A smaller-scale lava eruption continues in Iceland, with little harm outside the eruption area. But a much larger volcano is currently getting close to an eruption in Iceland. It is a much more violent, explosive volcano, with historical impacts on life in Europe and the Northern Hemisphere.

The volcano in question is called Grimsvotn, currently the main candidate for the next larger explosive eruption in Iceland. And it is likely not too far away from starting one.

WHERE FIRE MEETS ICE

Iceland is a volcanic island in the North Atlantic. It is one of the most active volcanic regions in the world. As history shows, its eruptions can sometimes have powerful impacts on Europe, North America, and the entire Northern Hemisphere.

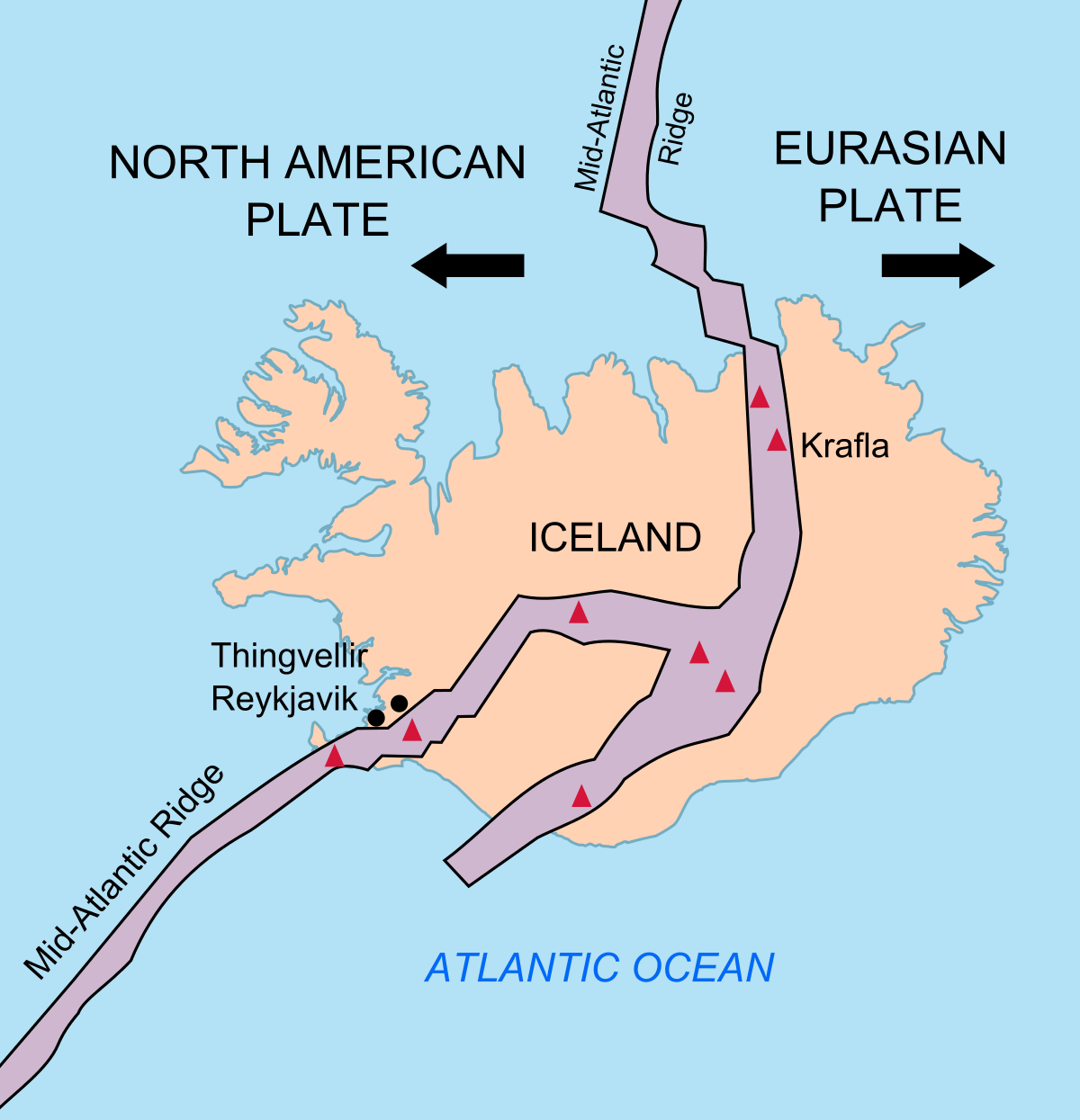

The island experiences constant earthquake activity because it sits on the boundary between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. This boundary is also known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR). The plates are moving away from each other, tearing the island apart. It is the only place in the world where the Mid-Atlantic Ridge rises above the ocean surface.

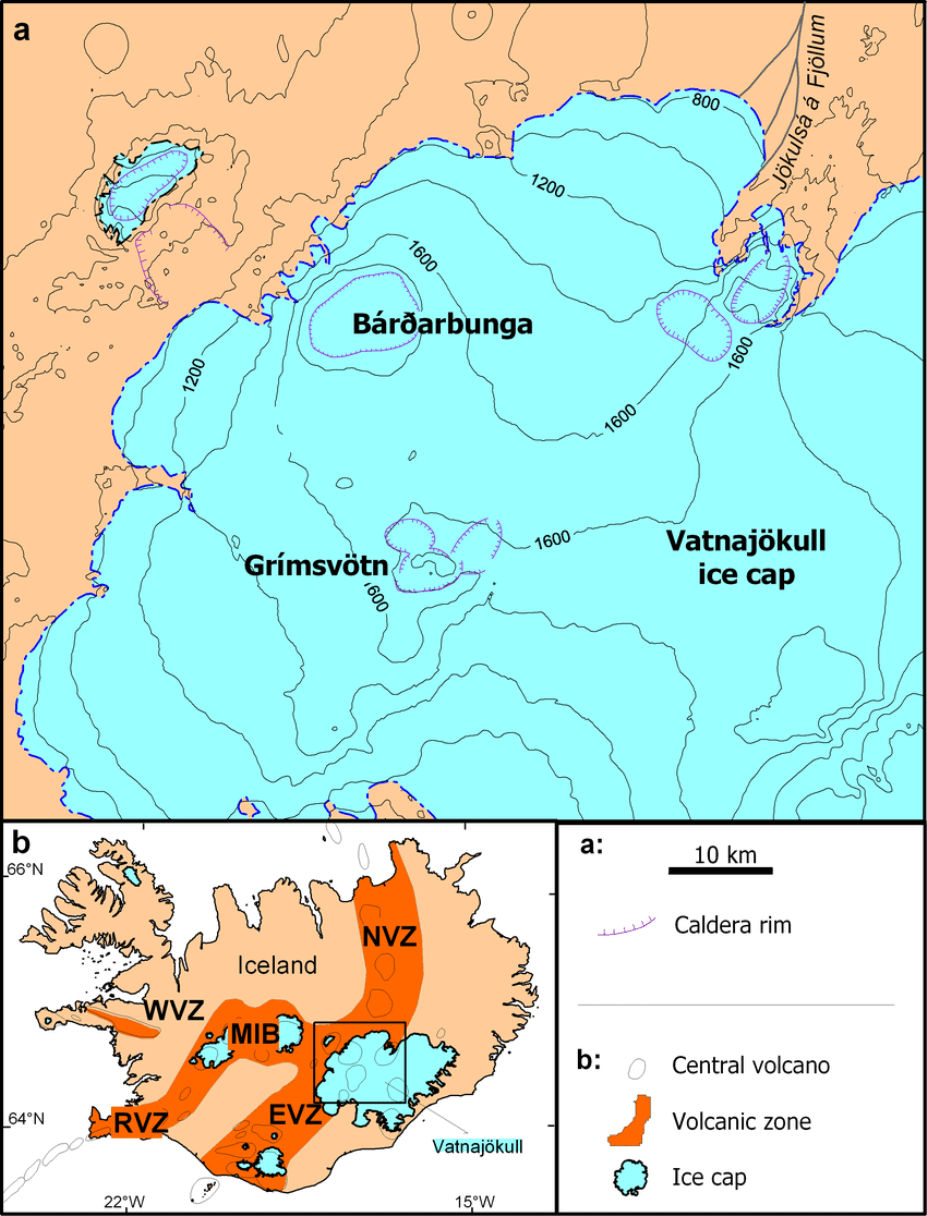

On the image below, you can see where the spreading tectonic plates and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge pass through Iceland. It enters in the southwest on the Reykjanes Peninsula, going towards the east, where it then turns north. Main volcanoes are marked in red.

