The Arctic sea ice extent is approaching the annual minimum with a situation definitely not bad as in recent years. At the end of August 2022, almost five and a half million square kilometers of sea ice are still present in the Arctic ocean. It is now time to see which is the forecast for the September sea ice extent. How much ice will be spared at the end of the ablation season will have a crucial influence on the late Fall and Winter weather both for USA and Europe, as well as for Asia.

ARCTIC SEA ICE AT THE END OF SUMMER 2022

The Arctic sea ice extent on August 26, 2022, is 5.478 million square kilometers according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The decline rate of the extent through August was near the 1981 to 2010 average. Nevertheless, the Arctic sea ice extent is running close to 2 standard deviations lower than the average, which means that 2022 is indeed a bad year in the general contest.

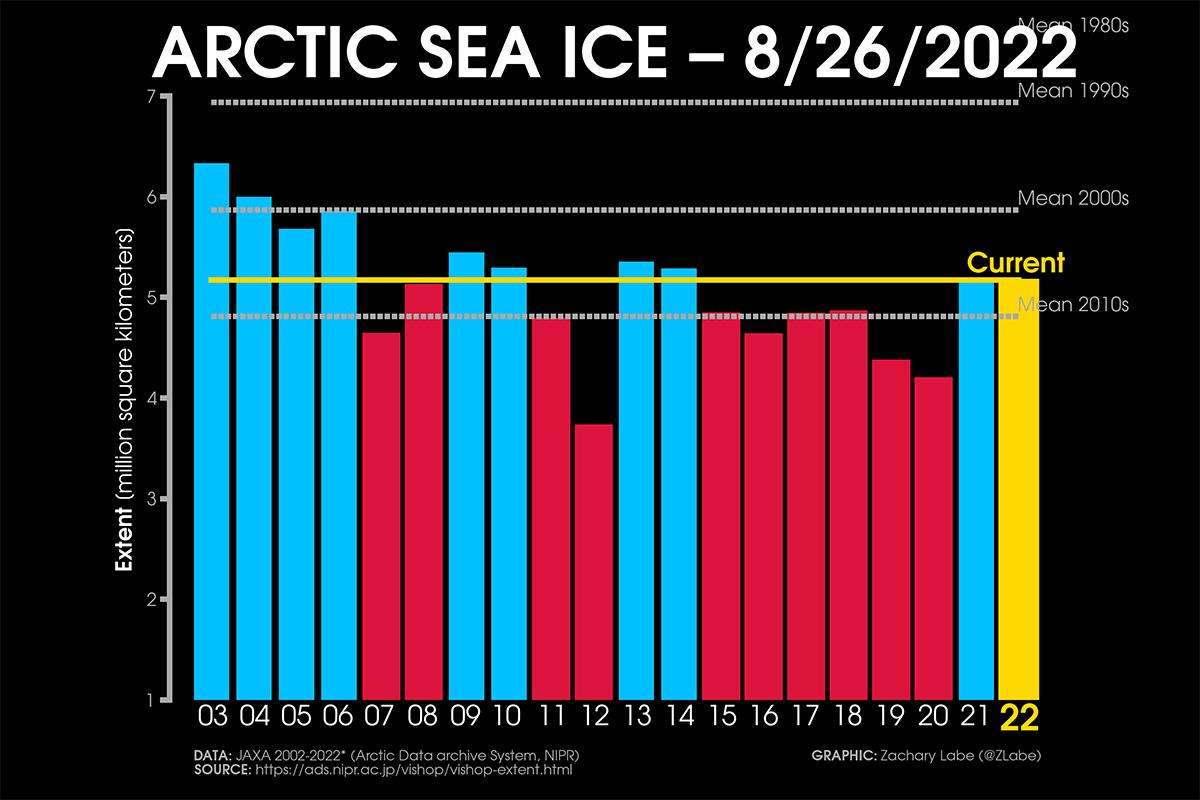

Although this extent is the highest in the last 8 years in the satellite record roughly 0.5 million square kilometers above the 2011-2020 average, according to the Arctic Data archive System NIPR, a lot of ice is missing compared to the long-term climatology.

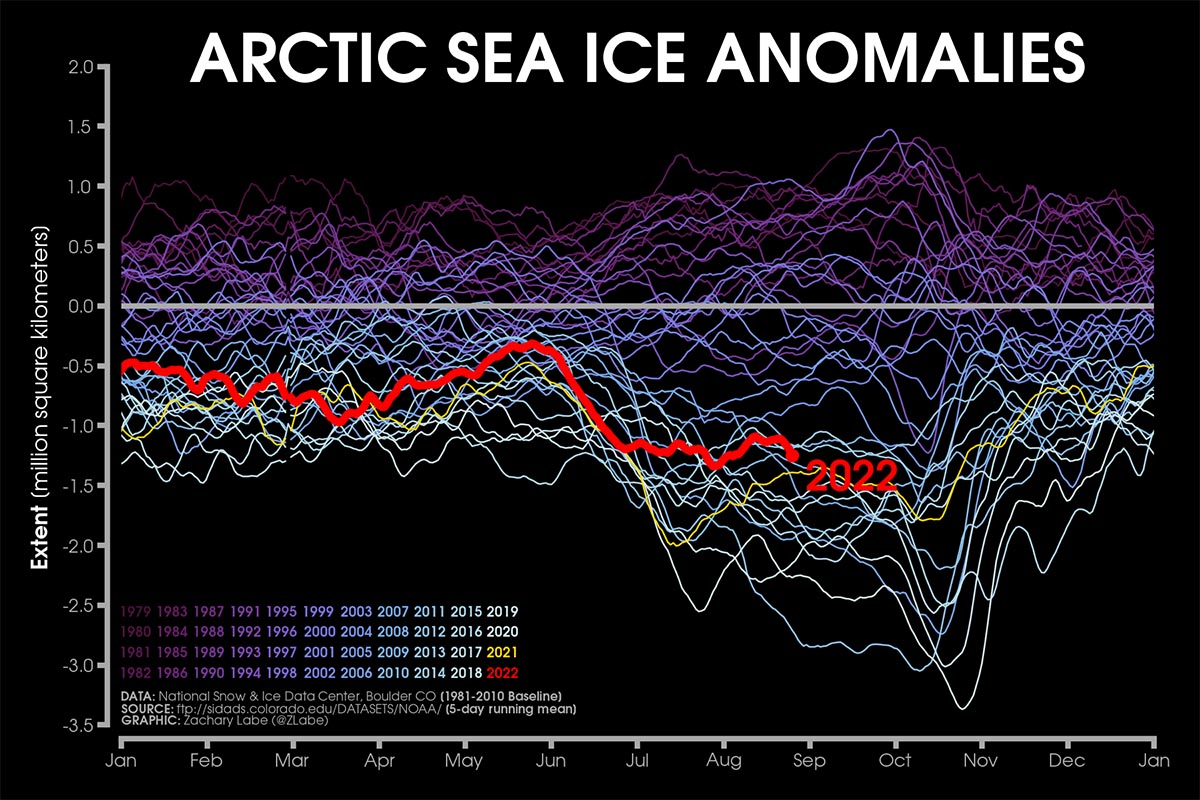

In fact, the sea ice extent is actually about 1.5 million square kilometers below the 1981-2010 average, and 1.9 million square kilometers below the 1979-1990 average. Thanks to a plot made by Zachari Labe we can easily visualize what we just wrote.

The arctic sea ice anomaly, after being rather higher than 2021 through the month of July, increased in August and it is now very close to the 2021 values.

The image below shows the daily Arctic sea ice extent anomalies filtered using a 5-day running mean. 2021 is the yellow curve while 2022 is highlighted with a red line

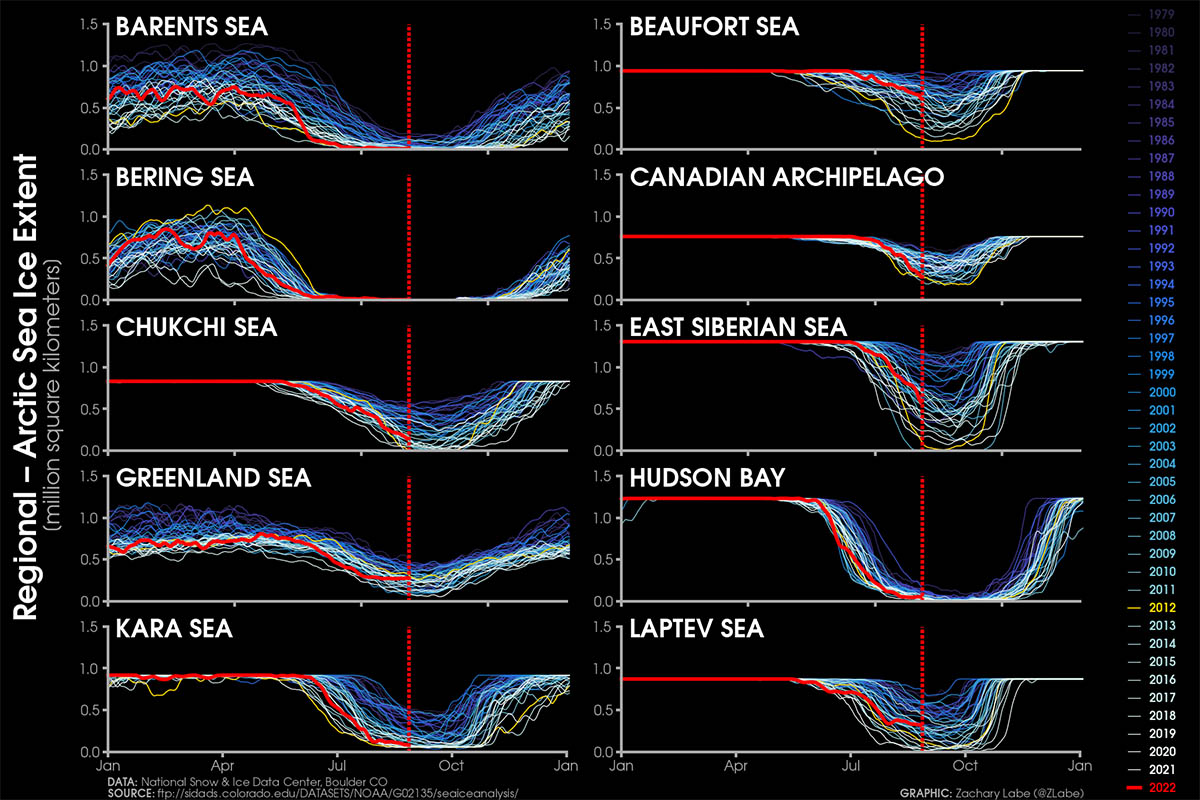

But let’s have a look at the regional behavior. In the image below you can see a map of the regions currently used by the NSIDC to update the regional Arctic sea ice extent bulletin.

Barents Sea, Bering Sea, Kara Sea, and the Hudson Bay are virtually almost free of ice, while the Chucki Sea is rapidly approaching the no-sea-ice threshold. On the other hand, the Beaufort Sea, the East Siberian Sea, and the Greenland Sea still present a decent amount of sea ice this year.

This is particularly evident looking at the image below where the current regional arctic sea ice extents are shown. 2022 is highlighted with a red line and 2012, the worse year ever for the Arctic so far is shown in yellow.

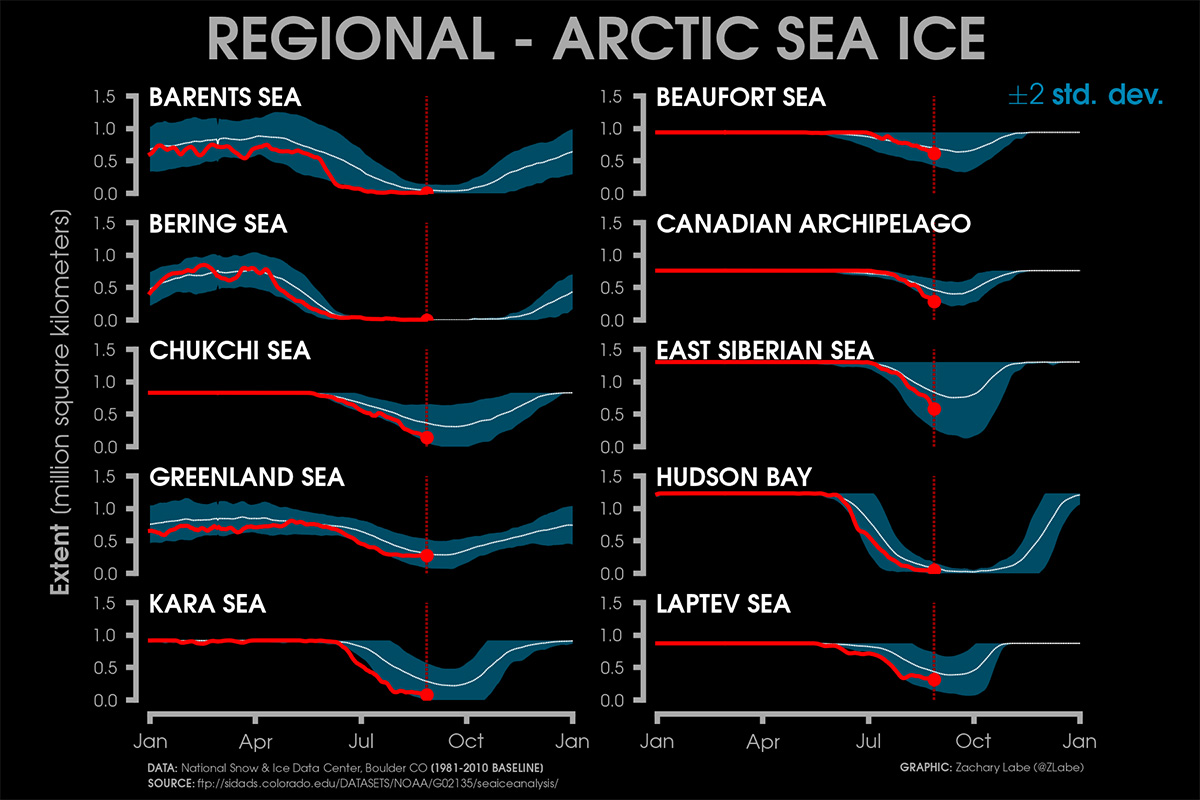

The image below helps to understand better the present situation in the long-term trend. Current sea ice extents in the different regions are presented with 2 standard deviations from 1981-2010 mean.

The rather good situation in the just mentioned sectors is evident. Particularly, the Beaufort Sea and the Laptev Sea show a sea ice extent very close to the 1981-2010 average. Most notably in the East Siberian Sea the ice still extends to the coast, something rather rare in recent years.

WHAT IS SEA ICE

Before delving into the subject, we should know exactly what Sea ice means. Sea ice means all sorts of ice that form when seawater freezes. Sea ice that is not fast ice refers to drift ice, and, if the concentration exceeds 70%, it is called pack ice. When sea ice concentration is lower than 15% this is considered open water, and the boundary between open water and ice is called the ice edge.

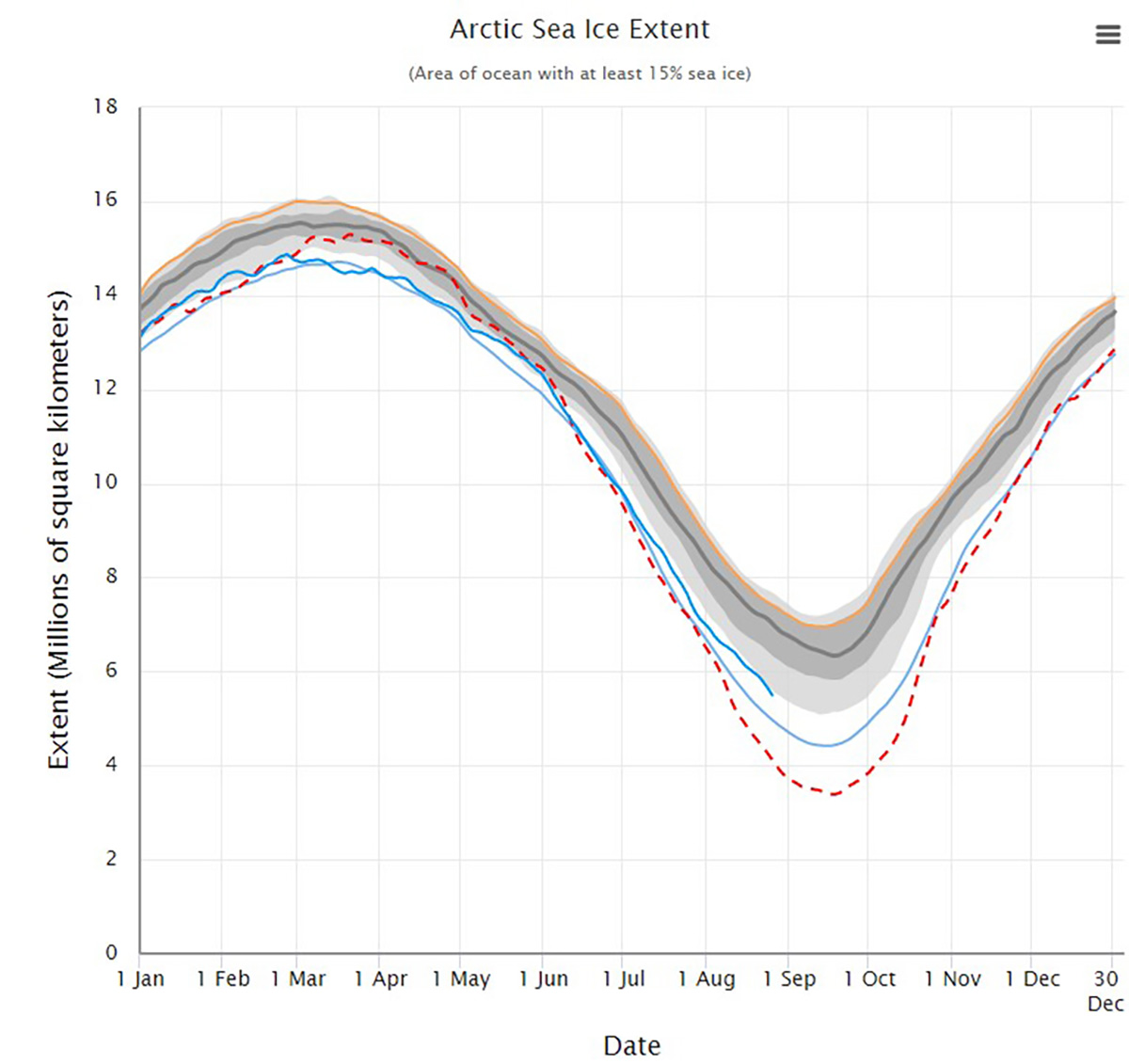

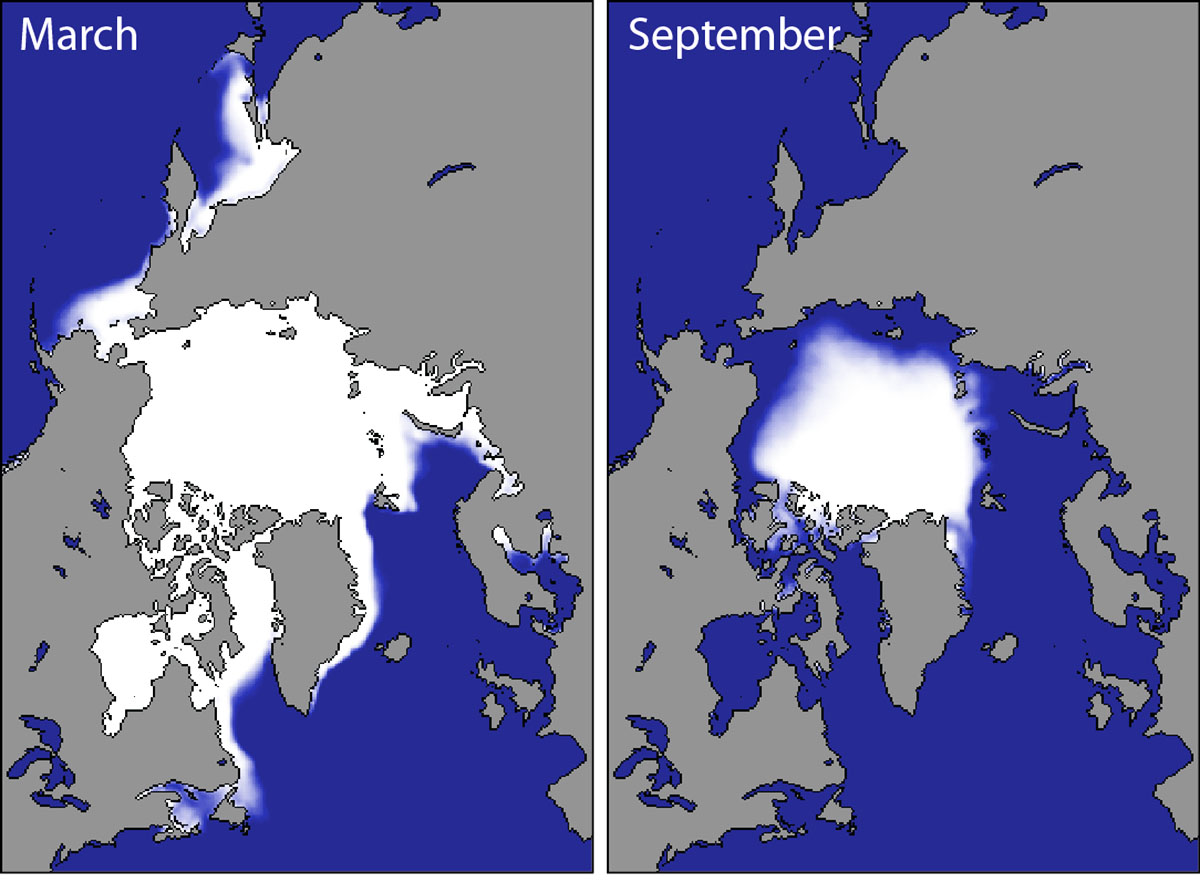

Sea ice cover in the Arctic grows throughout the winter and peaks in March. In September the sea ice extension reaches its minimum, which is generally only around one-third of its winter maximum.

In order to get a proper picture of the sea ice state, there is a need of determining both extents and volumes.

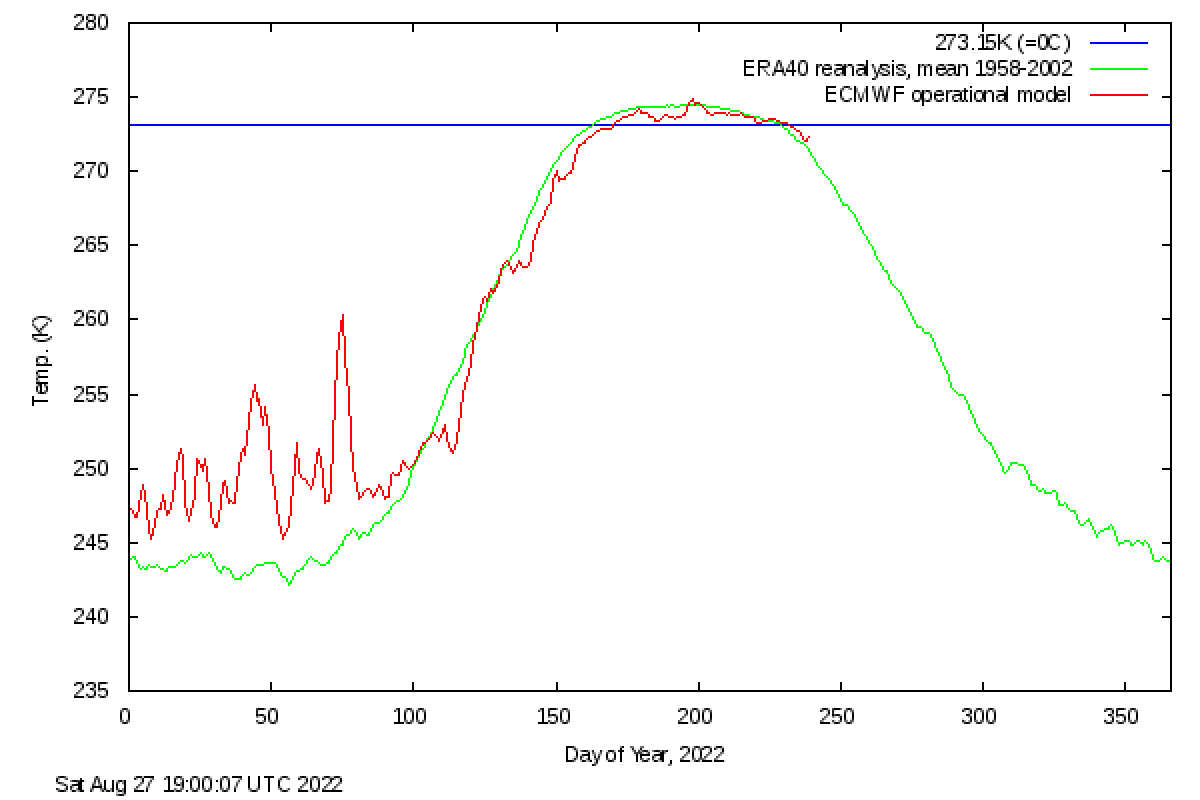

Such numbers primarily include the ice thickness, generally linked to the age of the ice. In the image below, Arctic sea ice climatology from 1981-2010 by the Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder.

Winter ice extent is generally a weaker indicator of what the ice extent will look like in September when we will face the annual minimum. The seasonal cycle of Arctic sea ice is characterized by the maximum annual extent in March, decreasing through spring and summer to an annual minimum extent in September. In the image below the Arctic sea ice extent develops at the end of the winter season (March maximum) and by the end of the summer (September minimum)

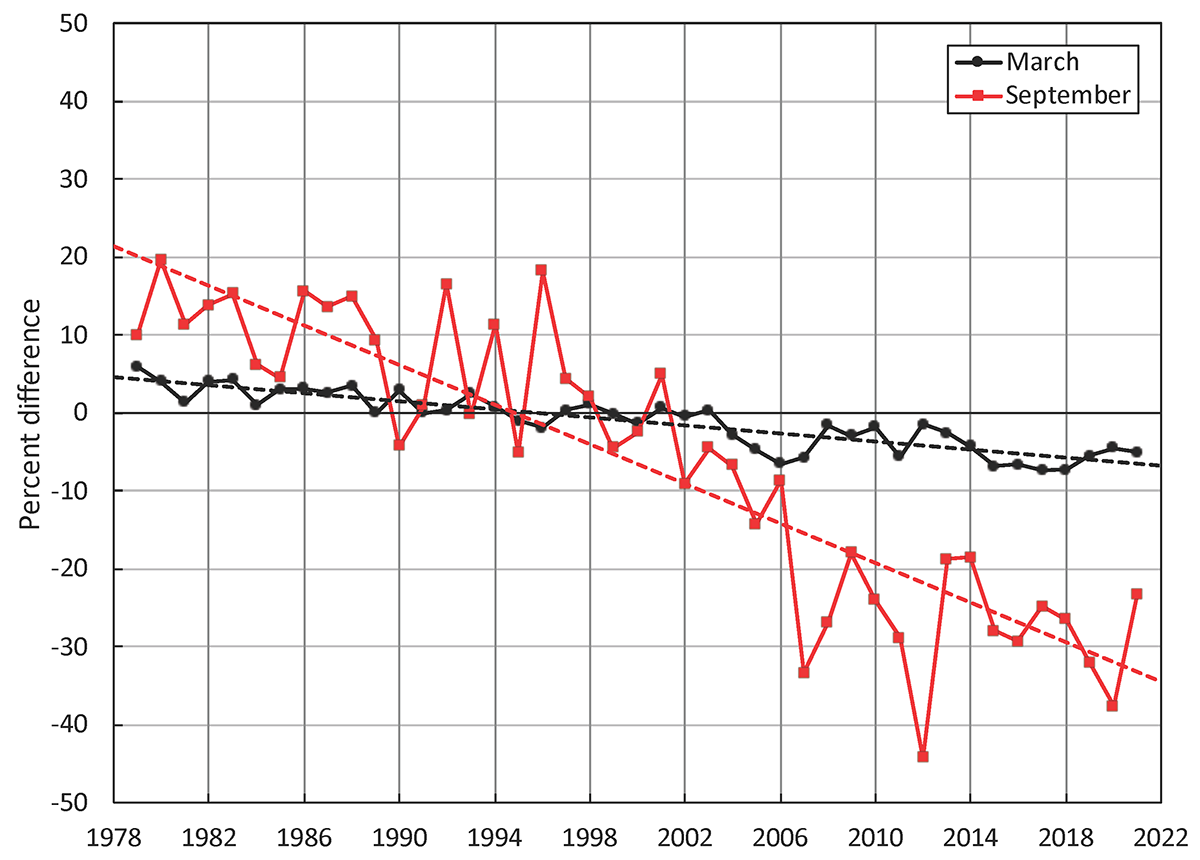

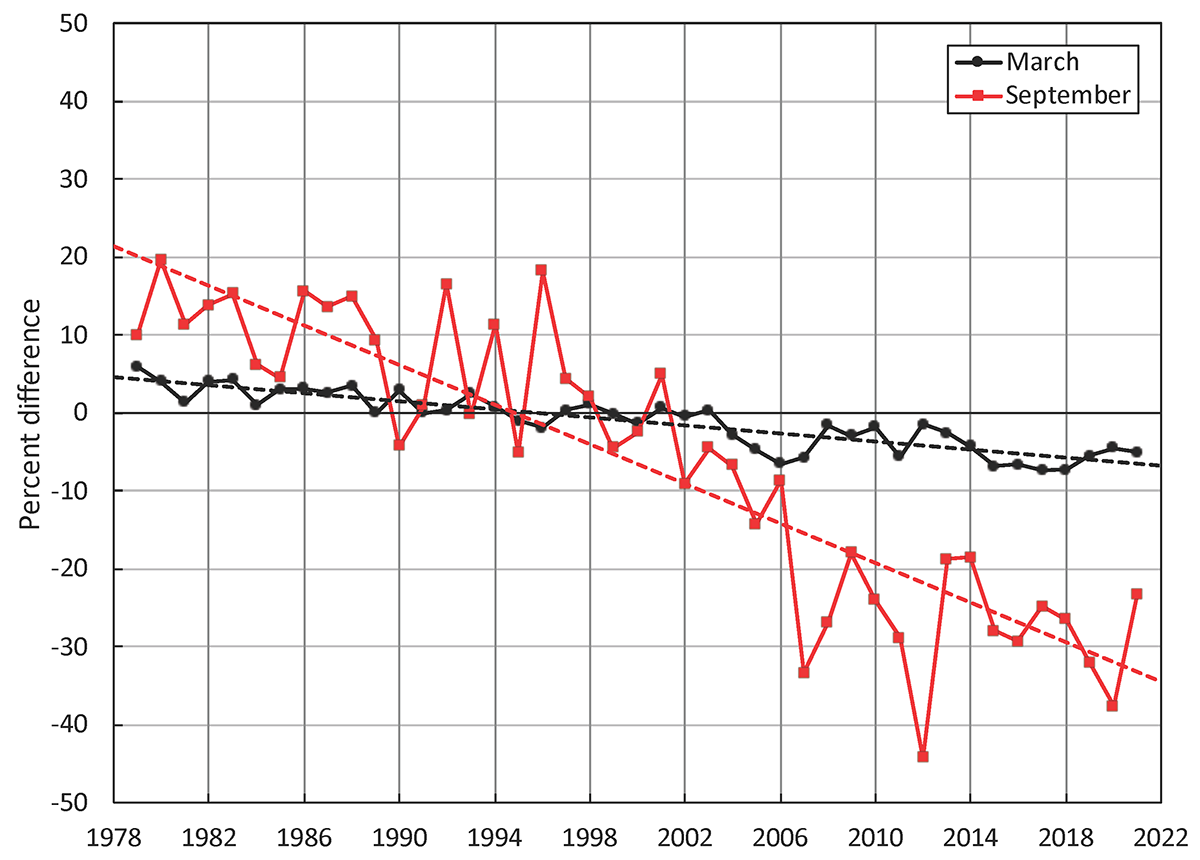

Since 1979 it has been possible to monitor sea ice by satellite. At present, We have 44 years of reliable information on the extent of the sea ice cover. The sea ice had continuously diminished and particularly since the end of the 1990s. Nevertheless, the winter trend is different from the summer trend.

In the video below we can see the long-term evolution of sea ice extent and temperatures in the Arctic

Anyhow, the warmest climatological period of the year just passed within the Arctic Circle, particularly closer to the North Pole. The year 2022 recorded mostly above-average temperatures, but in the end, it hasn’t been quite as anomalous as some recent years so far. This is especially true when looking at the Spring and Summer of 2022.

In the image above we can see the daily 2 meters temperature for the Arctic in 2022 averaged above 80°N. 1958-2021 mean is plotted in green while 2022 is highlighted in red. The image is available thanks to the Danish Meteorological.

In the last 40 years, the Arctic warmed definitely much faster than the rest of the world, something known as Arctic amplification. Several studies reported how the Arctic is warming either twice, or even three times as fast as the globe on average.

A new study showed how Arctic regions warmed nearly four times faster than the globe. Scientists compared the observed Arctic amplification ratio with the ratio simulated by state-of-the-art climate models and found that the observed four-fold warming ratio from 1979–2021 is an extremely rare occasion in climate model simulations.

The observed and replicated amplification ratios are more consistent with each other if calculated over a longer period. Such a result indicates how the recent four-fold Arctic warming ratio is either an extremely unlikely event, or the climate models systematically tend to underestimate the amplification.

Simply speaking, the present situation in the Arctic is definitely worse than what has been predicted by climate models. But why the Arctic is warming at an accelerated pace? This is mainly due to the so-called Arctic Amplification.

The image above available from the met office https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/cryosphere-oceans/sea-ice/index shows the ice-albedo feedback leading to amplification of warming in the Arctic.

Arctic Amplification refers to the enhancement of air temperature change near the ground over the Arctic relative to lower latitudes. These mechanisms include both local feedback and changes in poleward energy transport.

Temperature and sea ice-related feedbacks are especially important for Arctic Amplification since they are significantly more positive over the Arctic than at lower latitudes.

Changes in albedo from a frozen light sea surface to a free-of-ice and darker sea surface allow positive feedback affecting mean and extreme temperatures in the Arctic.

In the Image below by Zachari Labe, annual mean surface air temperature anomalies for the Arctic (67-90°N) and for the Global average (90°S-90°N) from 1950 to 2020. Data are presented for both global land and ocean only respectively in red and blue.

Linear trend lines (dashed) are also shown over the 1990 to 2020 period. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMPv4) is available from 1880 to 2020 at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/. The temperature rise in the Arctic is mostly influenced by the Arctic sea ice reduction, and not the other way around as one might think.

Like many other parts of the Earth’s climate, monitoring of Arctic sea ice makes use of numerous observational datasets using both in-situ and remote sensing methods.

Observations from in-situ measurements and satellites show a trend of a noteworthy decrease in the extent and volume of Arctic sea ice. As there is a lot of year-to-year variability in the weather, the mass balance in the Arctic tends to vary from one year to the other. It is useful to show again the image we already posted above.

https://arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card/Report-Card-2021/ArtMID/8022/ArticleID/945/Sea-Ice

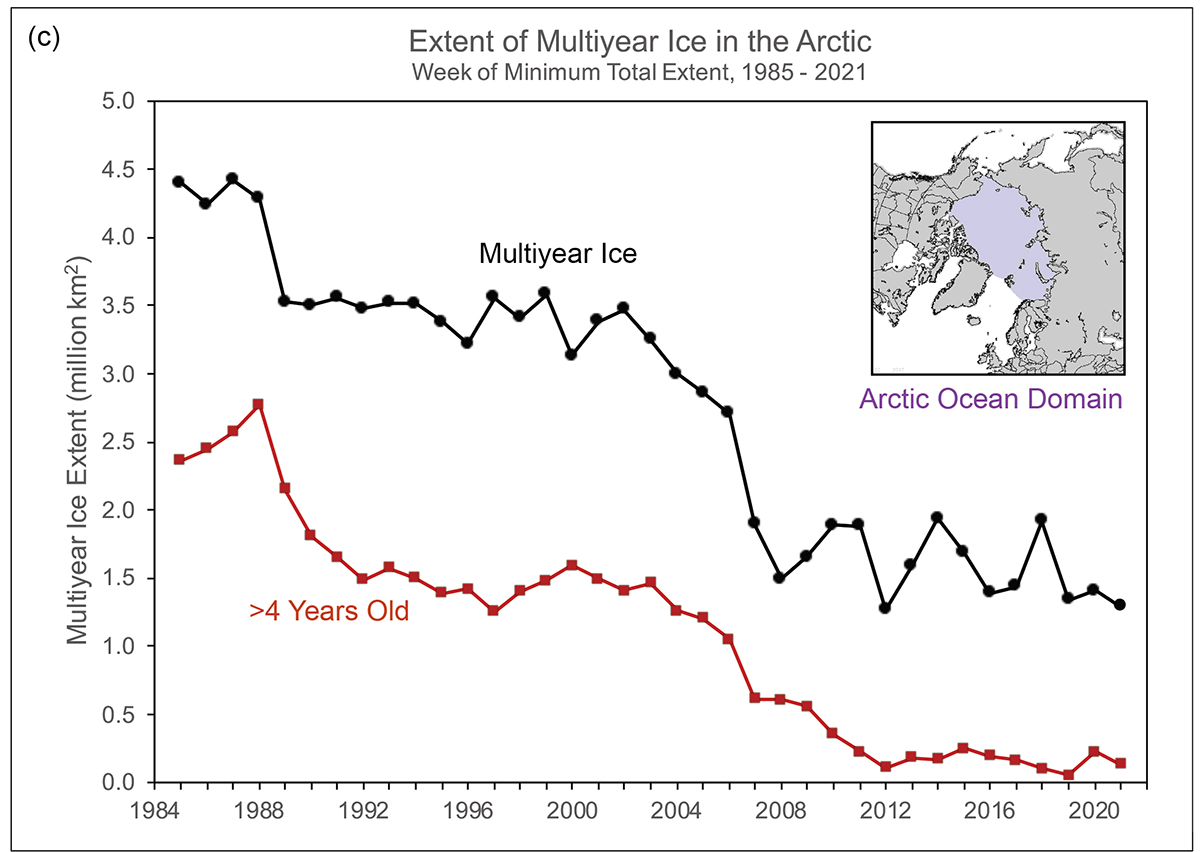

Monthly sea ice extent anomalies (solid lines) and linear trend lines (dashed lines) for March (black) and September (red) from 1979 to 2021 are shown in the image above. The anomalies are relative to the 1981 to 2010 average for each month.

An unusually warm summer might cause the ice to melt more than usual leading to a negative mass balance and, similarly, a cold summer or winter can cause the sea ice to grow leading to a positive mass balance.

The most dramatic indicator of a changing Arctic climate in recent years has been the summer minimum extent of Arctic sea ice in September as observed from space.

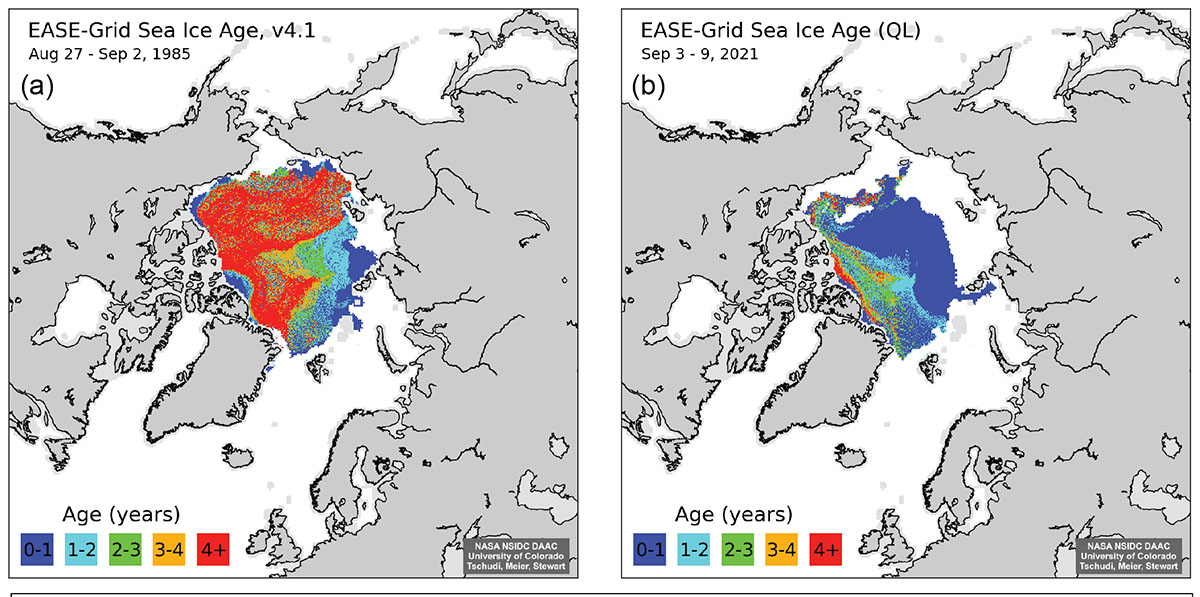

Sea ice drifts around the Arctic Ocean forced by winds and ocean currents and can thus grow and melt here and there. Age is a proxy for thickness as multiyear ice that survives one or more summer melt season grows thicker in the next winter.

If sea ice extent decreases, the ice age does the same. The September multiyear sea ice extent declined from 4.40 million square kilometers in 1985 to 1.29 million square kilometers in 2021.

Over the same period, the oldest ice (>4 years old) declined from 2.36 million square kilometers to 0.14 million square kilometers.

Sea ice age coverage for the week before the minimum total extent is shown in the map below thanks to the NOAA Arctic program

FORECAST OF SEPTEMBER SEA ICE EXTENT

The fast summer Artic sea ice retreat became an icon of climate change. lower summer sea ice cover comes with larger ice variability, posing great complications for planning and even threats to operations of commercial activities in the Arctic.

More importantly, the recent rapid decline of Arctic sea-ice extent and the projected continued decline in the future raise an important question as to the possible impacts of sea ice losses on the Northern Hemisphere weather and climate.

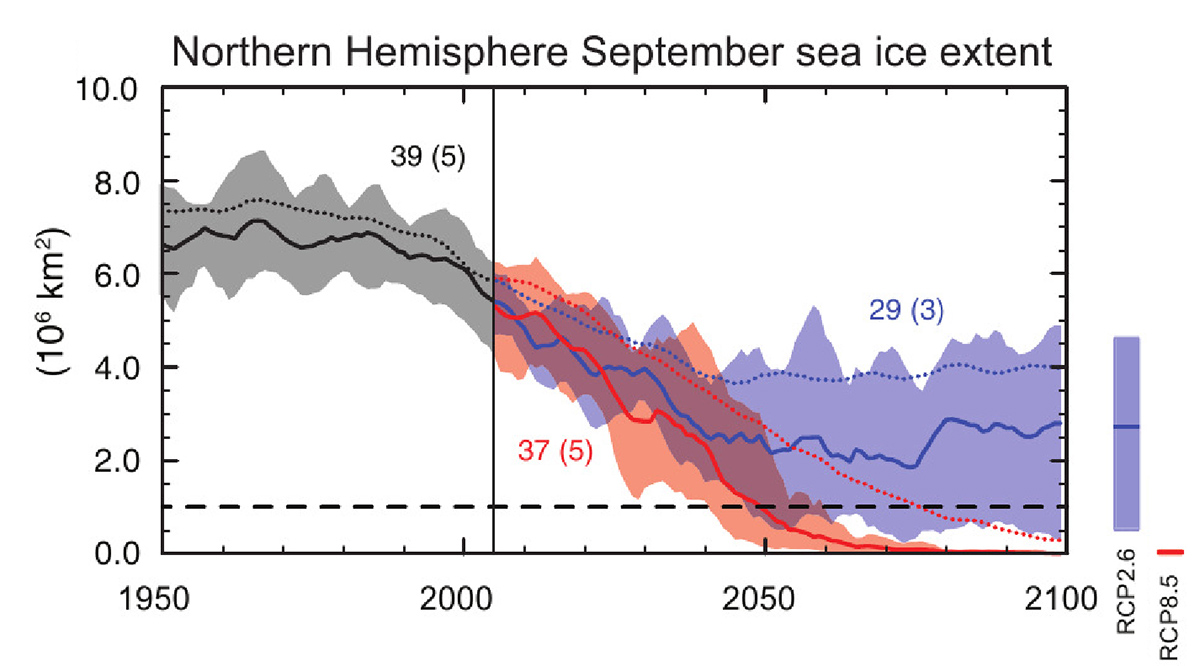

In the image below projections of September sea ice extent under the worse (RCP 8.5 business and usual) and best (RCP 2.6) possible scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions.

The international effort to provide expected September mean Arctic sea ice extent is currently undertaken by the Sea Ice Prediction center. The extent of the sea ice cover in the Arctic remains variable as synoptic weather conditions play a role in determining the growth and melt of sea ice and its movement within the Arctic basin.

During the first half of August, air temperature at the 925 hPa level (about 700 meters or 2,500 feet above the surface) was slightly warmer than average from the Beaufort Sea across the pole and towards the Kara and Barents Seas.

Over parts of the East Siberian and Laptev Seas as well as the southeastern Bering Sea temperatures were instead slightly below average.

Although air temperature in the central Arctic Ocean is moderately above average, it is actually near the freezing point and freeze-up is likely already happening at the surface near the pole. Present open water areas will likely be gone soon.

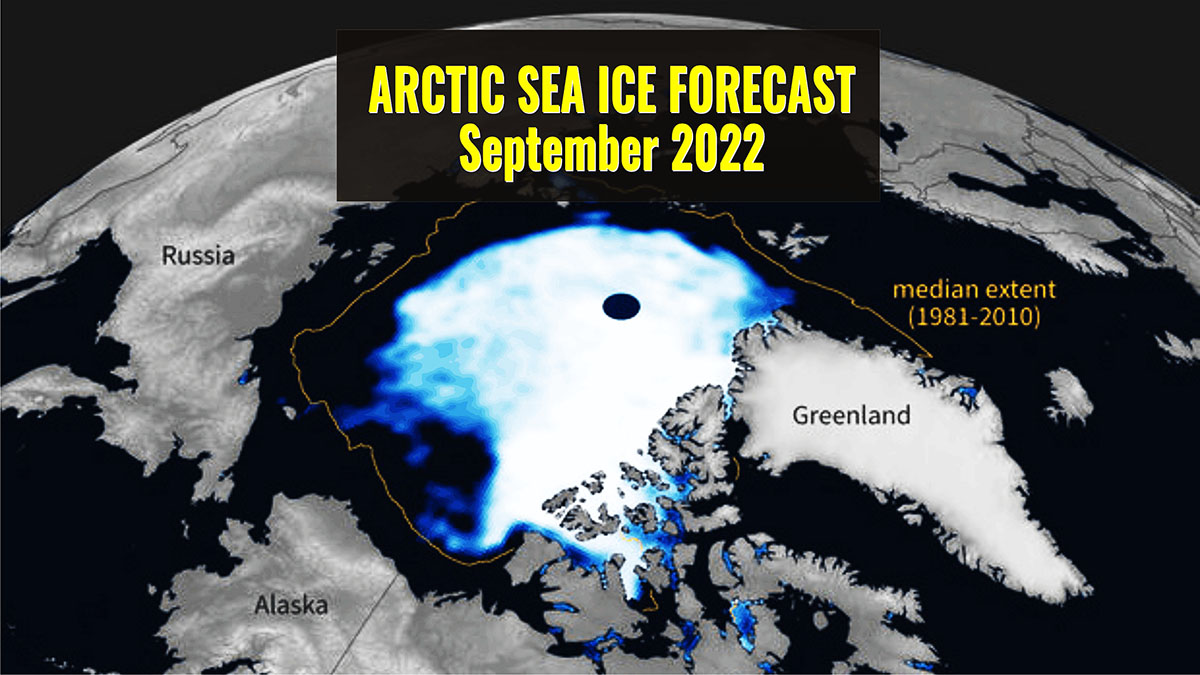

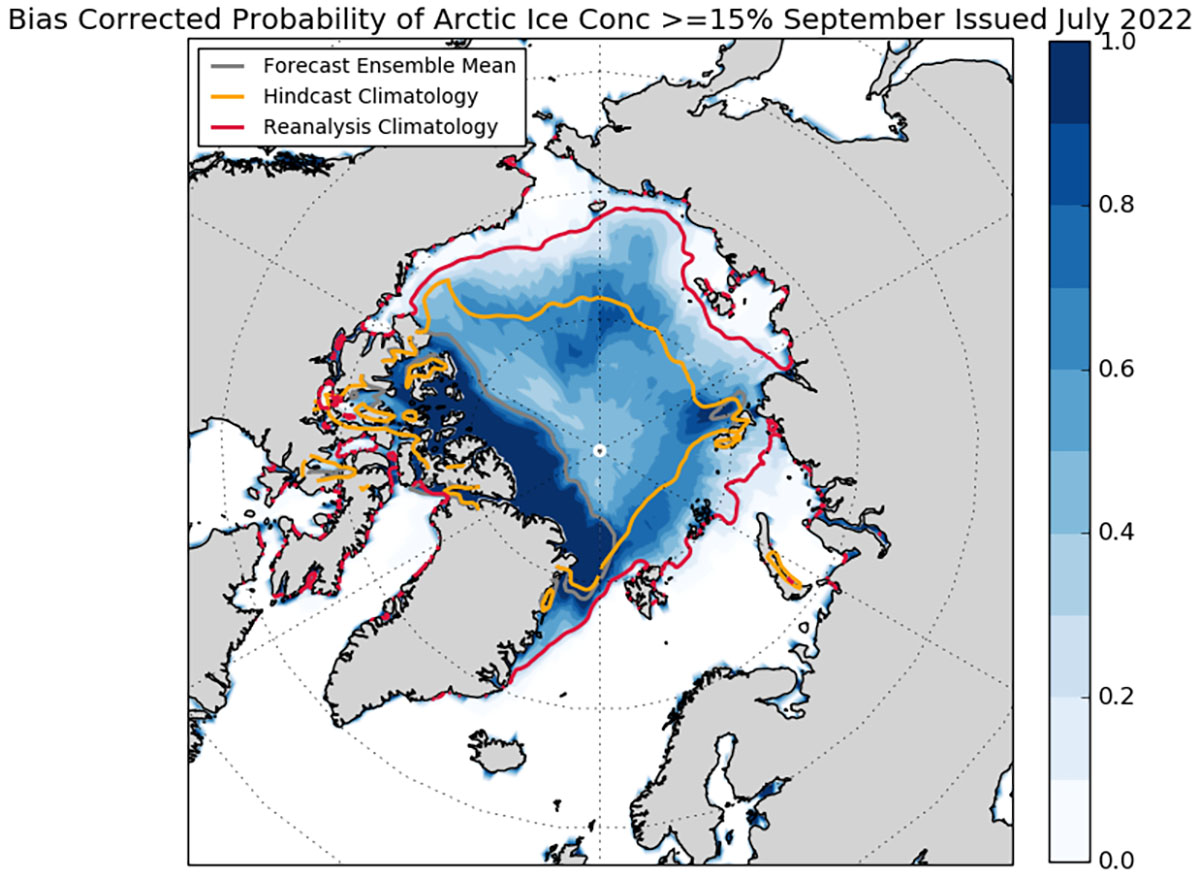

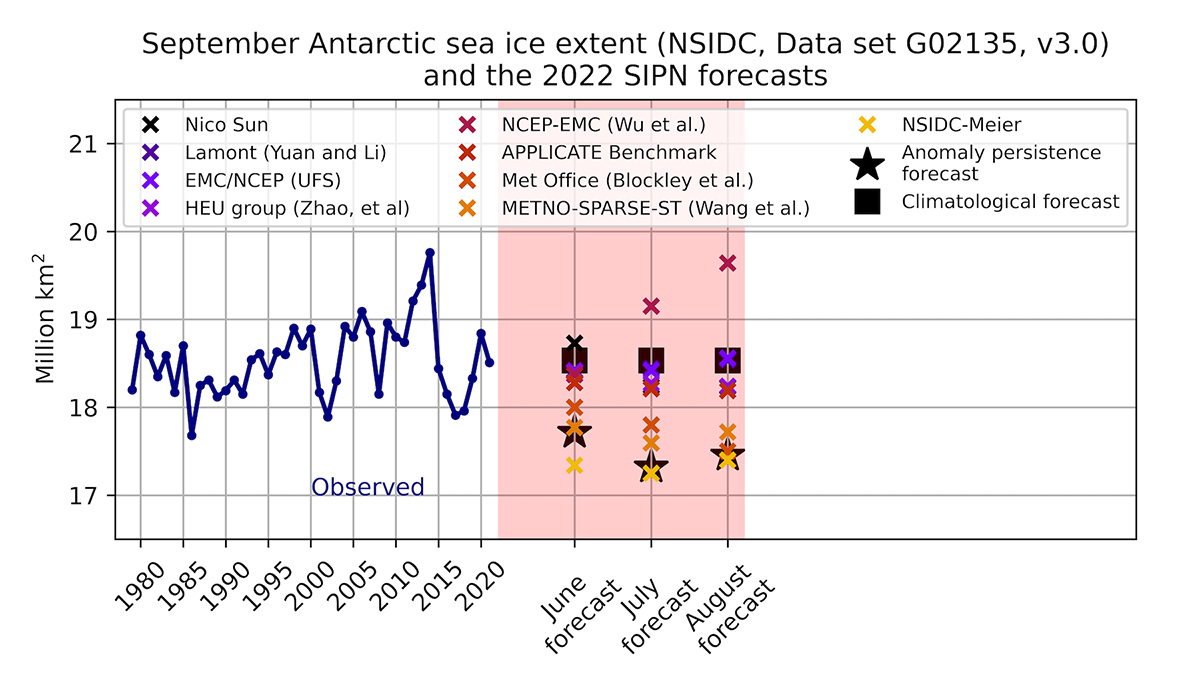

The 2022 August Sea Ice Outlook has been just released and the report is available online. The median August Outlook value for September 2022 pan-Arctic sea-ice extent is 4.83 million square kilometers with a higher probability to fall within the range of 4.6 to 5.0 million square kilometers.

This value is higher than what was forecasted in July (4.64 million square kilometers) and June (4.57 million square kilometers).

The August 2022 forecasts continue to predict Alaska sea-ice extent (Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas) greater than the 2007–2021 average of 0.40 million square kilometers. This August Outlook Report was developed by lead author Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and others.

The August Outlook is based on a total of 28 forecasts. As the 2022 season has progressed, the median SIO pan-Arctic September mean anomaly forecast has become more positive.

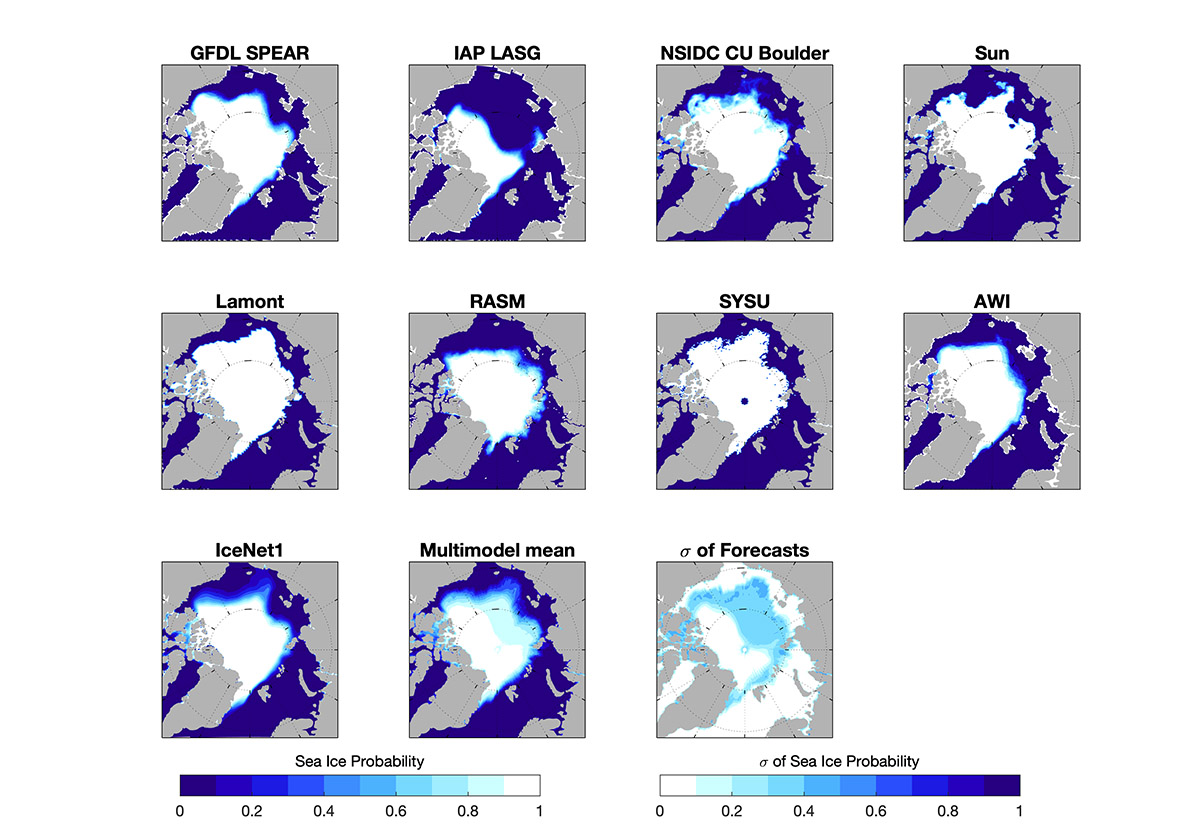

Nevertheless, sea ice probability shows a considerable model spread with some models forecasting very low sea ice probability while others very high throughout the Arctic ocean.

Regionally, all models show a rather good agreement in the European Arctic and especially in the east Greenland Sea and northern Barents and Kara seas as well as in the eastern Beaufort.

The main issue is represented by the sea ice cover forecast in the east Siberian sea. Here, the likelihood of survival of the area of sea ice that currently extends to the east Siberian coastline is the source of major error. Especially this area will play a crucial role in the generation of cold air masses on the Siberian planes. We will follow the situation very closely.

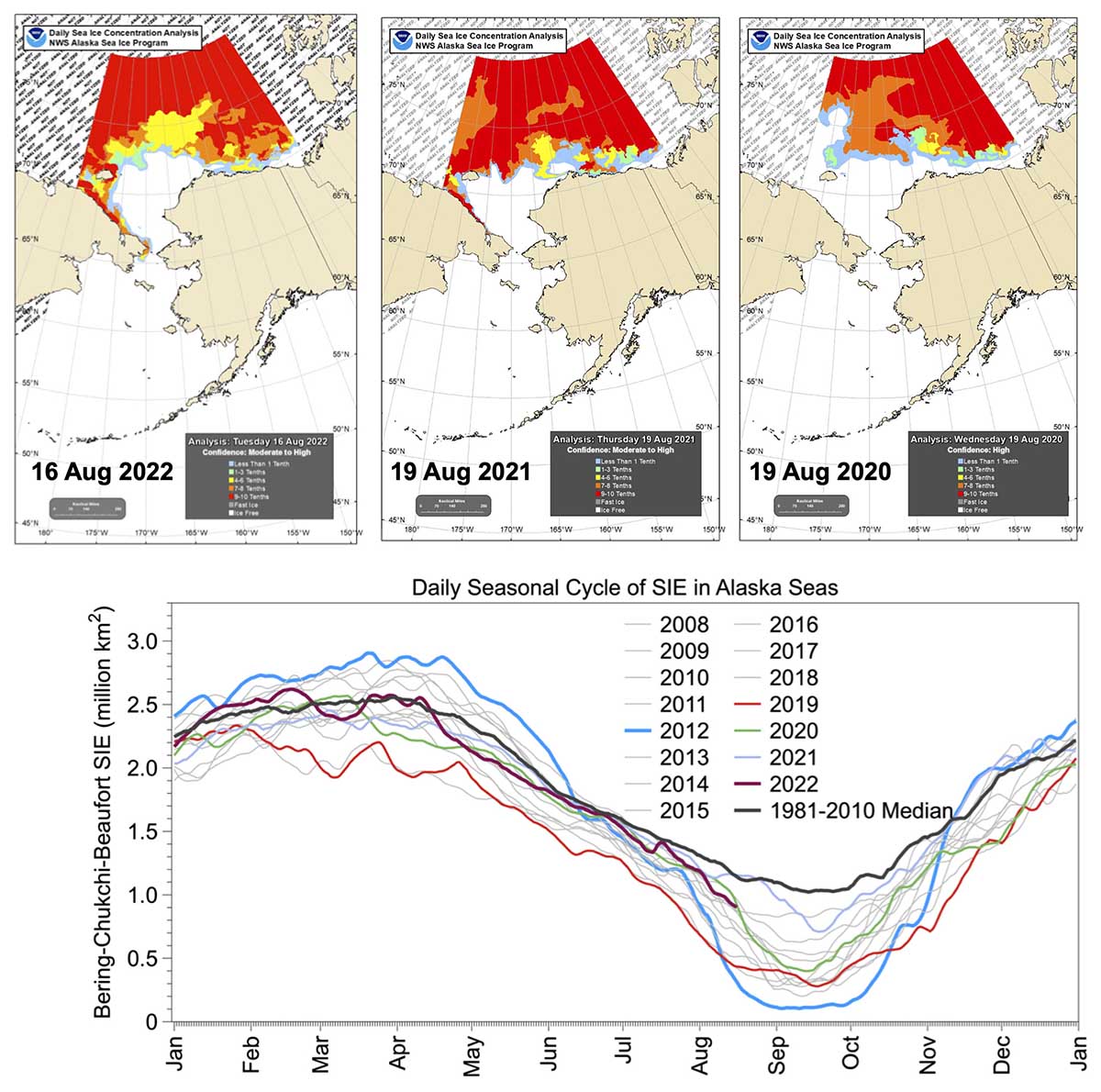

The multi-modal median for the August 2022 Sea Ice Outlook forecast for the Alaska seas is 0.67 million square kilometers and consists of eight contributions with values ranging from 0.46 to 1.01 million square kilometers.

To room these in a historical view, the September median sea-ice extent for the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas over 2007–2021 is above all observed values between 2015 and 2020.

As we mentioned above sea ice extent in the Alaska seas displays greater ice concentration. In the image below sea ice concentration from the National Weather Service Alaska Sea Ice Program for mid-August 2022, 2021, and 2020.

The image below we can see the observed mean September sea ice extent in the Alaska seas (blue line) and Sea Ice Outlook median August forecast (blue solid pentagon).

The 2022 August median forecast is shown by the blue open pentagon. A cubic fit is shown in black. Bottom: Expanded plot for 2016–2022 displays SIO median forecasts for June, July, and August for the Alaska Seas.

ANTARCTIC OUTLOOK

If in the Arctic we are approaching the annual sea ice minimum, on the other side of the globe, in Antarctica, the annual maximum is the next imminent target in September.

The Arctic and Antarctic are geographic opposites, and not just because they stand on opposite ends of the Earth’s globe. They also have opposite land-sea arrangements. In the Arctic, continents surround an ocean, while in Antarctica the continent is surrounded by oceans.

These differences in the arrangement of land and water contribute to differences in each polar region’s climate, oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns, and sea ice. As anticipated by previous forecasts, 2022 is predicted to be a low year and likely even a record one.

Almost all forecasts agree in predicting that the sea ice extent in September will be below normal. As a matter of fact, in February the record low sea ice extent was set and it is therefore extremely possible that the annual mean in 2022 will also reach record low values

In the image above time-series of observed September Antarctic sea-ice extent and for June through August 2022 individual model forecasts and climatological forecasts.

We will keep you updated on this and much more, so make sure to bookmark our page. Also, if you have seen this article in the Google App (Discover) feed or on social media, click the like button (♥) to see more of our forecasts and our latest articles on weather and nature in general.

SEE ALSO: