Here is the annual Lyrid meteor shower 2021! The peak activity is tonight and also the next night, so many of us will be out under the skies observing this fine celestial show. Depending on the weather conditions, of course. Learn how to observe and photograph meteors.

This year, the shining waxing gibbous moon will limit the observations until the final hours of the night, as the moon will set at around 4 a.m. The viewing of the Lyrids will be less favorable than last year. Still, there are great chances for many observers across both continents

However, at that time, the constellation of Lyra and its brightest star Vega are very high in the sky. So at least for about an hour, you will have proper dark skies bad very good observing conditions. After about 5 a.m., skies begin to brighten as sunrise is quickly approaching.

We will take a detailed look how is the weather forecast across Europe and the United States for the Lyrid meteor shower 2021. We will also guide you through the background of the Lyrid meteor shower and how to find them in the sky, and how to dig in into meteor photography.

WHAT IS THE LYRID METEOR SHOWER

The first burst of meteors in the spring is the Lyrid meteor shower, peaking around April 21st or 22nd every year. The Lyrids are a moderately strong shower with up to around 15 to 20 meteors per hour under favorable observing conditions and a dark sky.

The Lyrid meteor shower radiant is halfway between the constellations Lyra and Hercules, so it is first low in the eastern sky in the evening hours but rises quite high into the pre-dawn hours.

The Lyrids are actually the legacy of a long-departed comet, known as the comet Thatcher. This comet was discovered in April 1861 by an amateur astronomer, A.E. Thatcher, with an orbital period of about 415 years. And the Earth’s orbit meets with the comet dust particles around April 22nd each year.

The historic record is spotted with strong returns of the Lyrid meteor shower. As far back as 687 B.C., Chinese astronomers spotted a strong return of the Lyrids. Additional strong showers were seen in 15 B.C. and 1136 A.D. when Korean chronicles note that ‘many stars flew from the northeast.

But the first well-observed Lyrid meteor shower outburst was in 1803. According to the reports, there were so many Lyrids that the people of Richmond, Virginia were alarmed at the spectacle unfolding in the sky. As many as 500-1000 meteors per hour could be seen. That is about ten times as strong as the typical Perseid meteor shower activity. Additional strong returns with more than 100 meteors per hour were also seen in 1922, 1945, and 1982.

HOW TO SPOT THE LYRIDS?

Place yourself in a dark sky away from light pollution. Lyrid meteors will appear originating from the area in the sky, known as the meteor shower’s radiant, will be in the northeast part of the sky after sunset and almost directly overhead in the hours before dawn.

It is easy to find the Lyrid radiant. After twilight look towards the east. The brightest white star in that part of the sky is Vega, the brightest star of constellation Lyra. The radiant will be some 10° higher up – make a fist and extend your hand – the radiant is one width of your fist above Vega. The Lyrids can appear anywhere in the sky, but if you backtrack their paths, all will converge in the radiant.

The Lyrid meteor shower does not have a rich display, especially if we compare it with the Geminid meteor shower in December or the Perseid meteor shower in August. The Lyrids are medium-fast meteors, quite slower than the popular summer Perseids. Some of these meteors tend to be quite bright and about a quarter of them leave a trail that can persist for quite a few seconds.

Observing tip: Once you have located the radiant, you don’t want to just stare at that spot all night. Longer streaks tend to appear farther from the shower’s radiant, so you might miss the best meteors if your eyes are focused on that singular spot all night. Get in a comfortable spot and observe a large part of the sky around the radiant point in the Lyra constellation.

If you live in the Southern Hemisphere and want to observe the Lyrid meteor shower, here is some tip. As the Lyrid’s radiant point is so far north on the sky, the star Vega rises only in the final night hours before dawn. so the constellation Lyra will be much lower in the sky than for the observers in the Northern Hemisphere. But you should still see a few Lyrid meteors on those pre-dawn hours.

HOW TO PHOTOGRAPH THE LYRID METEOR SHOWER – METEOR PHOTOGRAPHY

Lyrid meteor shower photography (or any other meteor showers) can be loads of fun and with a bit of luck, you can catch a bright one, known as a fireball! Here are some tips and tricks on how you can do it.

First of all, the best is to have a camera with the option of making long exposures. Any interchangeable lens camera (DSLR or mirrorless) will have this option, but also many compact cameras and some phone cameras have the long exposure option.

Then you need a remote trigger for the camera (or timer) and place your camera on the sturdy tripod. And of course. You need a meteor shower. The stronger it is, the better results and catches you could potentially achieve.

How to do the meteor photography – Camera settings:

The best time to photograph meteors is during a maximum of major meteor showers, known as the meteor shower peak. The greatest chance is with the most recognized and active meteor showers, such as the Quadrantids, Perseids, and Geminids. But you can also be quite successful with moderately strong meteor showers, such as the Lyrids, Southern Delta Aquarids, Orionids, Taurids, Leonids, and Ursids.

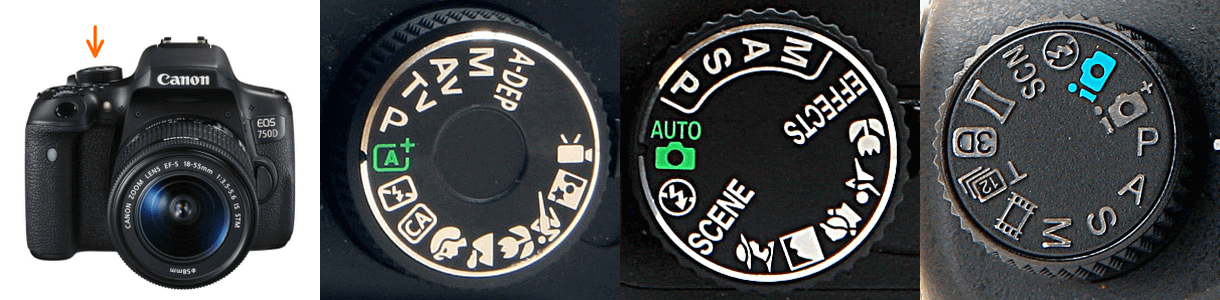

When photographing meteors avoid using Auto and preset scene modes. You need to be in control of the camera. Set the mode too long exposure. There are several ways about it and they may vary depending on your camera brand. One of these is the M – Manual. Some cameras may have B – Bulb mode. This mode allows you to use a remote trigger to do exposures of any length.

The other mode that is useful is the shutter priority mode (Tv or S). With this model, you can select the exposure time for your photo. All interchangeable lens cameras have these modes, regardless of the brand – Canon, Nikon, Pentax, Sony or any other, you will be fine.

Use sufficiently high ISO setting to capture meteors, 1600 or more will be good. How far up the ISO scale you want to go indeed strongly depends mostly on your tolerance for noise. And of course how good ISO performance your camera has.

How to do meteor photography – choosing the proper lens:

Virtually any wide-field or standard lenses on the market will do fine, so will any mid-range zoom lens. Most entry and up to prosumer crop sensor (DX or APS-C) cameras come with mid-range kit zoom lenses, which are usually between 16 and 18 mm at the wide end and f/2.8 to f/4. These are solid lenses for meteor photography.

So the standard 50 mm lenses are fine too, usually being wide open e.g. f/1.4 to f/1.8, so they gather a lot of light and can help you to capture fainter meteors than mid-range zoom lenses. The downside of these lenses is the small field of view, particularly if you use those on crop sensor cameras.

50 mm will be your limit your focal length, so avoid using even longer focal lengths as the field of view becomes too small. Unless you plan to take advantage of your pure luck and point the camera into a known deep-sky object, e.g. Orion nebula, M31 Andromeda Galaxy, Pleiades, etc. It could be a fine composition if you are lucky to get a bright meteor (fireball) into that narrow field.

Here is an example of the Perseid meteor shower composite, taken over the city of Rijeka, Croatia during the peak in 2019. Photographed from mt. Ucka nearby, with 24 mm lens. Photograph by Marko Korošec

As we can see from the sample image above, the best lenses for meteor shower photography are the wide-field lenses with maximum aperture f/1.4 to f/2.0, available from several brands (Samyang, Rokinon, or Sigma Art).

When you are out in the field, prepare the camera (mounted on the tripod), and make sure the camera is leveled. Look through the viewfinder and make sure the horizon is at a good level. Then focus on the lens. The easiest way to do it is to set it to manual focus and focus it on a distant light or a star. Use live view (with maximum magnification) for optimally doing this.

Once you have the focus done, keep the lens in manual focus mode to avoid the camera refocusing. Set the aperture to fully open and the ISO and you are ready to go. Be ready to shoot *many* photos before catching the first good meteor, but the more persistent you are, the more likely you are to catch a bright one!

How to do meteor photography – additional tips:

Here are some additional tips that could help you fine-tune your meteor photography skills and give you better results.

When you shoot the meteors, don’t get the background too bright, as you want good contrast between the sky and meteors. Typically a histogram with a peak around 1/8 to 1/6 full (left to right) is considered optimal. This will indeed depend on the lens you use, ISO setting, and how dark your sky at that location is. That’s why it is your goal to get to the darkest location possible, away from the city lights and pollution.

Fast lenses and high ISO settings will get your background bright pretty fast. So a bright, light-polluted sky will also get the background bright faster. An f/2.8 lens at ISO 3200 under a good rural sky will only take about 20 seconds to hit the limit.

Very fast lenses, f/1.2 to f/1.8 will produce the best results under (very) dark skies. Brighter, light-polluted skies will saturate the background quickly and ruin the good contrast you want to achieve with meteors.

But do not use too short exposures. As the shorter you go, the more likely you are to get a ruined photo by ending the exposure in the middle of a bright meteor. Or even miss them as they shoot right at the time when they occur. This can be extremely frustrating. With a 10-second exposure, you will probably ruin 5-10% of meteors, so keep the shooting exposure of at least 15 seconds or more.

Don’t forget to turn off your High ISO noise reduction. You can do noise reduction in post-processing. Also, turn off your Long exposure noise reduction. At this setting the camera makes a dark exposure for every photo you make – you will only photograph the sky for 50% of the time, missing half the meteors. There are few things as frustrating as missing a superb meteor while your camera is making a dark exposure.

Shoot in RAW format, or RAW + JPEG. It pays off to have a RAW photo to edit later. So any details can be taken out of the RAW file pretty easily in the post-processing procedure.

Keep your white balance on AUTO. It typically works best. You may want to change to a warmer setting (some astrophotographers prefer 3700 K) under light-polluted skies, if there is variable cloud cover and the clouds are illuminated by light pollution or if your camera is having trouble keeping the white balance constant. but it is best to shoot in RAW format as you can correct white balance in post-processing.

This has to be repeated, as was mentioned earlier. Use Live View and a bright star or very distant light source to focus your photo. Make absolutely sure your focus is dead on. There are few things as frustrating as out-of-focus photos of bright meteors. Keep your camera and lens in manual focus mode, otherwise, it will try to refocus once you start your exposures and your photos will be out of focus.

Now, let’s take a look over the cloud coverage in the low/mid-level height which is the best level we normally look for when forecasting the potential for clear skies. Although high clouds matter too, at least bright meteors are still visible through the high clouds. While the low/mid-level clouds completely obscure the meteors and night sky.

Remember, the best times for observing are from 10 pm local time until about 5 am local time.

CLOUD COVERAGE ACROSS EUROPE

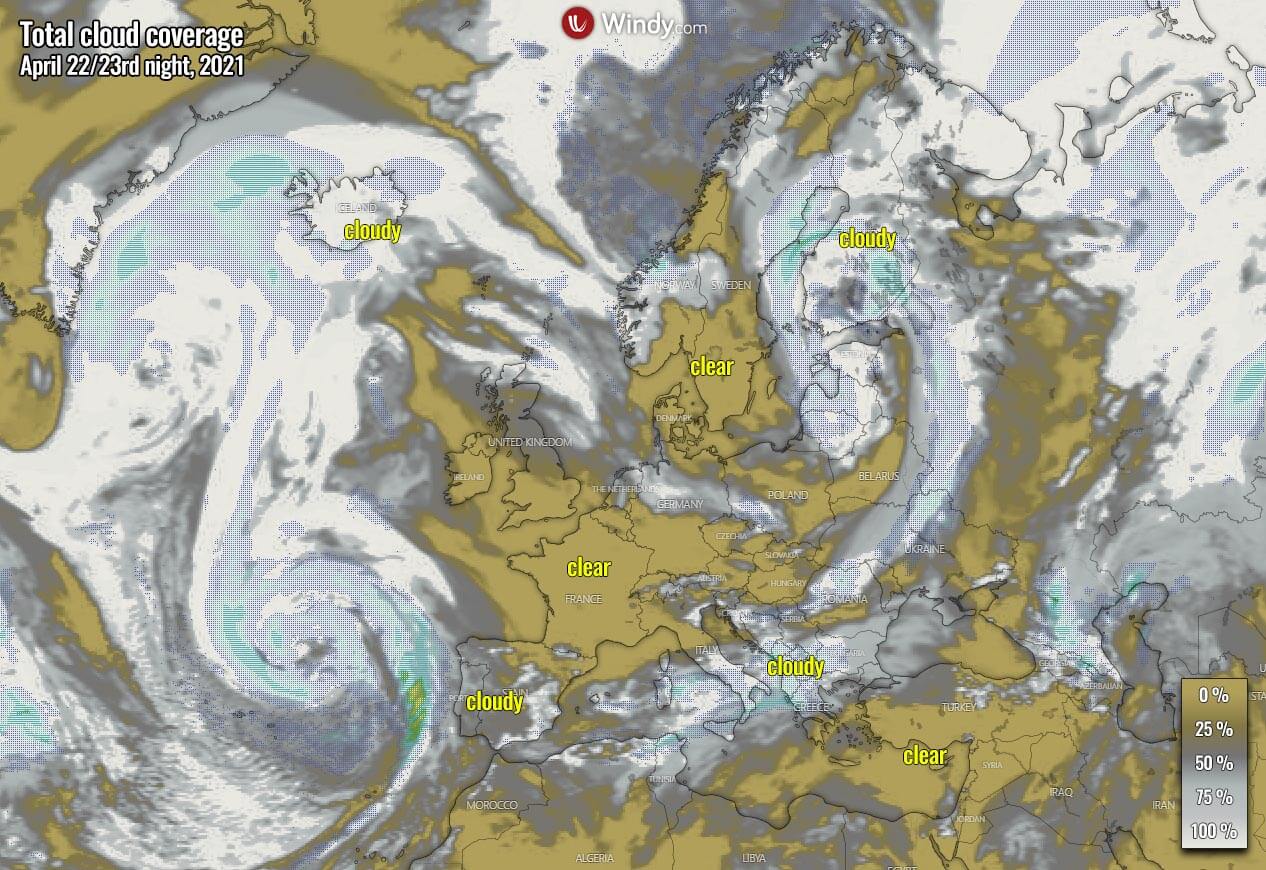

The general weather pattern across Europe hints at a deep trough and low-pressure system across northern Europe and southwest parts, while high-pressure systems are expanded across western, central, and southeast Europe. This will help the nighttime hours to become clear for some observers.

If we take a look at the total cloud coverage tonight, from Apr 21st to 22nd, there will be clear skies across parts of Ireland and the southern UK, a large part of France, possibly over central Europe. Better conditions seem across the Balkans, Turkey, and the eastern Mediterranean.

Thanks to the cyclonic systems over Scandinavia and southwest Europe, clouds will be quite an issue across Portugal, Spain, and the west-central Mediterranean. Also across most of Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

It will be cloudy across Iceland, the Netherlands, Italy, and the western Balkans. These areas unfortunately don’t have many chances to observe the Lyrid meteor shower tonight.

But if we take a look also what is up for the next night, April 22nd to 23rd, conditions seem to improve quite well across the west and central parts of Europe. Modeled total cloud coverage hints at clear skies and great observations across southern UK and Ireland, France, Benelux, most of central Europe. Also across southern Scandinavia.

While clouds will obscure the observations across Portugal and most of Spain again, also across the west-central Mediterranean and the south-central Balkan peninsula. It will remain quite clear across Turkey.

CLOUD COVERAGE ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

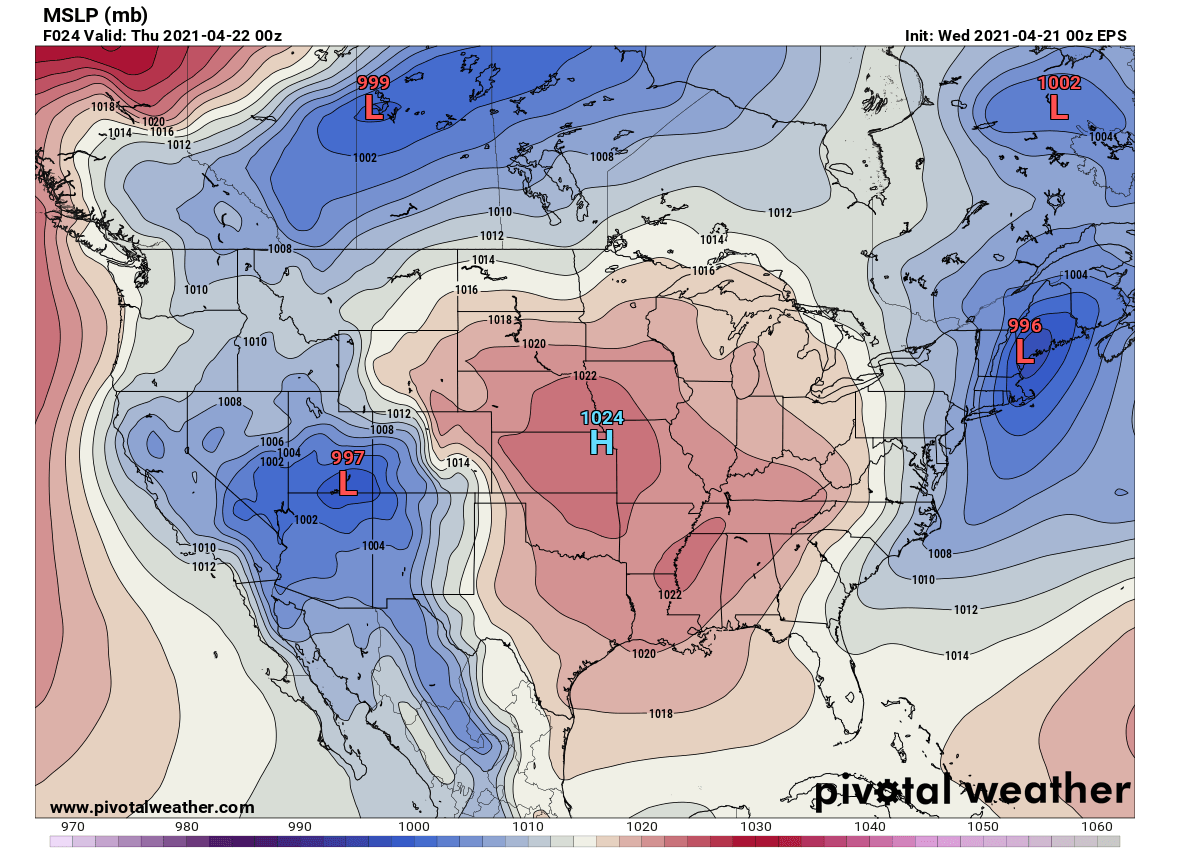

The general pattern across the United States through this mid-week reveals a deep through moving towards the Northeast parts of the country, with a surface high-pressure developing in its wake. This will bring colder nights, but those will be mostly clear for many.

The further west, low-pressure system extends across the west-southwest portions of the U.S.

The total cloud coverage forecast for tonight, April 21st to 22nd calls for very good observations across most of the North, Southeast, and also the Southwest United States. A help from northerly winds in the wake of the deep East Coast will also bring crispy clear air mass between the Upper Midwest to Florida.

Some clouds are likely across the southern and central (High) Plains, thanks to the return southwesterly flow in response to the lower pressure across the Southwest. And indeed a lot of clouds remain with the frontal system across the Northeast United States.

The weather conditions will be a bit worse for the next night, which should still bring some fairly good number of Lyrid meteors. It will remain clear across the Southwest and parts of the northern High Plains, and significantly improve across the East Coast and the Northeast as the frontal system ejects off to the east.

Cloudiness will increase across the central parts of the U.S., thanks to the intensifying frontal system towards the Great Plains. Clouds will cover Midwest, the Mississippi Valley, and the Deep South. Another cold front will also cover Montana and the far North.

Good luck with your observations and feel free to report us via our social media channels or E-mail.

***The images used in this article were provided by Pivotalweather, and Windy.

Don’t forget to bookmark our page to have all the new info ready at hand. Make sure to bookmark our page, or click on ‘show more‘ if you are reading this article from the Google Discover feed.