We produced a high-resolution video, which shows the daily earthquake locations in Iceland since January 2019. You can nicely see main earthquake activity is exactly on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge across Iceland, having constant daily activity.

But the tectonic plates spread apart across the entire Atlantic Ocean. So why is this location so special, that produced a large island over the millions of years?

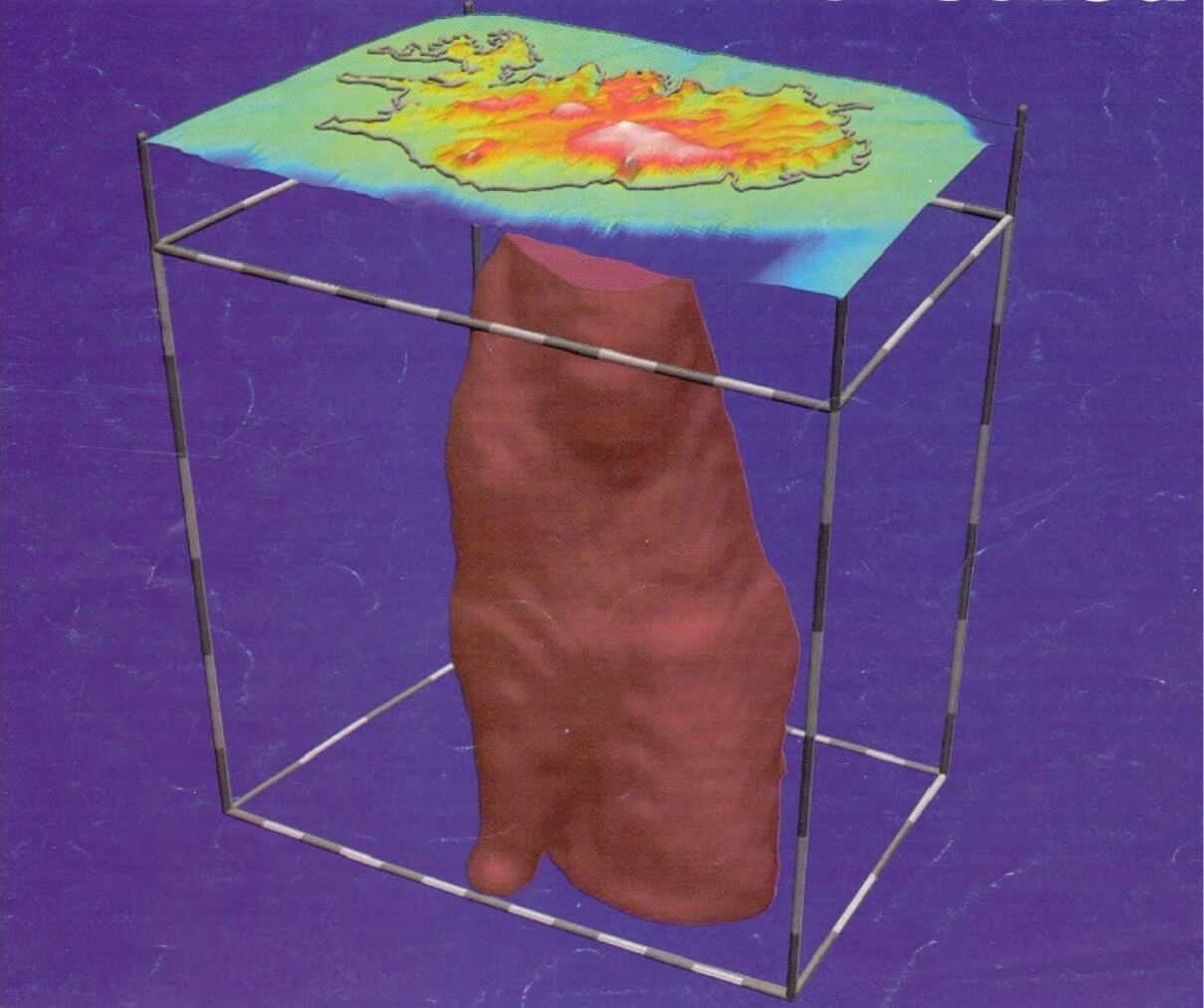

The answer is a vertical plume of hot molten rock from the mantle, also called a hotspot, that lies beneath Iceland (similar to the hotspot under Hawaii). It is more commonly called the Iceland plume. The image below is a graphical presentation of the rising mantle plume beneath Iceland.

The high-pressure magma from the depths of the Earth has found its way to the surface. Following the path of least resistance, it pushed through the cracks between the spreading tectonic plates, starting to build an island.

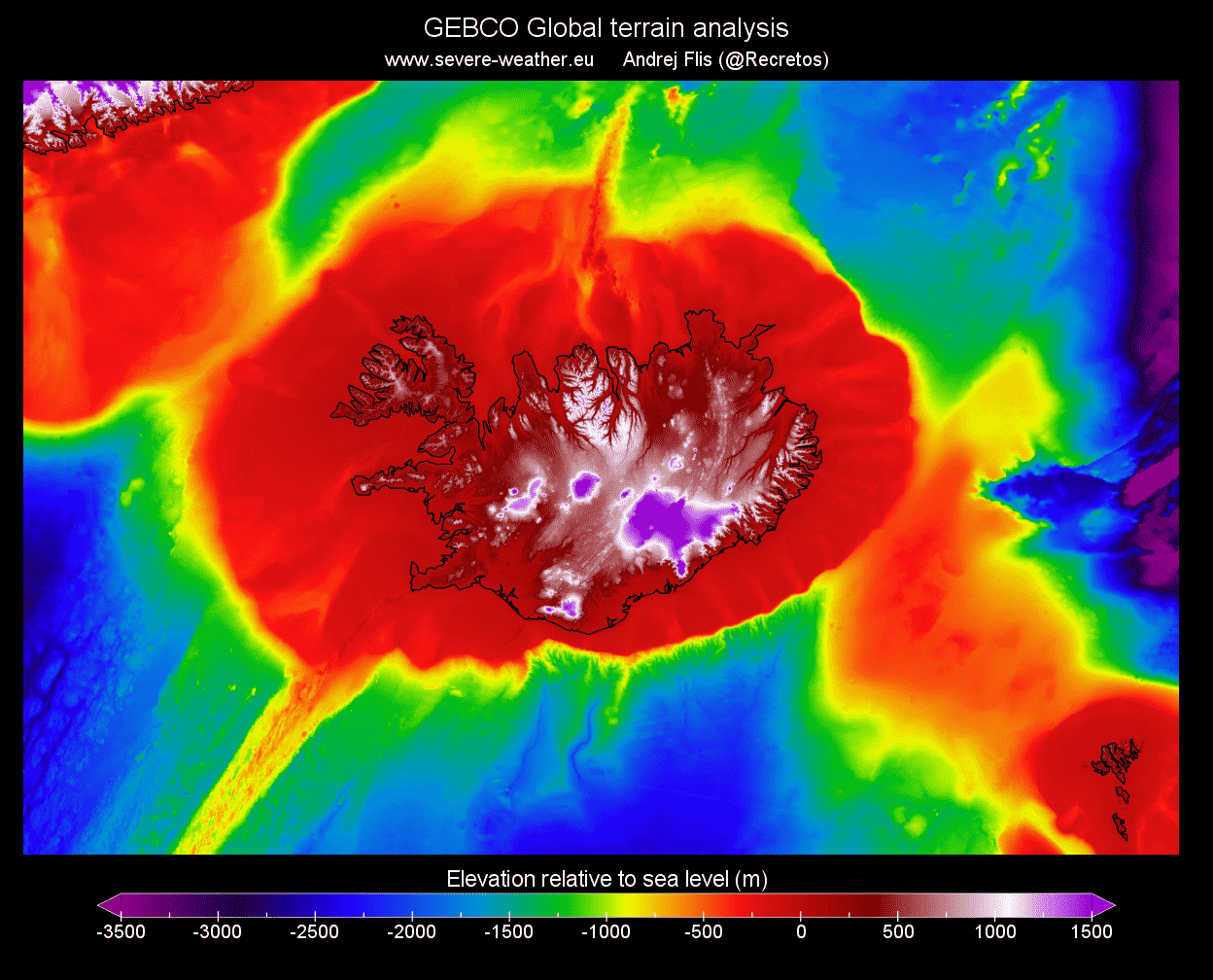

In the image below we can see the Earth’s terrain without the oceans. You can nicely see the Mid-Atlantic ridge coming from the southwest. And also you can see the large “lava flow” of sorts, on which Iceland sits. It was produced as the mantle plume pushed through the spreading plates.

The plume has its pulses or cycles, causing periods of higher and lower volcanic activity in Iceland. We have entered a new period of increased activity in recent years/decades. This plume lies under the whole of Iceland, but its very center lies under the largest Icelandic glacier called Vatnajokull.

Below is an image that shows the approximate center of where the plume connects with Iceland under the Vatnajokull glacier (black circle).

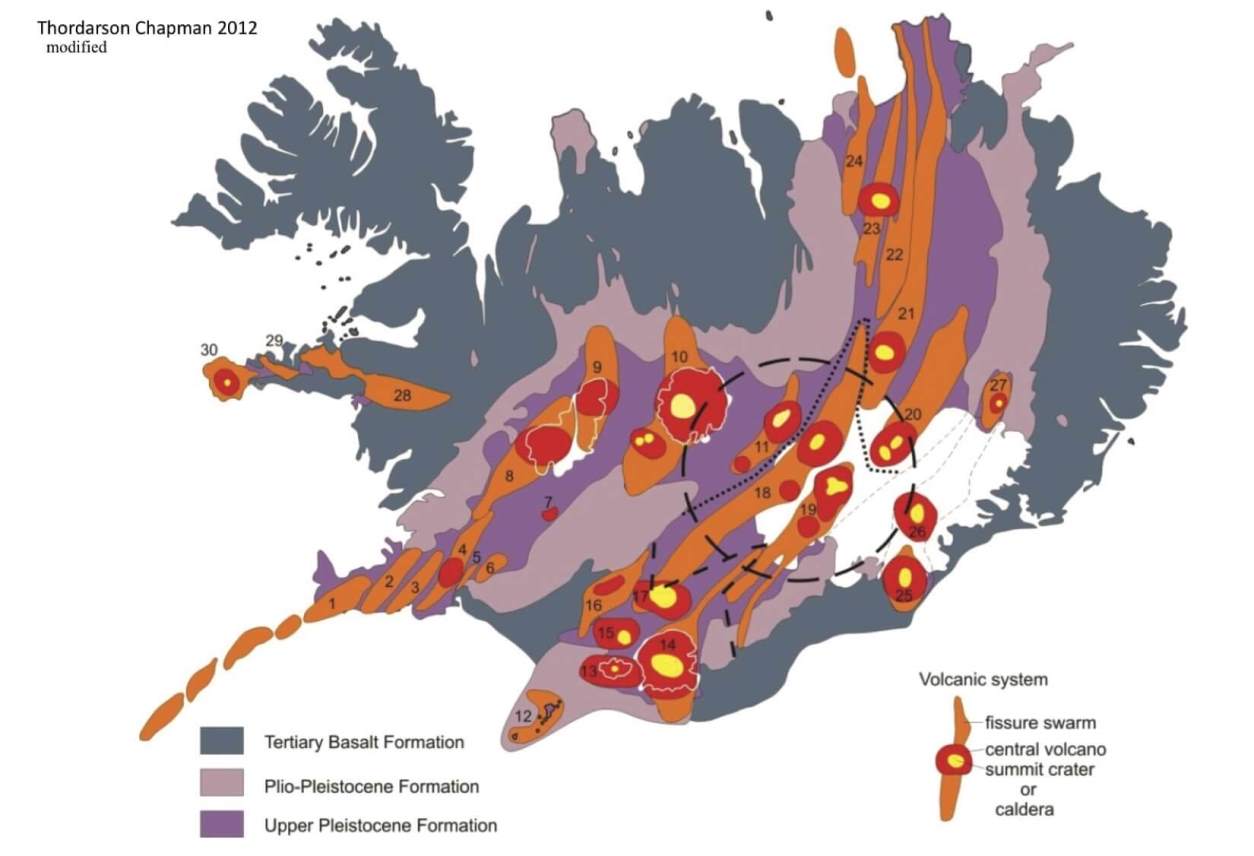

Vatnajokull is the largest glacier in Iceland and the largest ice cap in Europe. It covers roughly around 7.900 km2. Under this glacier, many different volcanoes are hidden, covered by hundreds of meters of solid ice and snow. The image below shows the main central volcanoes beneath Vatnajokull. The most important two volcanoes are Bardarbunga and Grimsvotn.

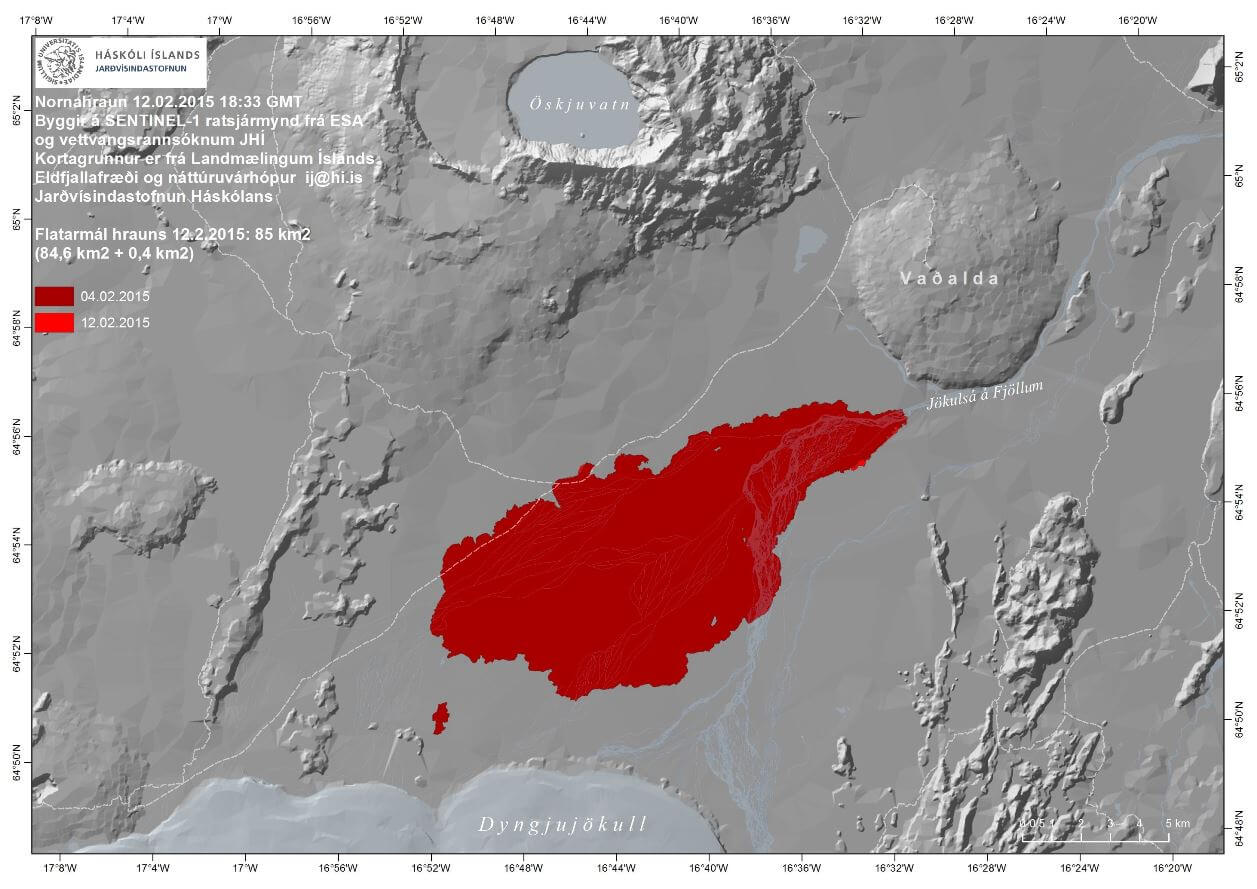

The Bardarbunga volcano last erupted in 2014. But the eruption occurred outside of the glacier, as magma traveled below the ground for over 40km towards the northeast, before erupting.

The eruption was of the more peaceful “Hawaiian style“, and lasted for 6 months (August 2014 to February 2015). Below is an image of the lava field outside Vatnajokull at the end of the eruption, covering 85 square kilometers (33 square miles).

The other major volcano under the glacier is Grimsvotn. It last erupted in 2011, and unlike the peaceful lava flow of Bardarbunga in 2014, it was very explosive. Grimsvotn is one of the major candidates for the next explosive eruption in Iceland, so we will take a closer look at it. Below is an image of the explosive eruption start in Grimsvotn on May 21, 2011.

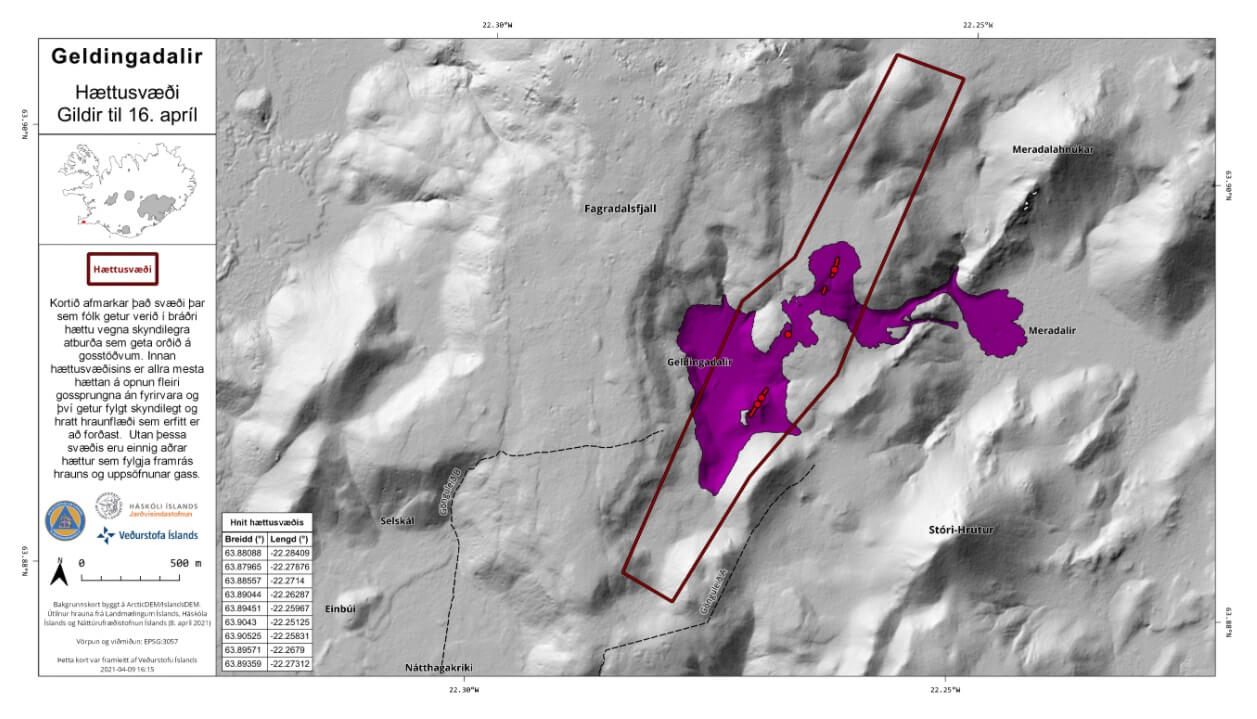

VOLCANO ERUPTION 2021

There is a volcanic eruption in Iceland every 4-6 years on average. The last eruption is actually still ongoing at the time of writing this article and began on March 19, 2021. As in 2014, this is also a more peaceful lava flow eruption, occurring in the Fagradalsfjall volcanic area. This area is found on the Reykjanes Ridge in southwest Iceland, seen in the image below.

Below we have an image of the lava field that erupted so far. The eruptive cones are glowing red, while the erupted lava is already cooling and turning dark in the process. Judging from the webcam live imagery, there is near-constant lava spattering from the vents, which have been building cones above the eruption points. Photo by: Almannavarnir/Björn Oddsson.

The Icelandic Met Office (IMO) estimates that around 7,5 million cubic meters (265 million cubic feet) of lava has erupted so far from all vents. Below is a map from IMO, that shows the 4 eruption points (red lines/dots) and the current spread of the lava flows.

EXPLOSIVE GRIMSVOTN VOLCANO

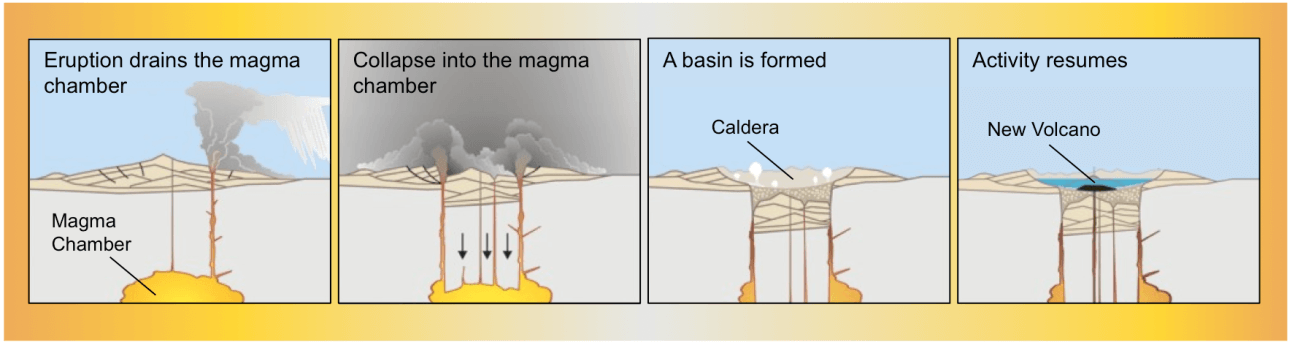

Grimsvotn is a subglacial volcano, covered by snow and ice. It is not a typical pointy-mountain volcano, but a caldera complex, made out of individual calderas. Its calderas were formed over the hundreds of years, after large eruptions.

A caldera is a depression in the ground, formed as the ground sinks after an eruption. The ground sinks down into the void under the volcano, which was previously occupied by the magma that has now erupted. Some of the strongest volcanoes in the world are actually large calderas.

Grimsvotn erupts quite regularly, with its last 3 eruptions being in 1998, 2004, and 2011. This gives an average of about 6-7 years between eruptions. Its last eruption began on May 21 and ended on May 28, 2011.

It is now almost 10 years since this event. But this was a big explosive eruption, so the volcanic system can take more time to recover and recharge. Below is a satellite image from NASA/MODIS, of the ash cloud during the 2011 eruption.

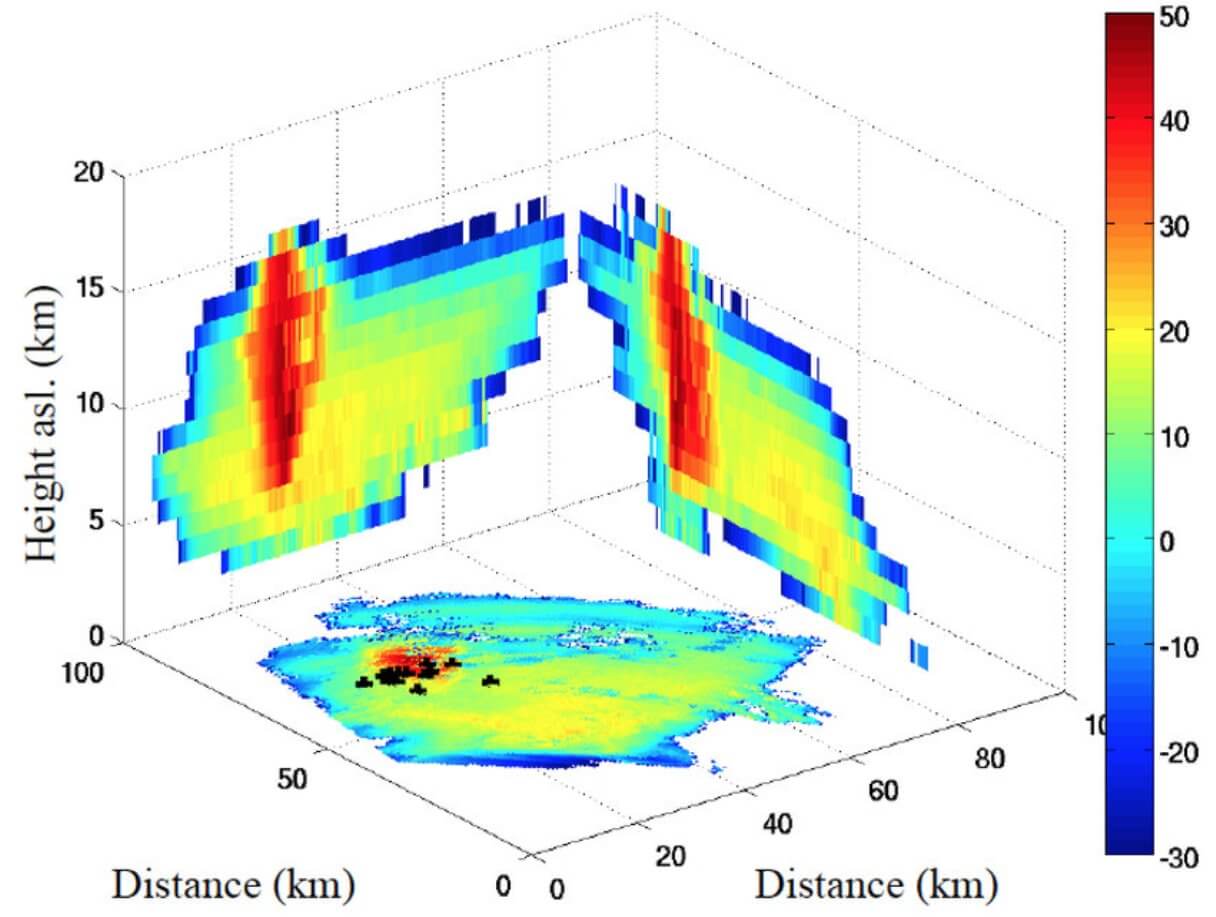

The last eruption of Grimsvotn was the largest explosive event in over 100 years in Iceland. The ash plume rose up to 20km (12 miles) high, creating a large ash cloud. The image below is a radar scan of the ash column, with its tops rising over 15km in altitude at the time of the scan.

The ash cloud caused some air travel disruption, canceling around 900 flights across Europe. That is a relatively low number, compared to 95.000 flights that were canceled just a year before.

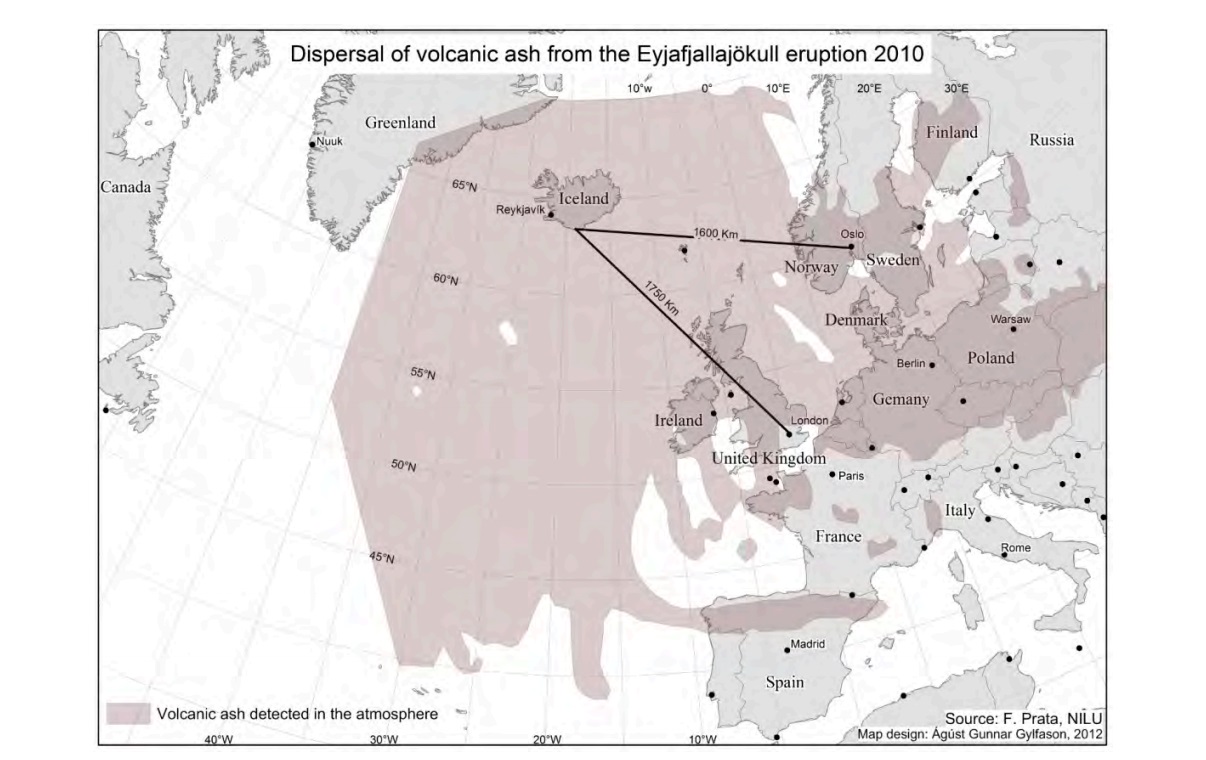

In the spring of 2010, the Eyjafjallajokull volcano erupted, sending an ash cloud directly towards Europe. It caused widespread air traffic cancelation, damaging the global economy for billions of dollars. The image below shows the ash dispersal over Europe in 2010.

Grimsvotn’s 2011 eruption was much bigger than the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajokull, yet it caused only 1% of the total flight cancellations that we have seen during the 2010 eruption. The image below shows the rising ash column during the 2011 eruption, taken by Ólafur Sigurjónsson.

There were much fewer air flights canceled in 2011 because the high altitude winds carried the ash cloud mostly away from Europe. And also because new air traffic rules and protocols were introduced following the 2010 eruption. Flights are now canceled only when a certain concentration or amount of ash is reached or detected at the airplane flight level.

But despite the new rules, if the winds would carry the 2011 ash cloud towards Europe, it would still cause heavy air traffic disruption.

But why are some eruptions in Iceland very calm lava flows, and some can send ash clouds around the Northern Hemisphere? The answer is ice. Eruptions in Iceland can get very explosive from volcanoes that erupt under ice (a sub-glacial eruption). That is because the rising hot magma meets ice (or water/lake under the glacier) on its way to the surface, causing an explosive reaction.

READY TO ERUPT

Many say that the Grimsvotn volcano is overdue for an eruption. But volcanoes are never overdue, as they can change their behavior at any time. The Grimsvotn volcano can sleep for more than 15 years without an eruption, but that is a relatively rare occurrence in modern records.

Below: Grimsvotn ash cloud in 2011. Photo by Egill Adalsteinsson.

Current data indicates that Grimsvotn has entered its last phase before the eruption. It is currently one of the top 3 candidates for the next big Icelandic eruption, along with Hekla and Katla volcanoes in the south. Hekla is a safe bet for an eruption at any time, without much prior notice and with less than a few hours of intense earthquake activity before erupting.

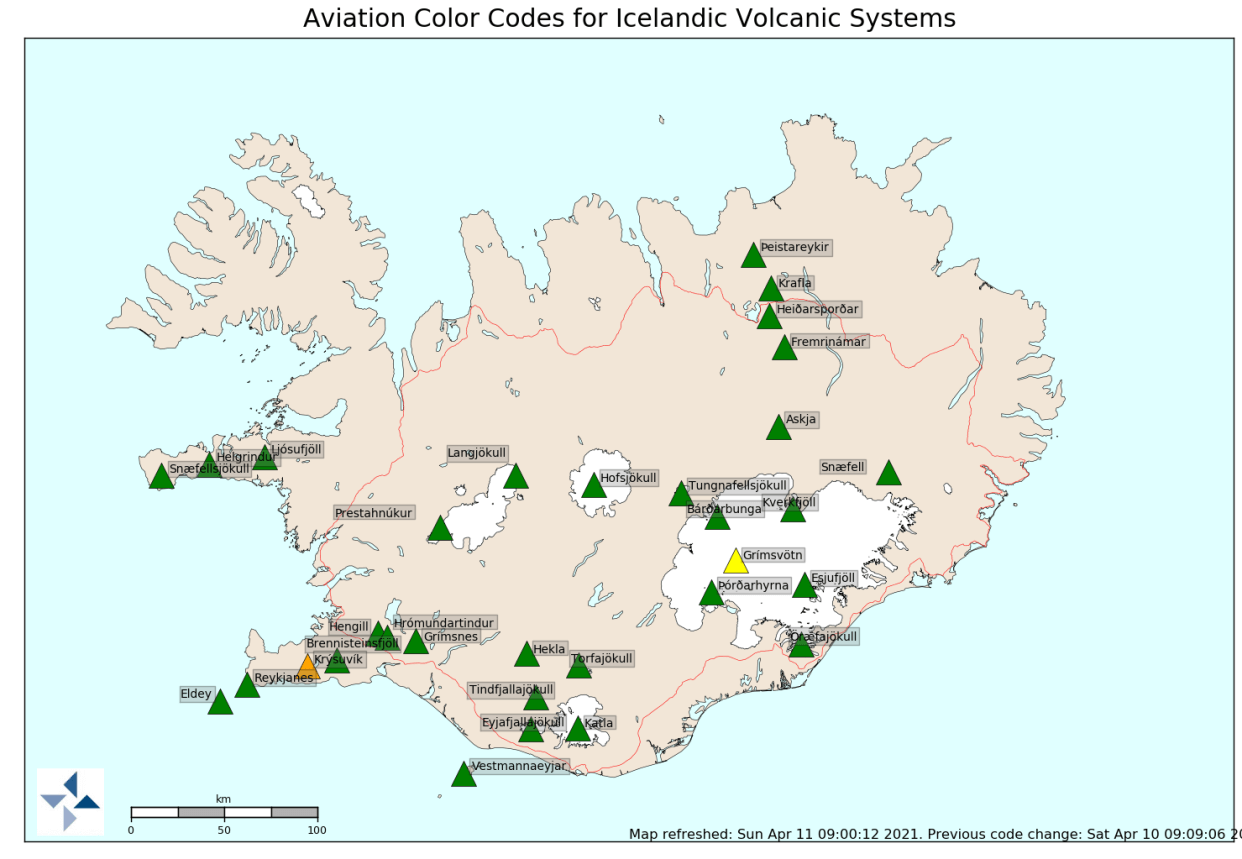

At Katla on the other hand, we will see a few days to weeks of intense earthquake activity as it finally builds up to an eruption. On the graphic below we can see the location and current status of all the main volcanoes in Iceland, monitored by the Icelandic Met Office (IMO). The green color means that the volcano is in its normal, non-eruptive state.

Grimsvotn is the only volcano of the 3, that is already at the yellow alert level. It has regular earthquake activity, and the GPS data confirmed that it is getting close to an eruption.

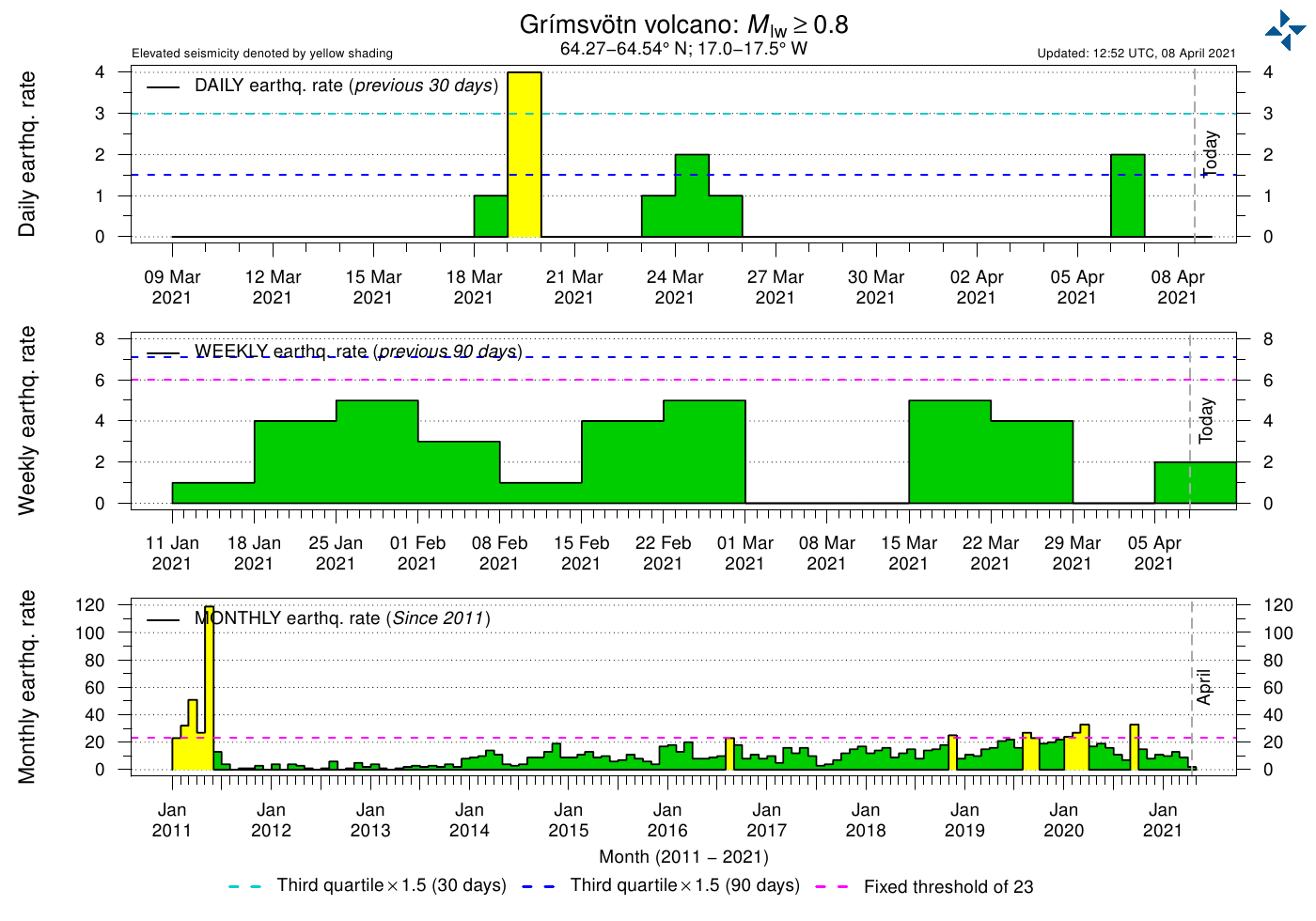

We are tracking a slow but very steady increase in the number of earthquakes at Grimsvotn. In March 2020, we saw the highest monthly earthquake rate since the eruption in 2011.

A steady and persistent increase in earthquake activity is usually one of the main signs that a volcano is slowly getting close to an eruption. The graphic below by IMO, shows the daily, weekly, and monthly earthquake rate over time.

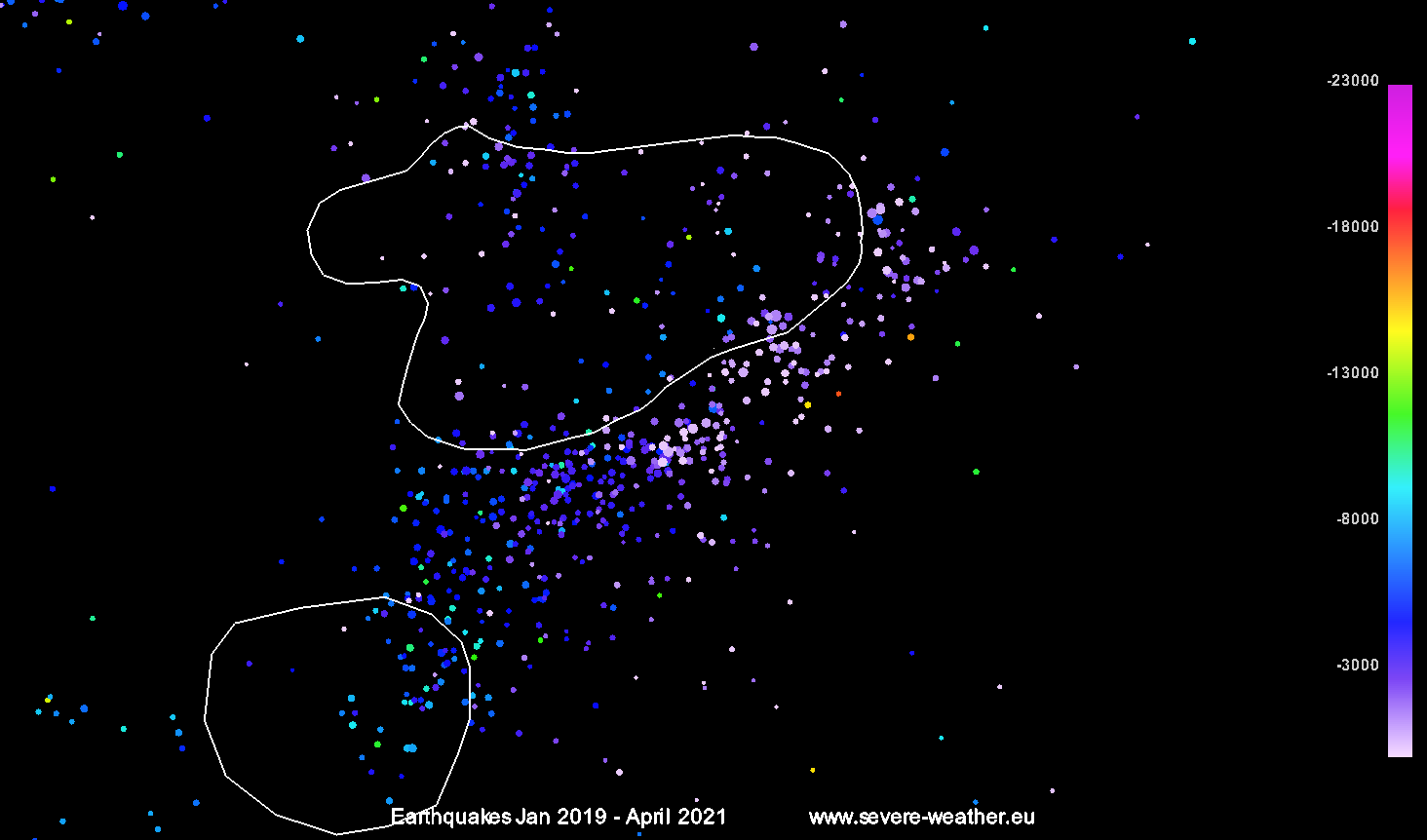

We produced a map of earthquakes at Grimsvotn from 2019 to 2021. The north outline is the rough area of the Grimsvotn calderas. The south outline is another volcano, which is a part of the Grimsvotn volcanic system. Colors show the depth of the earthquakes in meters.

You can see that most of the earthquakes are on the south and east side of Grimsvotn. They mostly occur as the magma chamber below the volcano is recovering, and rebuilding pressure. That causes strain on the crust around it, cracking the ground, which is what we detect as earthquakes.

But, earthquake numbers only tell us only one part of the story. Sometimes it is more important to look at the earthquake power and energy release. Two or three strong earthquakes can have a bigger impact than 100 smaller ones.

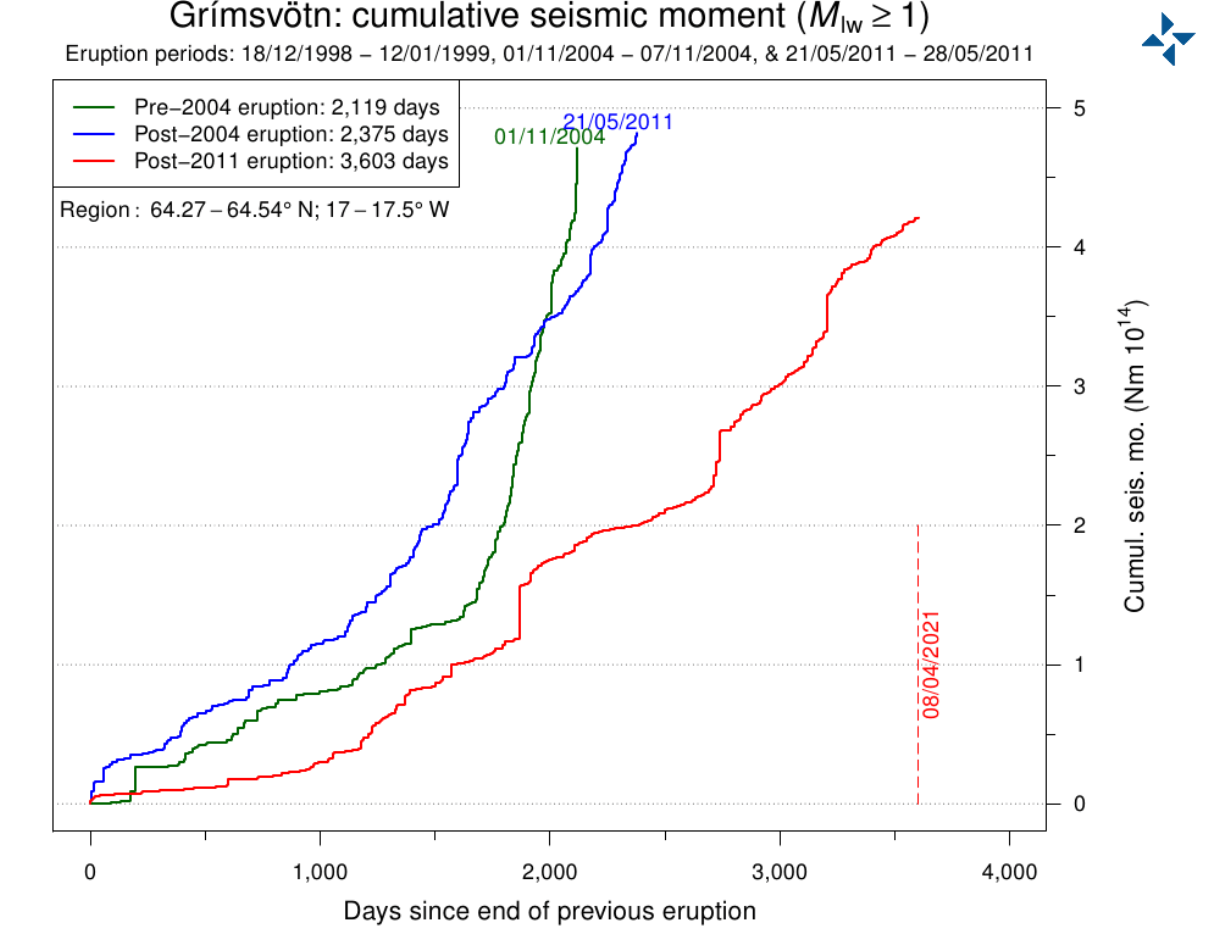

The image below by IMO shows the earthquake energy release at Grimsvotn, and it is fairly simple to read. We see that a certain amount of energy release is needed for Grimsvotn to start an eruption, like in 2004 and 2011.

That is directly related to the pressure increase in the volcano, and we are slowly getting close to the eruptive values. The trend has increased lately, and with stronger earthquakes and more pressure in the volcano, it is likely for Grimsvotn to erupt within the next 6-12 months.

But to be more certain, we also need to look at ground movement around the volcano. We need to find signs that earthquakes are being caused by the fresh hot magma that is entering the volcanic system underground, accumulating there and increasing the pressure in the volcano. Just like inflating a balloon until it explodes. The process of accumulating magma and ground deformation is called inflation.

Grimsvotn is one of the most steadily inflating volcanoes in Iceland, as seen on the monitoring equipment. As it lies very close to the center of the Icelandic plume, it has a constant feed of fresh material into its magmatic system.

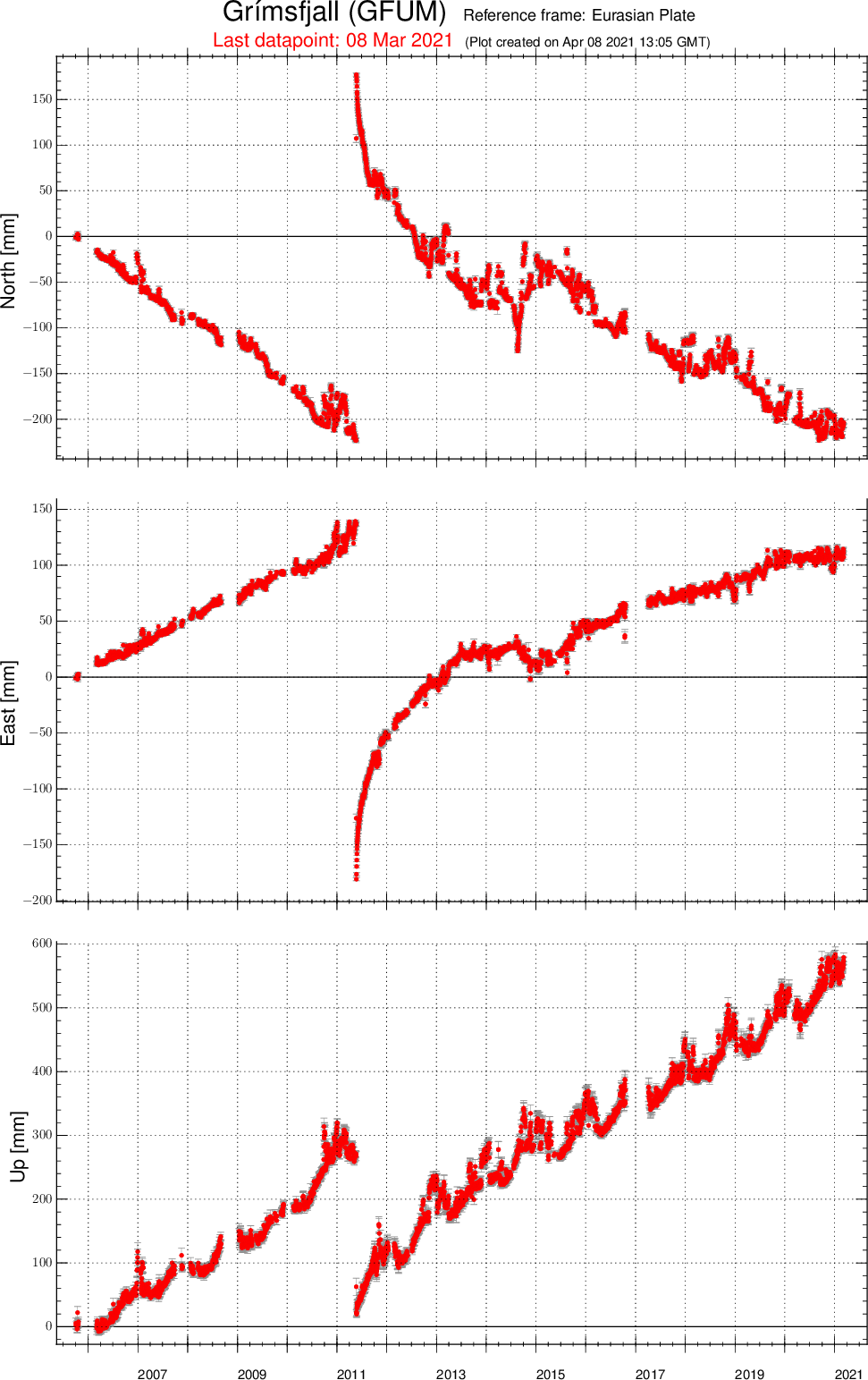

The plot below from IMO shows the data from a GPS station at Grimsvotn, which is monitoring the ground movement. What is most important here is the very bottom graph, which shows the ground moving up or down.

We can see that since the last eruption in 2011, the ground at Grimsvotn has raised by almost 60cm (2ft). That is due to the magma accumulating under the volcano and causing enough pressure to push the ground up. It is a normal occurrence at most volcanoes that are getting ready to erupt. But there is no rule that would tell us how much a volcano has to inflate before it erupts.

Grimsvotn is a very likely candidate to have a large explosive eruption in the near future. It is powerful enough to have an effect on Europe and further around the Northern Hemisphere.

Another large explosive eruption (like in 2011) could severely limit air traffic again if the wind would take it towards Europe. That could have a global economic impact, which is why large explosive volcanoes in Iceland are closely monitored. Of course, we also have to consider the direct impact of ash on daily life in Iceland.

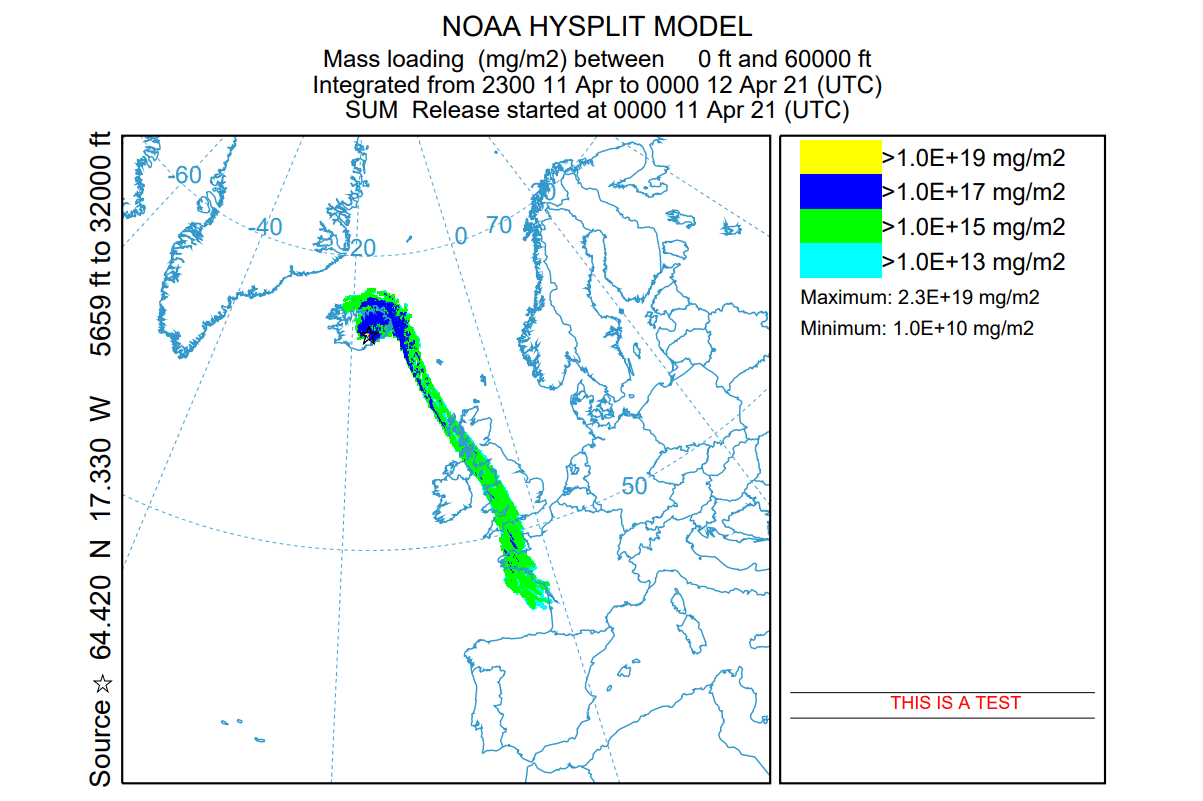

We produced an image, which shows the movement of the ash cloud if Grimsvotn would have a medium-sized eruption today. This is just a simulation, but the ash cloud would reach over the UK and into France in under 24 hours. The concentrations would likely be high enough to partially close the airspace in western Europe.

VOLCANIC HISTORY

In 1783, an eruption occurred in Iceland, on the Laki fissure line, which is actually part of the Grimsvotn volcanic system. The eruption of the Laki volcanic fissure in the south of the island is considered by some experts to be the most devastating in Iceland’s history. It caused the biggest Icelandic environmental, social, and economic catastrophe. 50 to 80 percent of Iceland’s livestock was killed, leading to a famine that left a quarter of Iceland’s population dead.

The volume of lava that erupted was large. Nearly 15 cubic kilometers (3.6 cubic miles) of lava erupted, which is the second-biggest recorded on Earth in the past millennium. Below is a map, showing the location of the Laki fissure line inside the two red lines.

The impact of the Laki eruption was huge and extended well beyond Iceland. Global temperatures dropped, with crop failures and famine in Europe as millions of tonnes of sulfur dioxide and hydrofluoric acid clouds were released into the Northern Hemisphere. Some experts have suggested that the consequences of the eruption may have played a part in triggering the French revolution, but this is still a matter of discussion.

Laki is a part of the large Grimsvotn volcanic system, which extends well beyond the main Grimsvotn caldera complex, and includes several other volcanoes. Another Laki style and size eruption in our lifetime is unlikely. The main global effects in the near future are large ash clouds, that can disrupt the air traffic, impacting the already fragile world economy. In a strong explosive eruption event, ash deposits are also likely in Europe.

We will keep a close eye on Grimsvotn and all the volcanoes in Iceland, informing you of any significant development. The official agency in Iceland for monitoring volcanoes is the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO), where you can find live data, additional information, and all official warnings.

DONT MISS: