version of the Multi-Language Glossary of Permafrost and Related Ground-Ice Terms compiled by the International Permafrost Association Terminology Working Group defines the term periglacial as the conditions, processes, and landforms associated with cold, nonglacial environments.

A typical Arctic periglacial landscape with patterned ground in the Spitzbergen-Svalbard credits Dreamstime

The geographical extent of present-day periglacial activity is not easily distinguished. Still, the general view is that the actual periglacial zones include all non-glaciated regions where frozen ground and/or thawing and freezing of the ground considerably affect landform development. Starting from this assumption, we understand how this model strongly relates to the geomorphological concept.

In other words, the distribution of resultant landforms derived from frost-action processes defines the extent of the periglacial domain. Depth and frequency of seasonal ground freezing and thawing, the depth of winter snow cover, the seasonal availability of liquid water in the upper level of the ground, erosion, and deposition processes are some of the main parameters in a periglacial environment, all driven by the climate.

Periglacial landscape in Iceland with patterned ground and polygons credits Dreamstime

PERIGLACIAL CLIMATES

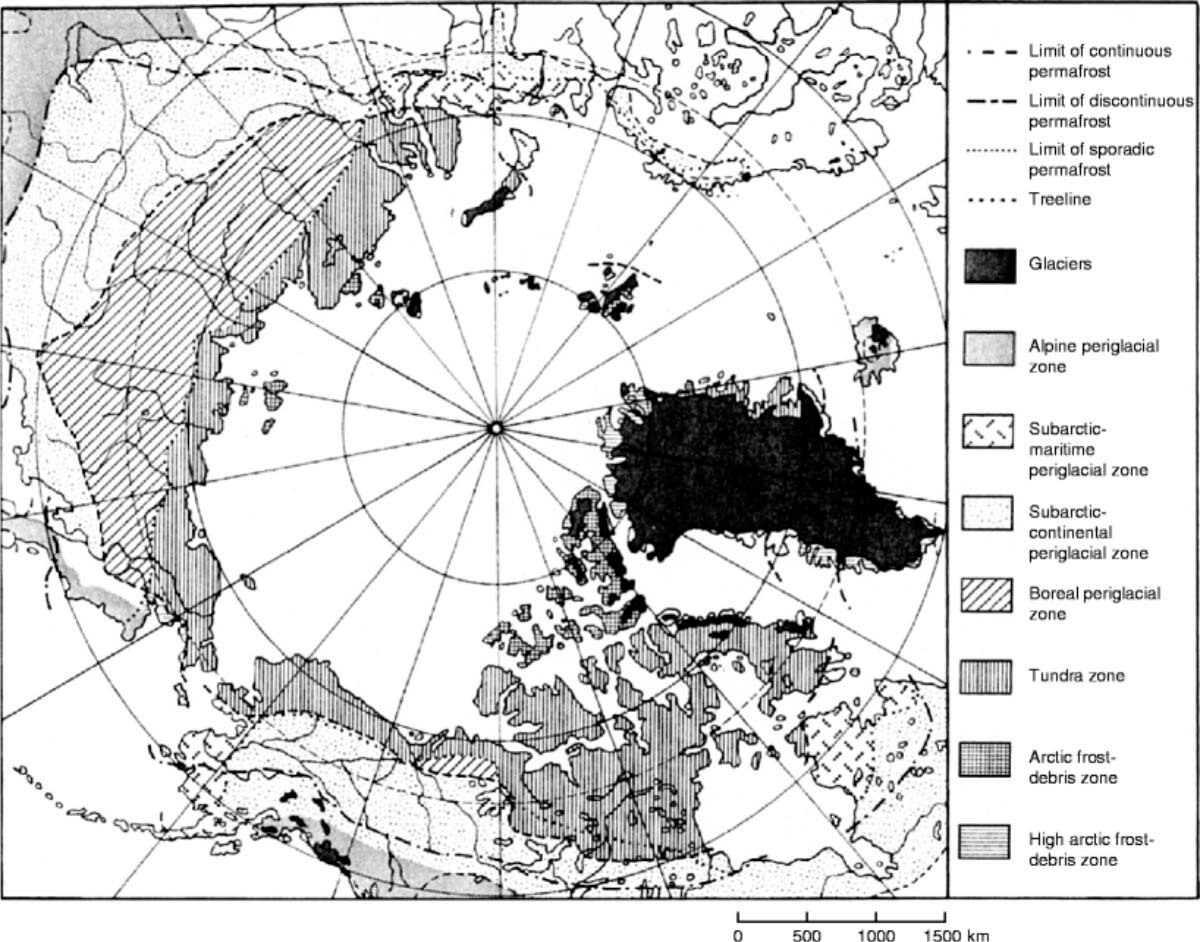

The periglacial domain refers, by definition, to the global extent of the so-called periglacial zone. Several different periglacial zones can be recognized based on the spatial association of certain microforms and their climate threshold values. They occur as tundra zones in the high latitudes as forested zones south of the treeline, and in high-altitude alpine regions of temperature latitudes.

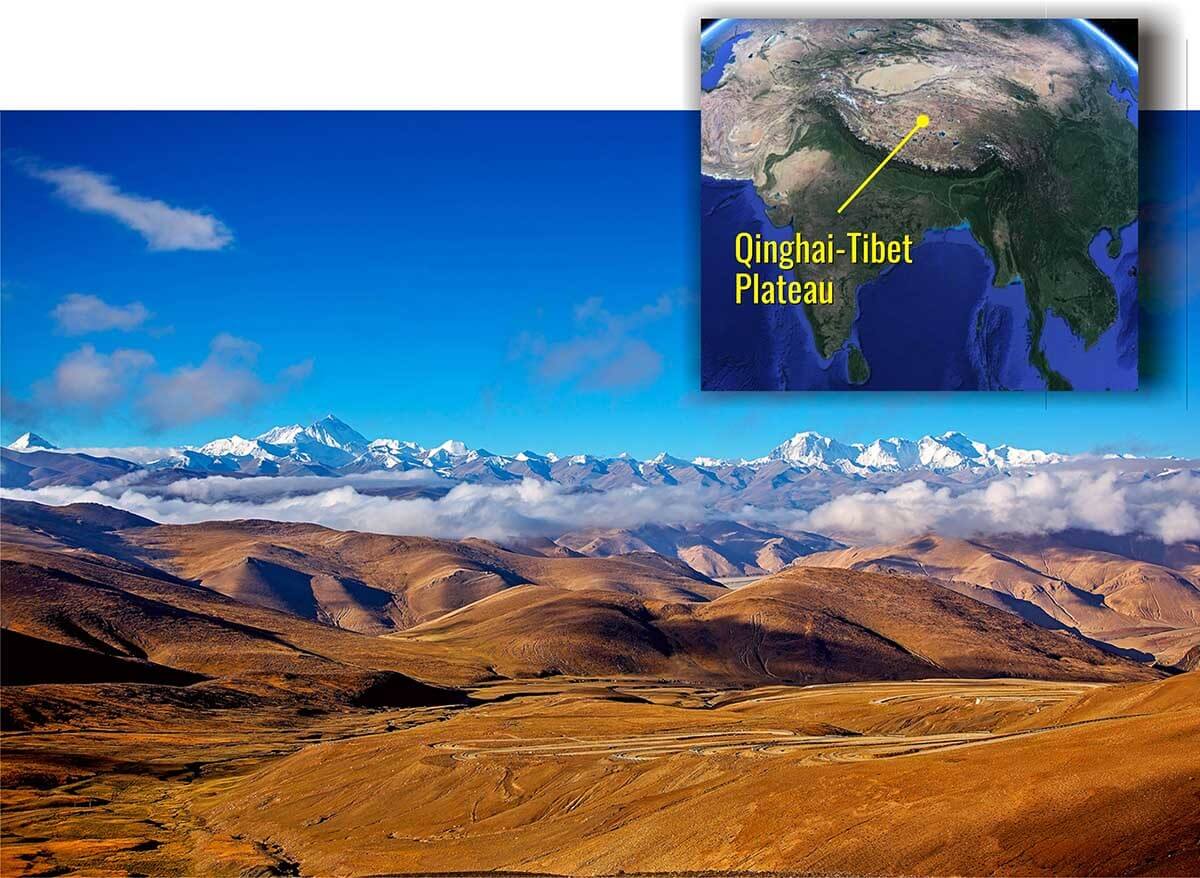

In the northern hemisphere, they include polar desert and semi-desert of the High Arctic, tundra, boreal forest, sub-arctic areas of maritime or continental nature, and Tibet’s vast high-elevation Qinghai-Xizang plateau. In the southern hemisphere, a similar map would include the higher elevations and southern tip of South America, the sub-antarctic islands, the Antarctic Peninsula, and the various ice-free zones on the Antarctic continent, namely the Dry Valleys.

The typical periglacial environment of a sub-antarctic island. Photo Renato R. Colucci

Indeed, there is no perfect spatial correlation between areas of intense frost and areas under permafrost. Several sub-arctic, maritime, and alpine locations experience recursive freeze-thaw oscillations but lack permafrost. Moreover, relict permafrost from the last ice age roughly ended 20 thousand years ago, underlies vast boreal forest areas in North America and Siberia.

In this view, any simple delimitation of periglacial environments is challenging. Nevertheless, using the diagnostic criteria above, a conservative estimation is that around 25% of the Earth’s land surface currently experiences periglacial conditions.

The boundary between periglacial and non-periglacial conditions is somewhat arbitrary and, to a large extent, varies according to different criteria. Indeed, no single climatic parameter adequately defines the limit of periglacial climates, though a mean annual air temperature of +3°C might be considered a good approximation.

Even within particular areas, there may be marked climatic variation relating to altitude, slope aspect, and distance from the coast. A fourfold classification of periglacial climates comprises high-arctic, low-arctic, and subarctic continental interiors, maritime periglacial with low annual temperature range, and alpine climates. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Antarctica do not fall readily into these classes.

An image of the Southern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau with Mount Everest in the background. Credits Dreamstime

High Arctic climates in polar latitudes show weak diurnal and strong seasonal patterns. Therefore, temperature shows a small daily and extensive annual range. Extremely low winter temperatures occur for several months when there is perpetual darkness, and the monthly average temperature may fall to -20 °C and -30 °C or even lower.

There are three key factors. The first is a strongly negative annual radiation budget at the top of the atmosphere in arctic areas. This equals roughly -60 to -120 Watts per square meter, implying that outward radiative losses exceed inputs. This is partly because north of 66.5 degrees, the Arctic Circle, there is complete darkness in winter, which becomes progressively longer with increasing latitude.

Global distribution of surface net radiation averaged from 2001 to 2015 from the CERES EBAF product.

A second key factor is developing a semi-permanent high-pressure system over much of the Arctic, especially between autumn and spring. This pattern prevents frontal systems incursions, thus limiting the associated movement of relatively warm and moist air into northern polar latitudes.

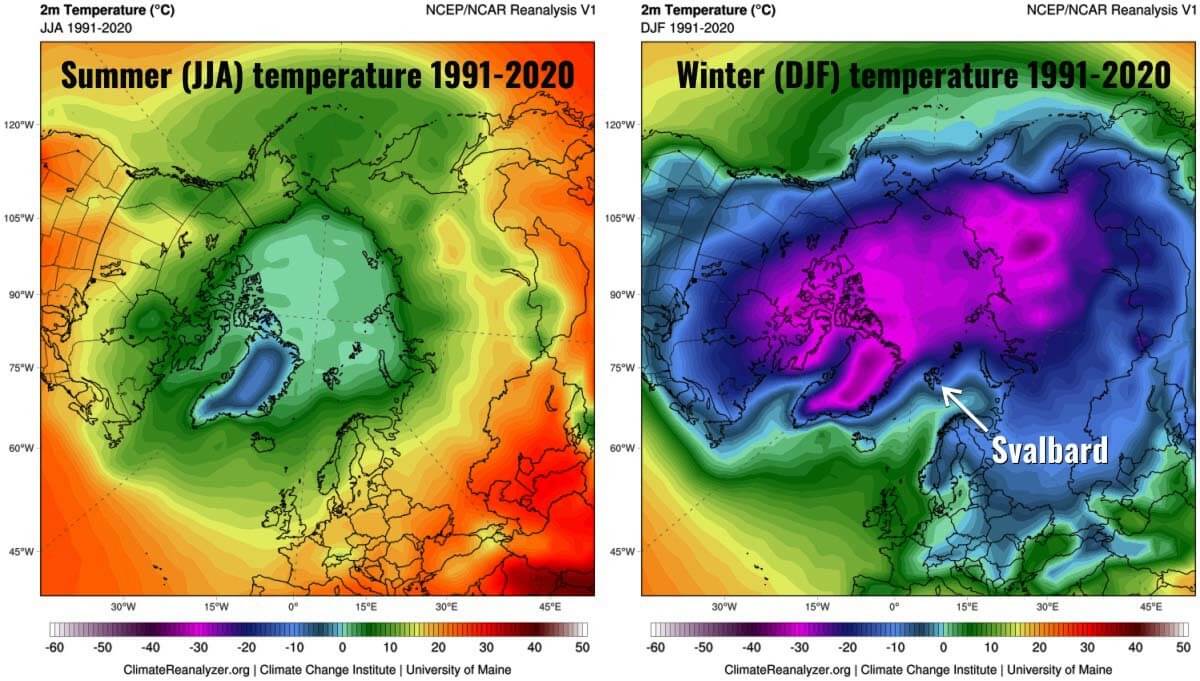

The North Atlantic cyclone track is the only exception. It extends eastwards from a zone of recursive low pressure called the Icelandic Low, centered south of Greenland at about 60 degrees latitude, and to a lesser extent, the Aleutian Low in the Pacific. The two lows of mean sea level pressure in the 1991-2020 winter map are highlighted in the image below.

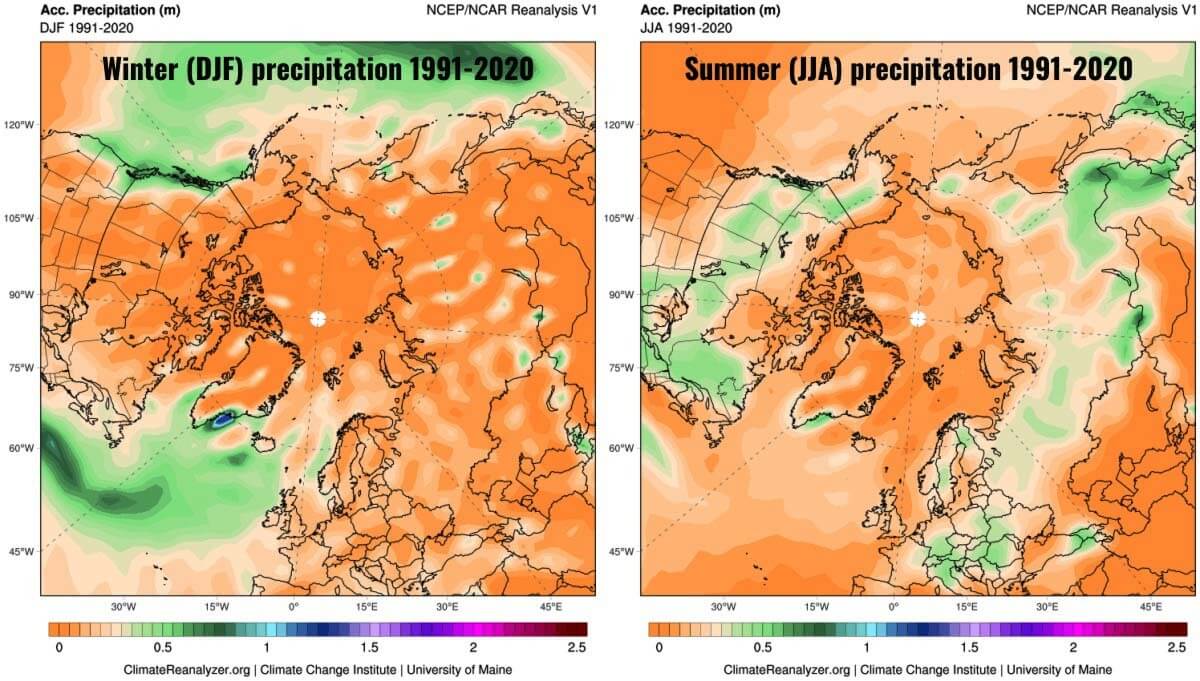

The most apparent effect of such a pattern is low mean annual precipitation in the Arctic. Extensive areas of the Arctic or sub-Arctic continental interiors have mean annual precipitation smaller than 400 millimeters of water equivalent (equal to liters per square meter). This is particularly the situation in the Canadian Arctic and northern Asia.

A belt of much higher precipitation with values greater than 600 millimeters of water equivalent interests Baffin Island across southern Greenland and Iceland into the Barents and Kara Seas. In southeastern Greenland, there is a sector with mean annual precipitation up to about 4 meters of water equivalent, likely the highest in the northern hemisphere. The map below shows the mean annual precipitation in meters averaged over 1991-2020.

The last of the three critical features in the Arctic is the heat transfer from the ocean, which reduces extreme temperatures in winter in surrounding landmasses. Heat loss to the Arctic Ocean also slightly depresses summer temperatures in coastal locations.

The map below with winter and summer average temperatures in the Arctic highlights the effect of the Arctic Ocean on the mean summer temperature of the Arctic coasts. Although summer is short (2-3 months) and relatively cool, with an average rarely greater than 5 degrees Celsius, a few summer days can be remarkably mild. Winter is milder in the North Atlantic sector of the Arctic, and Svalbard represents the warmest place in the Arctic, given the same latitude.

Low-arctic and subarctic continental interiors experience a much wider range of temperatures than High Arctic areas. The mean values disguise excessively low temperatures in winter and remarkably high temperatures in summer. Mean annual air temperature, in the end, is the same or slightly higher than in areas north of the treeline.

This temperature pattern reflects the absence of moderating oceanic influences. A high-pressure zone over eastern Eurasia builds during the autumn in response to radiative cooling and persists until spring. This is reflected in the lowest winter temperatures anywhere in the northern hemisphere.

As an example, Verkhoyansk, at 67 degrees latitude, has a mean temperature of -48 degrees Celsius in January and almost no precipitation, but for five months in the warm season, temperatures are above 0 degrees Celsius, peaking at 17 degrees Celsius in July.

Canadian locations like Churchill have similar if less extreme, characteristics with cold winters and moderately warm summers. On average, 4-5 months report a temperature higher than 0 degrees Celsius.

Where permafrost is present, warm summers allow seasonal thaw up to 2-3 meters deep, while seasonal ground freezing can reach similar depths where permafrost is absent. In the map below-average summer (JJA) and Winter (DJF) for Eurasia.

Precipitation in subarctic continental interiors is low and ranges from about 180 to 600 millimeters per year. Nevertheless, precipitation is more significant than in High Arctic regions because disturbances associated with the Arctic and polar fronts are more frequent at these latitudes.

Most precipitation falls in the form of rain and mainly during the summer. Nevertheless, the relatively high summer temperature promotes high evapotranspiration rates, so there is a seasonal soil moisture deficit. In the image below, higher summer precipitation between about latitudes 55 and 70 degrees North in contrast with high precipitation in the North Atlantic and North Pacific induced by the Icelandic and Aleutian Lows.

Maritime periglacial environments experience mean annual temperatures below +3 degrees Celsius and a low annual temperature range. Such climatic conditions occur in subarctic oceanic and alpine locations in low latitudes. Those areas are strongly influenced by the proximity of relatively warm oceanic waters and frequent cyclonic activity.

Extreme cold is generally absent, but precipitation is high due to frequent cloudy conditions and strong winds associated with deep depressions, especially in winter. Permafrost and deep seasonal ground freezing are usually absent, but ground-level air freeze-thaw cycles are frequent. Such temperature variability comes from the passage of alternating warm and cold air masses between autumn and spring.

As an example, such conditions are particularly evident in northwest Norway. Tromsø’s mean annual precipitation is slightly above 1000 millimeters, and the mean annual air temperature is 2.8 degrees Celsius. Much of Iceland experiences a climate similar to that of the south coasts of Alaska.

Other maritime periglacial conditions are typical of mountains in ocean-proximal locations such as southwest Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Scotland at elevations above 800 meters in the northern hemisphere. In the southern hemisphere, similar conditions are present in sub-antarctic islands such as Kerguelen, South Georgia, and the high ground in the Falkland Islands.

The maritime periglacial environment of South Georgia. Photo credits Renato R. Colucci

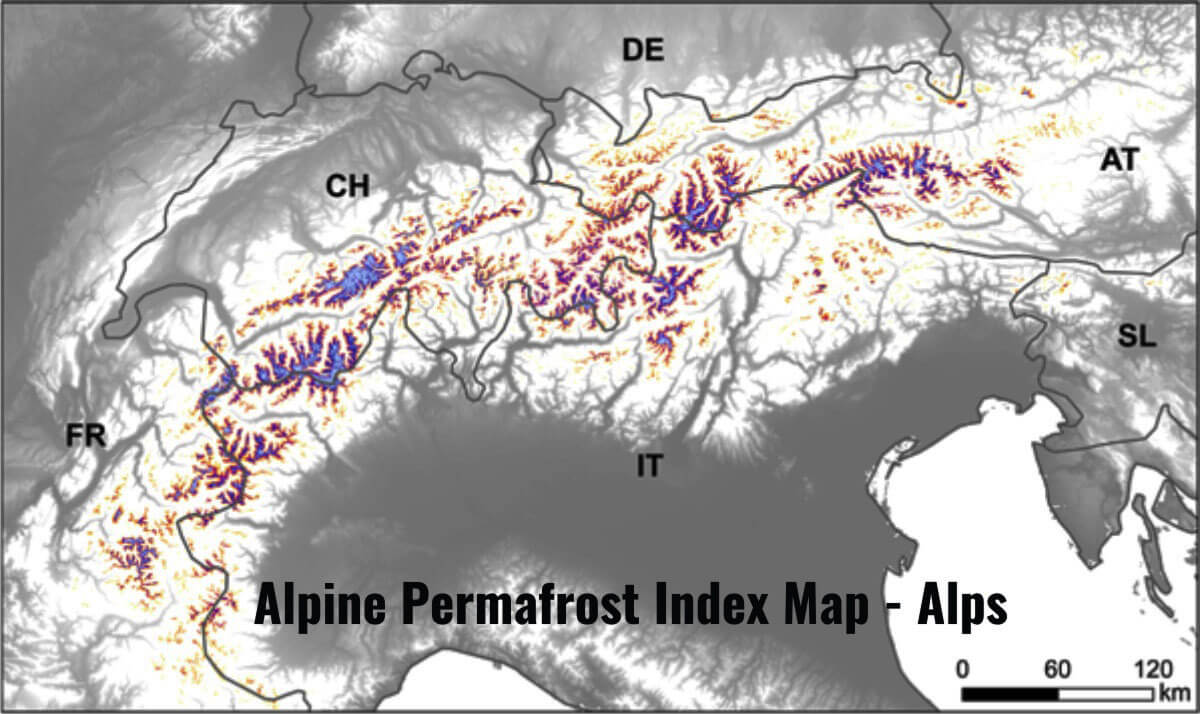

Alpine periglacial climates are those where altitude, slope aspects, and shading control the annual temperature cycle. They are not as extensive as any of the previous climatic environments. In the European Alps and North American Rockies, the timberline rises generally to a maximum altitude between 2000 and 4000 meters.

If the environmental lapse rate averages roughly 0.65 degrees Celsius in a stationary atmosphere every 100 meters, in practice, it may periodically and regionally reverse due to inversions. Precipitation tends to increase with altitude on mid-latitude mountains thanks to orographic processes. Air masses and frontal structures rise and cool adiabatically forced by the wind flowing against the massifs. This induces condensations, cloud formation, and orographically-enhanced precipitation. Conversely, compression and adiabatic warming give birth to dry föhn winds on the Lee sides, resulting in marked precipitation contrasts between the windward and Lee sides of mountain ranges.

Such difference is beautifully illustrated by the Southern Alps in New Zealand, as highlighted in the image above. Here, western windward slopes receive more than 6,000 millimeters of water equivalent of rainfalls, while eastern lee side slopes receive less than 1000 millimeters.

Permafrost is generally absent below the treeline in alpine areas but exists discontinuously at higher altitudes. Only on the higher summits and particularly on shaded slopes is permafrost continuous. The image below shows permafrost in the Alps according to the recently realized Alpine Permafrost Index map.

Antarctica and the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau are exceptional cases. In Antarctica, glacier ice covers more than 99% of the continent, and unglaciated areas are restricted to a few coastal areas, Transantarctic mountains, nunataks, and the dry valleys. A layer of extremely cold and dense air flows radially outwards from the Antarctic ice sheet, having a few hundreds of meters in thickness.

The cooling effect of winds blowing from the plateau results in mean summer temperatures between -5 and 0 degrees Celsius at the coastal margins and summer temperatures as low as between -20 and -30 degrees Celsius. For this reason, Permafrost is interesting in all free-of-ice terrain except a few coastal fringes of the Antarctic Peninsula.

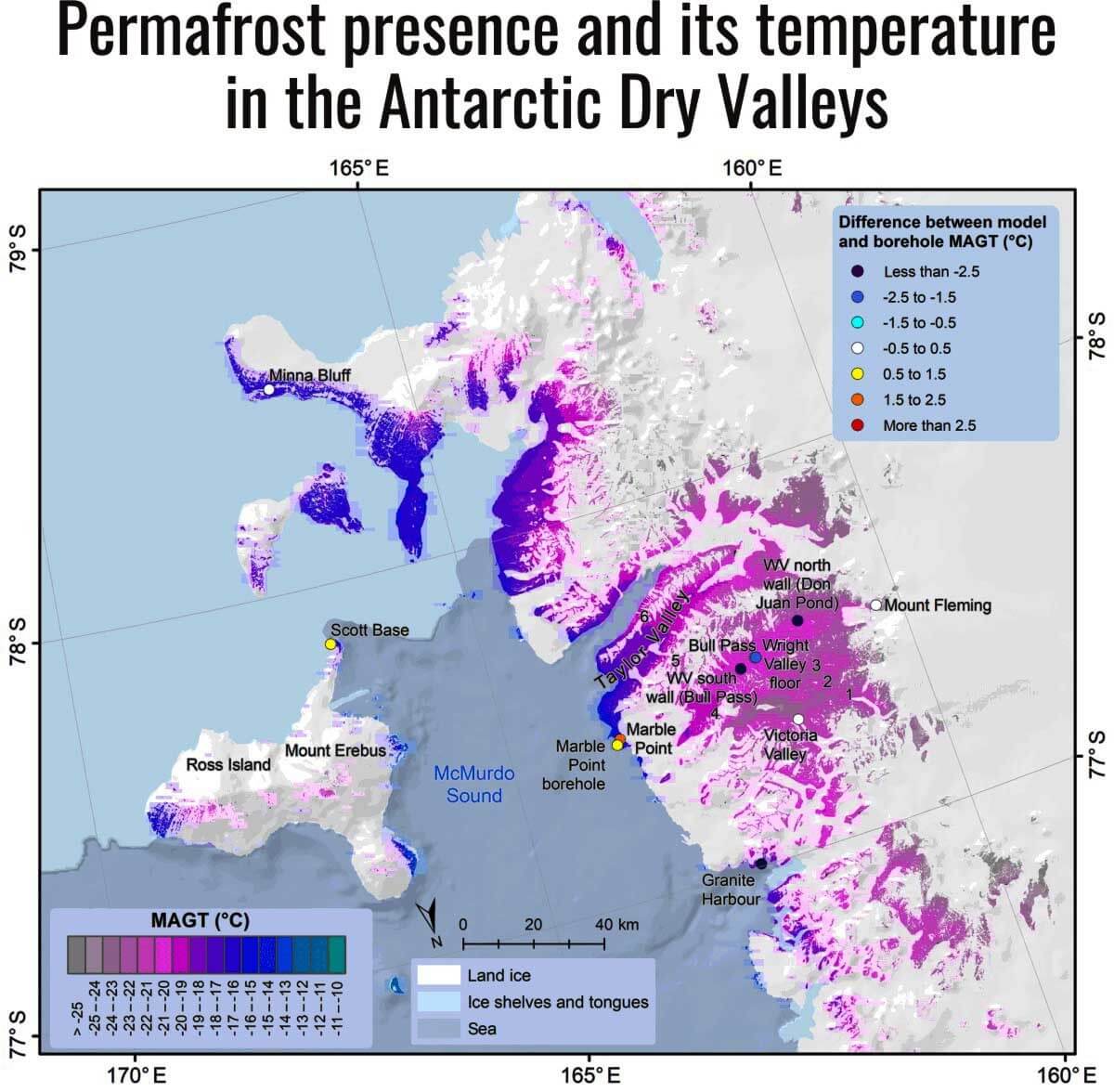

In the image above, permafrost temperature maps of the Transantarctic Mountains east of 90 degrees E, according to a recent paper by Jaroslav Obu et al.

The Transantarctic Mountains are the largest ice-free region and experience the harshest conditions thanks to their altitude and the impact of strong winds.

The region has numerous mountain ranges extending from the Ross Ice Shelf and the Ross Sea to more than 4000 m elevations and from 69 to 85 degrees S latitude. The Earth’s lowest permafrost temperature of −36 degrees Celsius is modeled at Mount Markham in the Queen Elizabeth Range.

Precipitation is very low and mainly falls in snow, although rain on coastal slopes can occur during incursions of summer weather systems from lower latitudes. An area of extreme aridity is the McMurdo Dry Valleys. This area occupies 4800 square kilometers in Victoria Land, and the mean annual air temperature ranges from -14.8 to -30 degrees Celsius.

A combination of low surface albedo, dry katabatic winds, and very low solid precipitation relative to potential evaporation make this one of the aridest parts of the Earth. Equally crucial in Antarctica is the exceptional strength and duration of wind. The station located on Inexpressible Island records near-continuous wind flowing outwards from the Priestley glacier at a speed of more than 50 kilometers per hour for over 51% of the time.

Permafrost zonation, permafrost extent, and the difference between the borehole and modeled MAGT for the Qinghai-Xizang (Tiber) plateau, according to a recent paper by Jaroslav Obu et al.

The Qubghai.Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau averages 4950 meters in altitude and has a low latitude between 29 and 37 degrees N. The mean annual air temperature ranges between -2.0 and -6.0 degrees Celsius. In contrast to the alpine environment, precipitation is low, similar to high latitudes, because the Himalayas act as a barrier to the deep penetration of moist air from the south.

Nevertheless, almost all precipitation falls between May and September. Continuous Permafrost is widespread, as it is visible in the image above.

So far, the best estimate of the permafrost area in the Northern Hemisphere is 13.9 million square kilometers representing the total area where the mean annual ground temperature is below 0 degrees Celsius. This extent corresponds to 14.6% of the exposed land area.

Average mean annual ground temperature for the Northern Hemisphere according to a recent paper by Jaroslav Obu et al.

PERMAFROST DEGRADATION

There is a lot of concern related to Permafrost degradation, mainly because massive positive feedback related to CO2 and Methane release in the atmosphere might eventually speed up Global Warming. As the global surface temperature has continued to rise over the recent decades, the risk of permafrost degradation has also increased.

The degradation of the permafrost may affect the climate system via many factors, such as local ecological balance, hydrological processes, energy exchange, the carbon cycle, the engineering infrastructure in cold regions, and even extreme weather events.

In other sections, We will discuss this and much more related to periglacial environments and permafrost. So bookmark our page to stay up-to-date with the latest educational articles on nature and weather in general.

See also: