The hurricane season 2021 has begun on June 1st, with the first-named storm Ana forming even before the official start. By Father’s Day coming up late this week, a tropical wave currently rolling over the western Gulf of Mexico could become Tropical Storm. It may meander north and reach the United States Gulf Coast in Texas or Louisiana. Another storm, Bill, is expected to form off the Atlantic Coast on Tuesday.

According to various sources, the Atlantic hurricane season 2021 is likely to be very active. Thinking just what has been achieved with the record-breaking season last year, hurricane preparedness is needed.

Just as we enter into the mid-June period, there are three tropical waves with a rising potential to become organized tropical disturbances this week. Storm Bill could be on the way along the Atlantic coast soon, followed by Tropical Storm Claudette near the Texas Gulf Coast towards the weekend.

The Colorado State University (CSU) team of scientists, led by Dr. Phil Klotzbach, calls for 18 named tropical cyclone formations, including 8 hurricanes and also the striking 4 major hurricanes for the Atlantic hurricane season 2021. The Weather Channel predicts 19 storms, NOAA’s CPC calls for 13-20 named storms this year.

Another, probably the most concerning part of the forecast for this year’s hurricane season is the almost 70% chance of a major hurricane landfall along the United States coastline. And nearly 60 percent for the Caribbean region.

The official Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1st through November 30th, although storms could also develop outside the official dates. Just like the first tropical system of the hurricane season 2021 did – Tropical Storm Ana formed on May 22nd, 10 days before the official start.

An average Atlantic hurricane season typically ends up with 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. It has two peaks, one in early/mid-September and another one in mid-October. Activity normally ramps up in August.

The Atlantic Basin covers the area which includes the entire Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea. The long-term average (taken over the last 70 years – between 1951 and 2019) of named storms is 11.

With the La Nina global weather pattern ending this spring, the tropical Pacific is now in a neutral phase. But well-above-average Atlantic sea temperatures, including the Caribbean and the Gulf temperatures, call for a busy hurricane season 2021. Neutral ENSO conditions should extend through the peak months (August to October).

Below is the video animation of the tropical Pacific and Atlantic sea temperature anomalies through the recent 30 days. It is an obvious sign that most of the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf are much warmer than normal. While the tropical central Pacific is reverting to neutral.

Note: For a tropical cyclone to strengthen into a hurricane, the weather conditions have to be just right. Normally, hurricanes form in low-shear environments with a lot of warm/hot sea waters which bring plenty of very moist air mass to fuel the convective storms.

DOUBLE TROUBLE IN THE ATLANTIC BASIN

With the hurricane season 2021 going into its third week after the official start on June 1st, there are now three (tropical) waves that have the potential to become better organized and possibly named storms in the coming days.

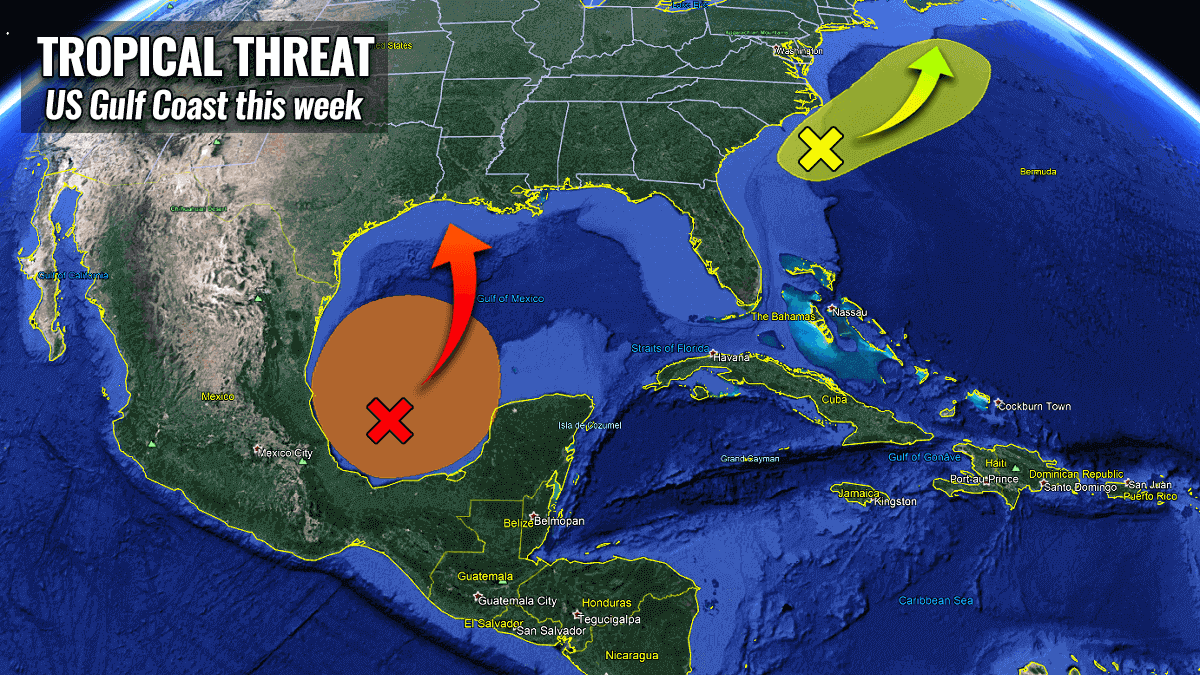

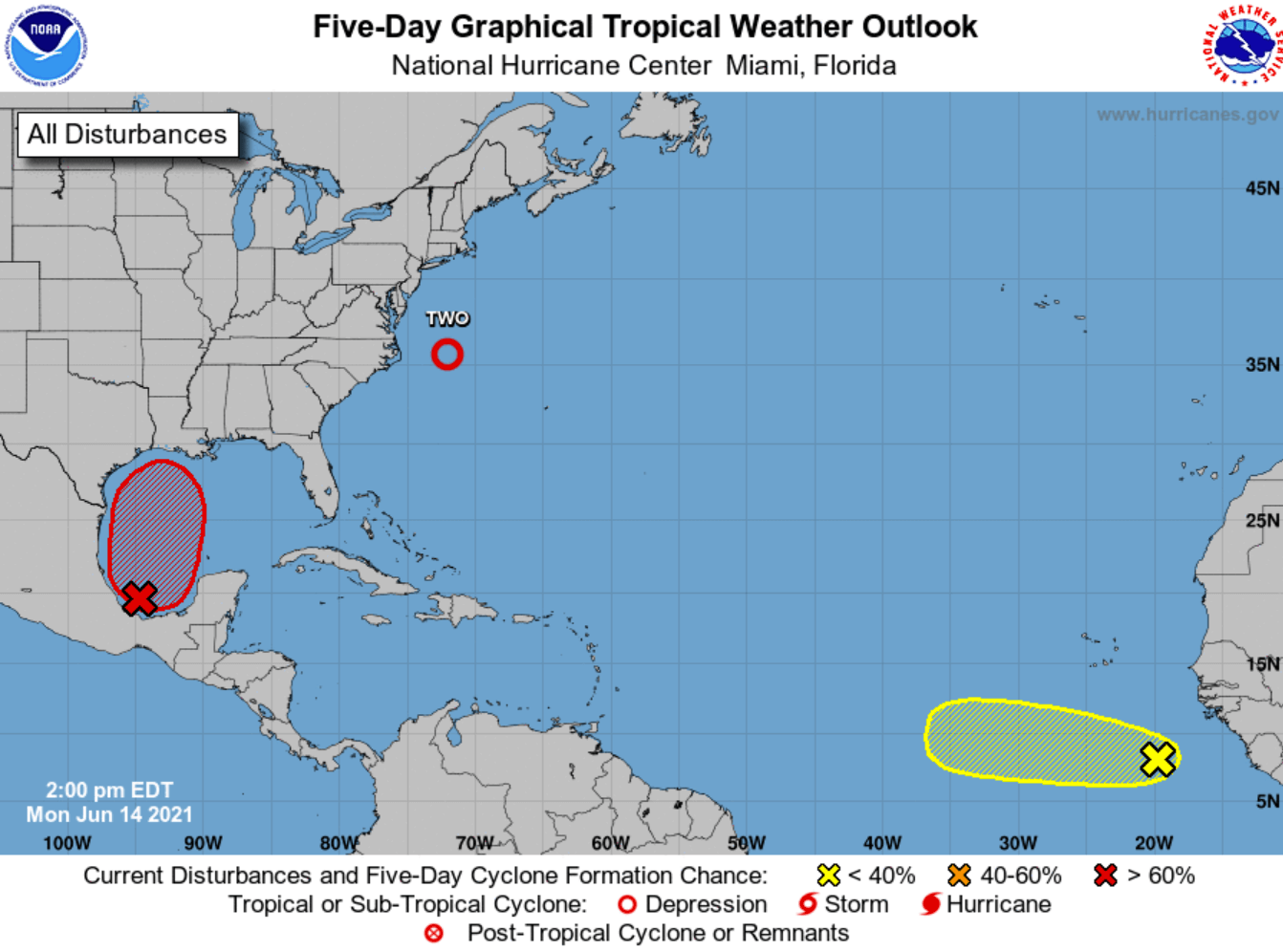

The first one is a large area of thunderstorms over the Bay of Campeche in the southwestern portions of the Gulf of Mexico. It is associated with a broad low-pressure area and is gradually beginning to organize.

The second area of interest is a low pressure, designated as tropical disturbance Two, around 150 miles east of the North Carolina coast, it is likely to become a Tropical Storm Bill over the next 24 hours. Bill is then expected to move towards the northeast while it meanders near the warm Gulf Stream waters.

It will be moving away from the United States, however, and gradually dissipate after Thursday.

The third is a strong tropical wave located south of the Cabo Verde Islands, having a large area of rather disorganized thunderstorm activity. Although there will be some development of this system possible in the coming days, a combination of dry air aloft and strong upper-level winds should limit further strengthening into a tropical system. There is only a 20% chance this wave becomes a storm by the weekend.

The Gulf low-pressure system could see further slow development over the next few days while the tropical wave will rotate near the coast of Mexico. Late this week, a tropical depression could form while the system would begin to slowly move northward towards the United States Gulf Coast (Texas and Louisiana).

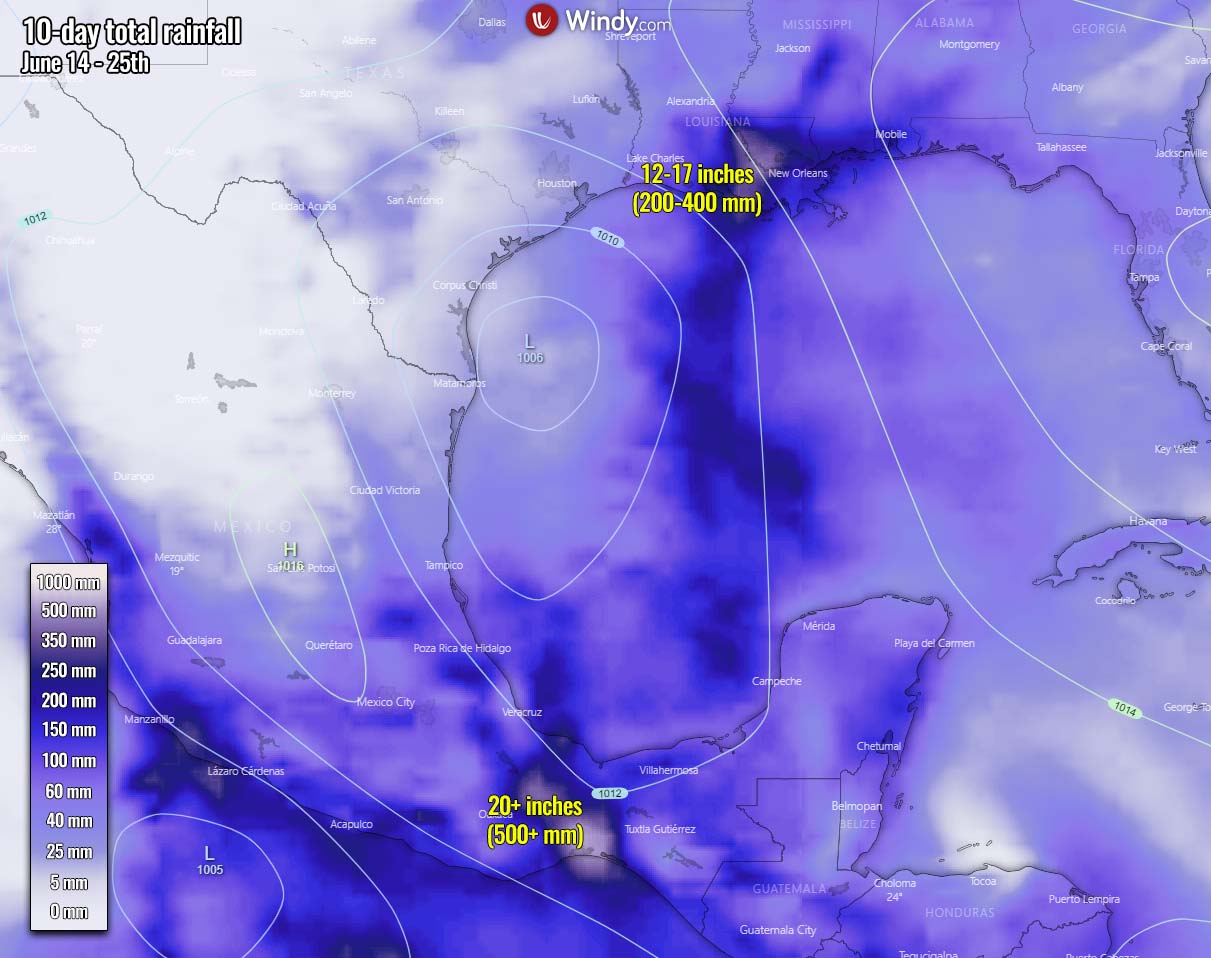

Heavy rains will gradually begin to impact portions of the northern Gulf Coast on Friday. Additionally, heavy rainfall and enhanced flooding potential will be possible over portions of Central America and southern Mexico this week.

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) is currently giving the Gulf wave a 20% chance to become a tropical depression over the next 48 hours and a 70% chance to become a named tropical storm over the next 5 days. The next name on the tropical cyclone names list is Claudette.

The tropical wave over the southwestern Gulf of Mexico needs to be closely monitored if it meanders towards the Texas coast around Father’s Day coming up next weekend. The European model ECMWF hints at some significant rainfall amounts for Louisiana.

About 12-17 inches (300-400 mm) of rain could be possible over the next 10 days. While another hotspot could be southern Mexico with more than 20 inches (500 mm) of rainfall simulated by the weather model.

If the Gulf wave finally is upgraded into a named system, it would be the very first system tropical storm to impact the United States this year. The location of this wave is actually very well placed with what is considered as statistically a typical June tropical cyclone formation in the western Atlantic Basin.

ATLANTIC BASIN WATERS ALREADY WARMER THAN AVERAGE

This June, the subtropical Atlantic is much warmer than normal and the tropical Atlantic is near average. The region with above-normal sea surface temperatures (SST) in the Atlantic has a pretty good correlation with what’s the typical June SST pattern when an above-normal hurricane seasons.

The tropical Atlantic Basin sea waters are pretty warm, ranging from around 27 °C in the central region, up to 29 °C across the western Caribbean, Similar temperatures, 28-29 °C are spread across the whole Gulf of Mexico, being the highest over the southwestern parts of the Gulf.

That is exactly where the focused tropical disturbance (possibly a storm Claudette) is developing, helping to fuel the convective storms with necessary very warm and moist air. Notice also very hot sea waters on the Pacific side, along western Mexico, reaching up to around 31 °C.

The sea surface temperature anomaly chart below indicates that the whole Atlantic basin, including the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, has water temperatures warmer than normal. Sea temperatures are especially anomalous across the western Gulf (marked as (1)), along the US East Coast, and further east across the Atlantic (2).

Notice also that the sea surface temperatures in the region known as MDR (Main Development Region – between Africa and the Caribbean Sea) are also quite warmer than normal. This hints at the potential that upcoming tropical cyclone formations will easily fuel from the very warm tropical Atlantic ocean waters.

Very high sea temperatures often lead to a rapid strengthening of tropical systems, better known as the rapid intensification process.

This spring, NOAA has officially declared that the La Nina global weather pattern has ended and the tropical central Pacific is now in a neutral phase. With the very warm and above normal seawater conditions expected to continue throughout this year, the neutral ENSO conditions will very likely boost the activity through the peak months of the hurricane season 2021.

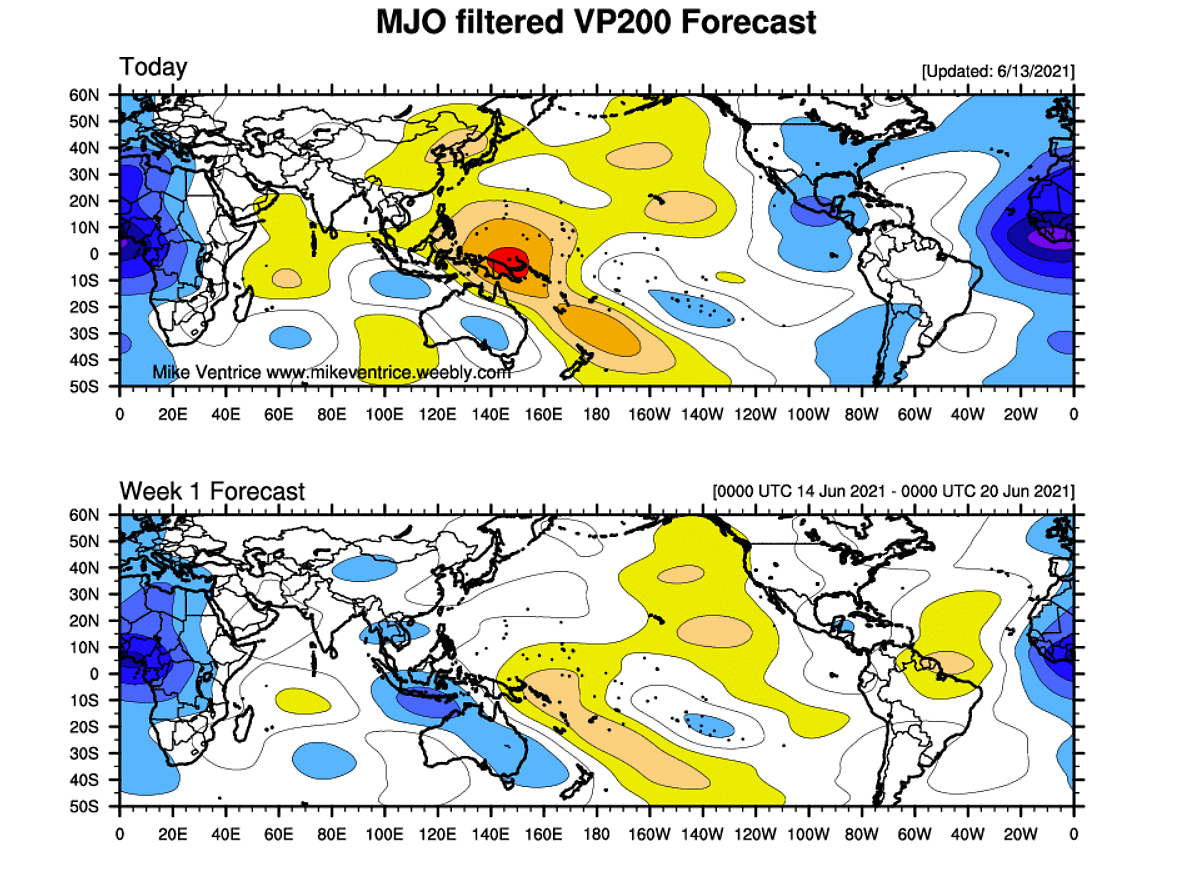

Besides the warm water temperatures, another factor is very important for the tropical cyclone formation. This is the so-called MJO wave. MJO is an abbreviation for the Madden-Julian Oscillation and is the largest and most dominant source of short-term tropical variability. It is an eastward-moving wave of thunderstorms that circles the entire planet on the equator in about 30 to 60 days.

WHAT IS THE MJO – THE MADDEN-JULIAN OSCILLATION?

The MJO wave has two parts, on one side it has an enhanced rainfall (known as the wet phase), and on the other side is the suppressed rainfall (therefore a dry phase). Simplified this means that there is an increased thunderstorm activity with a lot of rainfall on one side and reduced thunderstorm potential and drier (more stable) weather on the other side.

The wet phase leads to diverging flow, so the air parcels are rising (ascending) while the dry phase brings converging flow and therefore a descending air parcels. This horizontal movement of the air masses within the wave is referred to as the Velocity Potential (VP) in the tropics.

With the weather model data, we are able to perfectly track the entire MJO wave movement around the globe by looking at the larger scale air parcels movement. And we can easily see the areas where the air is rising and where it is subsiding.

The graphics below, provided by Michael J. Ventrice, Ph.D. represent an MJO wave with filtered VP200* anomalies (see details below) for the current state, and for the week 1 forecast.

The blue colors (cold) are representative of more favorable conditions for tropical cyclogenesis, e.g. across central America and the eastern Atlantic Ocean. While the red colors (warm) represent a less favorable state for tropical cyclogenesis, e.g. over the western and central Pacific Ocean on the chart above.

*VP200 indicates a Velocity Potential (VP). This is an indicator of the large-scale divergent flow in the upper levels over the tropics. The negative VP anomalies (shaded in blue colors) are closely related to the divergent outflow from enhanced convective regions.

As we can see, the current weekend’s VP200 analysis hints at quite favorable conditions over Central America with some remnants of blue colors also in the coming week. Therefore supporting some convective development and is why the potential for tropical disturbance seems possible over the Gulf of Mexico.

ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON 2021 FORECAST

The international committee of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has designated 21 storm names for the Atlantic hurricane season 2021. These are starting with Ana and ending with Wanda. The first storm Ana was already used before the official start of the season. The next storm would get a name, Bill, the third would be Claudette.

First, the Atlantic tropical cyclones had been named from lists originated by the National Hurricane Center, and are in use since 1953. Now, tropical cyclone names are maintained and updated by an international committee of the World Meteorological Organization. The hurricane name lists are used in rotation and re-cycled every 6 years. So the list which is in use this year will be used again in 2027.

With CSU predicting an above-average number of tropical storms and hurricanes this year, also the ACE is forecast to be very high. ACE is an abbreviation for the Accumulated Cyclone Energy – in other words, how much total energy storms produce.

According to dr. Phil Klotzbach, the Colorado State University (CSU) forecast calls for 18* named storms with the Atlantic hurricane season 2021. That is 25 percent (3.6 named storms) more than an average hurricane season. Note that the climatological data takes the latest 30-year period between 1991 and 2020.

The Weather Company (TWC) is forecasting 19 named storms, the United Kingdom’s Met Office (UKMO) about 14, while the NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center issued their forecasts predicting a 60% chance of above-average activity with 13-20 named storms, 6-10 hurricanes and 3-5 major hurricanes.

*Note that the very first named storm Ana is already included in those 18 named storms that are forecasted by the CSU experts.

As it can be seen, all the parameters that are typically monitored during a hurricane season are likely to be above average this year. CSU predicts about 80 named storm days (15 % above average), 8 hurricanes, and also 4 major hurricanes (25 % above average).

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) could end up around 150 which is about 22 % above the normal for the 1991-2020 period.

What is the ACE – Accumulated Cyclone Energy index?

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE index) is a metric that is used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. The calculated ACE value takes a tropical cyclone’s maximum sustained winds every six hours and multiplies it by itself to generate the values.

The total sum of these values is calculated to get the total for a storm and can either be divided by 10,000 to make them more manageable or added to other totals in order to work out a total for a particular group of storms.

The calculation was originally created by dr. William Gray and his associates at Colorado State University as the Hurricane Destruction Potential index, which took each hurricane’s maximum sustained winds above 65 knots (120 km/h = 75 mph) and multiplied it by itself every six hours.

The index was subsequently tweaked by the NOAA in 2000 that it now includes all tropical cyclones, with winds above 35 knots (65 km/h = 40 mph) and renamed to Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE).

Within the Atlantic Ocean, the NOAA uses the ACE index to classify hurricane season activity into four categories.

Extremely active – ACE index above 152.5

Above-average – ACE index above 111

Near-average – ACE index between 66 and 111

Below-normal – ACE index below 66

Note: the Atlantic hurricane season 2020 ended up at 184.5 ACE, so quite well above the threshold for the Extremely active category. This placed 2020 into the Top-10 Atlantic hurricane seasons based on the ACE index. The highest accumulated ACE during one hurricane season was in 1933, with an ACE of 259.

This particular hurricane season 1933 had 20 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and 6 major hurricanes. For instance, the hurricane season 2005 (the one with the 2nd highest number of named storms) produced 28 named storms, 15 hurricanes (record high), and 7 major hurricanes. 2005 had an ACE index of 250.

So as we can see, although the 1933 hurricane season had 8 fewer named storms and 4 fewer hurricanes than the 2005 season, their Accumulated Cyclone Energy wasn’t too far apart. So an extremely active season doesn’t necessarily mean the ACE would be off the charts as well. Long-lived hurricanes contribute to the ACE a lot.

If we just remember the hurricane season 2020, 30 named storms (record high), 14 hurricanes, and 7 major hurricanes, its total ACE index hasn’t come any near those to hurricane seasons 1933 or 2005.

NEUTRAL ENSO THROUGH THE PEAK OF THE HURRICANE SEASON 2021

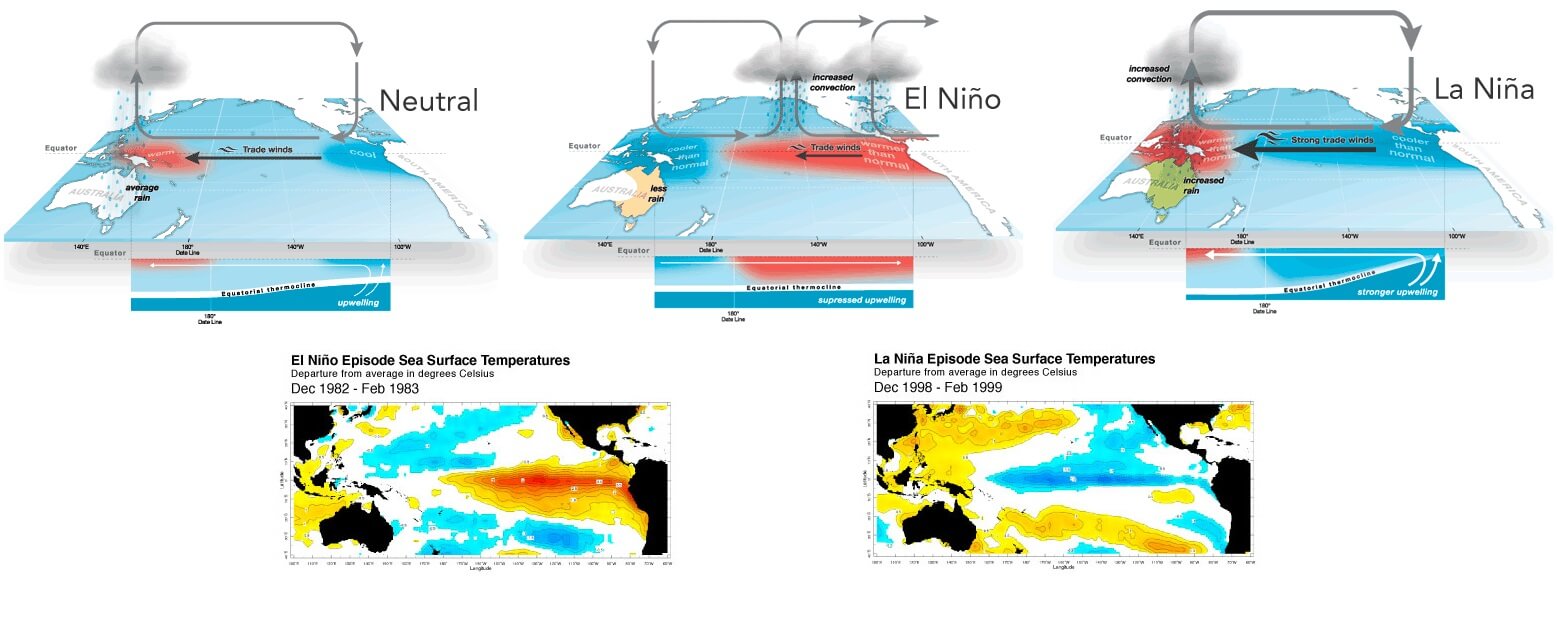

The ENSO, known as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation is a region in the eastern parts of the tropical Pacific ocean. It alternates between cold and warm phases. The easterly winds that circle the Earth near the equator (tropical trade winds), usually initiate or stop a certain phase, as they mix the ocean surface waters and alter the ocean currents.

The cold ENSO phase is called La Nina, while the warm phase is known as El Nino. Each ENSO phase has a different influence on tropical weather and how it impacts the weather worldwide. Speaking of the influence on hurricane season, La Nina usually boosts it, while El Nino keeps the activity lower.

La Nina normally means that the Atlantic hurricane season is well above normal, just as the 2020 hurricane season was. Last year was a textbook example of a strong La Nina (it was the strongest in the last 10 years) and very warm Atlantic sea temperatures throughout all year. An ideal recipe for wild tropical weather.

The latest probabilistic ENSO forecast issued by IRI continues to call for a very low chance of El Nino, but more than 55% chance of the neutral phase during the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. This peak is normally between August and October.

The Pacific Ocean is forecast to continue warming up into normal sea temperatures over the next few months, so the ENSO circulation is expected to remain neutral.

According to NOAA, El Nino is not expected to arrive until probably the end of 2021 or even early next year. So the peak of the hurricane season 2021 will take advantage of the neutral conditions, meaning busy months ahead.

The lack of El Nino is surely a great concern, as forecast numbers are calling the well-above-average to potentially even extremely active Atlantic hurricane season 2021. After record-breaking 2020, this is not a good sign at all.

Our team will be actively following the tropical region worldwide, so stay tuned for further follow-up posts, forecast discussions, and nowcasting during the coming weeks and throughout the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season 2021.

***The images used in this article were provided by Wxcharts, Tropical Tidbits, and Windy.