With supercells being reported left and right, what are the most typical and telltale signs that a storm may be a supercell?

Not every severe thunderstorm is a supercell, and not every supercell is a severe thunderstorm. Many thunderstorms with impressive visual structures are reported as supercells but may be of another type – such as multicells and squall lines.

A significant fraction of supercell thunderstorms are severe, producing large to giant hail, extreme torrential rainfall, severe straight-line winds, and tornadoes. Supercells form strongly sheared environments with favorable vertical wind profiles and are the least common type of thunderstorms. Locally, favorable regional terrain configurations and mesoscale meteorological factors may favor supercell formation.

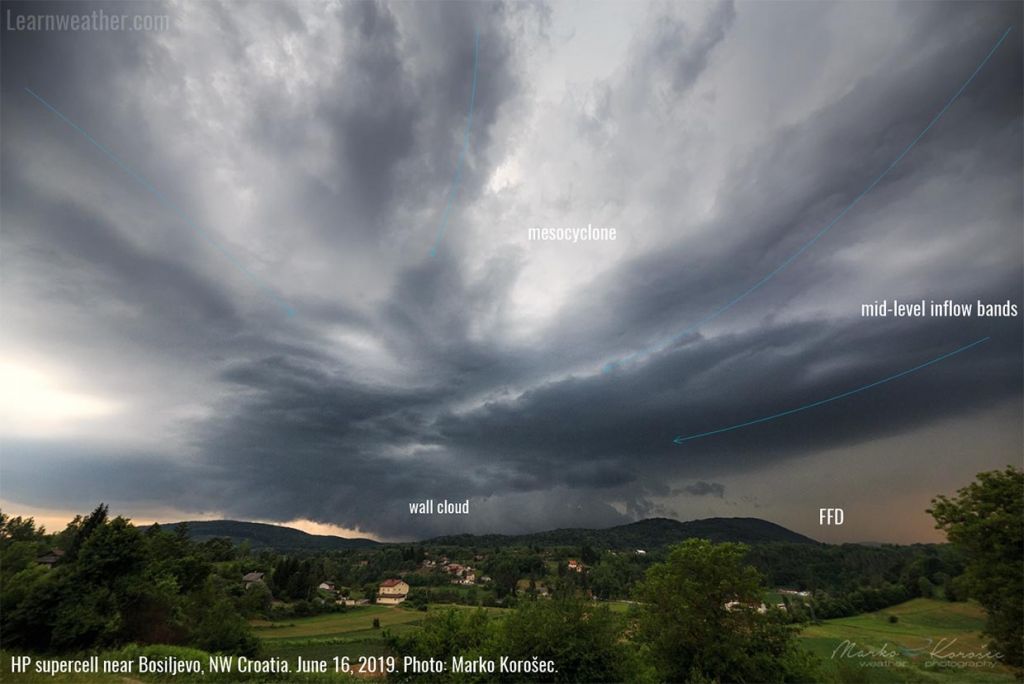

Supercells are highly organized thunderstorms. They share a common set of dynamic features, three key elements: a persistent rotating updraft or mesocyclone and two distinct downdrafts, the forward flank downdraft, and the rear flank downdraft.

This leads to the development of distinct visual features in supercells. While there is much variation in shape, size, and appearance, supercells share several distinctive features. Knowing these may help you spot a supercell in the field. Here are 10 visual signs a storm may be a supercell.

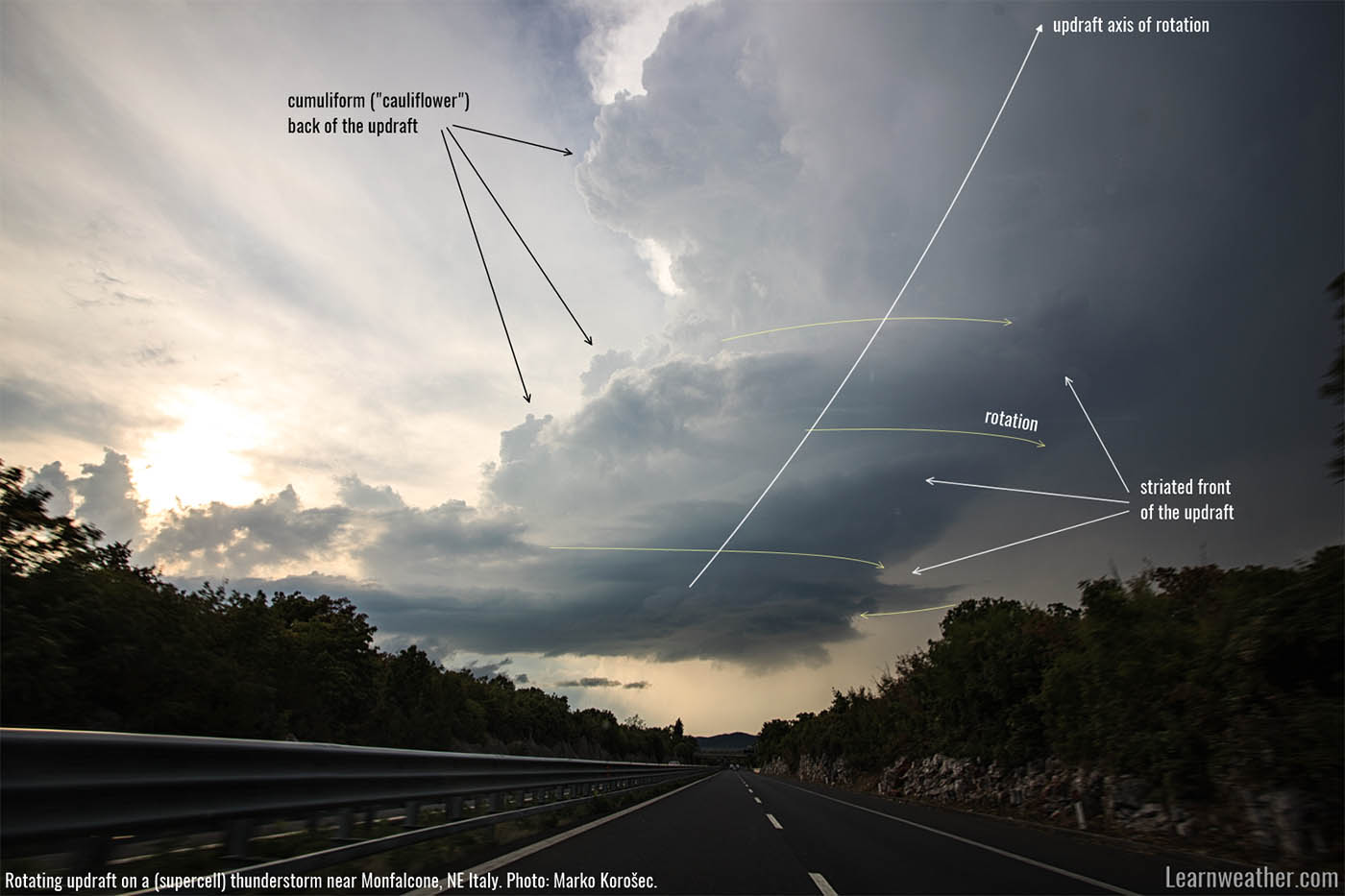

1. Tilted updraft

Supercells form in strongly sheared environments. As the wind increases with altitude, it tilts the supercell’s updraft producing a typical slanted appearance.

2. Two distinct downdrafts/precipitation areas

Supercells develop two dynamically distinct downdrafts. The Forward Flank Downdraft, or FFD, is a region of descending air located on the forward part of a supercell thunderstorm. It is composed of cold and moist air, dragged down by entrainment of precipitation (or water loading) and negative buoyancy due to evaporation cooling. The FFD produces both rain and hail.

The Rear Flank Downdraft, or RFD, is a region of descending air located on the rear trailing part of a supercell thunderstorm. The RFD can form due to evaporation cooling and consequent negative buoyancy (i.e., thermodynamically) or the storm’s updraft blocking the mid-level airflow (i.e., dynamically). In dynamic origin, the RFD forms as the rotating updraft obstructs mid-level flow on the upwind side of the storm.

Air on the backside of the supercell begins to sink, forming the RFD. The RFD is cooler than the inflow at the surface but typically warmer than the FFD. The RFD is forced downwards from mid-levels, undergoing compressional (adiabatic) heating. Conversely, the FFD descends due to precipitation loading (entrainment) and evaporation cooling.

In other words, the RFD is pushed down and warms on its way down. In contrast, the FFD is dragged down by precipitation and additional negative buoyancy due to evaporation cooling. Varying amounts of rainfall can be entrained from the FFD into the RFD by the rotation of the mesocyclone.

3. Wall cloud

The wall cloud (murus or pedestal cloud) is a pronounced lowering in a supercell’s rain-free base. It forms as rain-cooled air from both the RFD and FFD is pulled upward (entrained) with the warmer inflow air into the updraft.

As the rain-cooled air is cooler and humid, the mixed, rising air condenses quicker and, therefore, lower (at lower altitudes) than the air in pure inflow. Wall clouds can be rotating or non-rotating, depending on the low-level winds and dynamics of the thunderstorm. Forming wall clouds can present different appearances.

4. Inflow tail

The inflow tail (sometimes called a tail cloud) is a tail-like extension of the wall cloud in the direction of the inflow. It forms as the warm, moist inflow air comes into contact with the cooler air in the forward flank downdraft (FFD) being entrained into the inflow.

Inflow tails come in many shapes and sizes, from short stubby extensions of the wall cloud to a long cloud band several kilometers long.

5. Convergent mid-level inflow bands

Supercells often display mid-level convergent inflow bands. There may be one dominant inflow band or multiple smaller ones. They are known in storm chaser jargon and also as feeder bands.

6. Striated mesocyclone

Supercells, particularly isolated ones, often develop distinct striations in the lower part of the mesocyclone. Striations appear as more or less distinct linear features, which can take on the appearance of stacked plates in the most extreme cases. Indeed, stacked plates are jargon storm chasers used to describe a strongly striated mesocyclone.

Note, however, that squall lines can also produce multi-layered shelf clouds with a striated appearance.

7. Clear slot / RFD slot

The RFD cut, or clear slot in storm chaser jargon, is a distinctive feature of a well-developed supercell. The RFD cut can be rain-free and visually clear, partly obscured by rain, or entirely obscured by heavy rain. The RFD cut forms as the RFD descends and wraps around the trailing part of the updraft.

As the air in the RFD descends, it cuts a clear notch into the storm’s rain-free base. This is a visually very distinct feature. It sculpts the rain-free base into a recognizable U-shape or horseshoe shape.

8. Vault region

The vault is a visually apparent region between the tilted updraft and the forward flank (FFD). The vault is not developed on all supercells and depends on the tilt of the updraft and offset of FFD precipitation.

9. Very large hail

Very large hail, over 5 cm in diameter, is most typically produced by supercells.

10. Rotational features

Supercells often develop a visual appearance that is indicative of rotation. This may be due to stacked plates mesocyclone, mid-level inflow banding, updraft appearance, or other visual features – supercells frequently indicate rotation by their look.

It often pays off to discern supercell characteristics in the field. Even relatively small and seemingly non-severe supercells can quickly produce large or very large hail (5+ cm). You may be able to avoid driving into a severe hailstorm or torrential rainfall. Or, it may help you appreciate the nature of the storm from a safe distance.

Related topics: